Herihor

| Herihor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Herihor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1080–1074 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Piankh? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Pinedjem I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Nodjmet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1074 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Concurrent with the 21st Dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

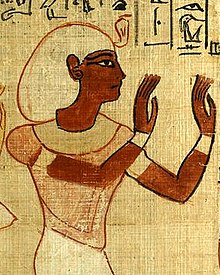

Herihor was an Egyptian army officer and High Priest of Amun at Thebes (1080 BC to 1074 BC) during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses XI.

Chronological and genealogical position

[edit]Traditionally his career was placed before that of the High Priest of Amun, Piankh, since it was believed that the latter was his son. However, this filiation was based on an incorrect reconstruction by Karl Richard Lepsius of a scene in the Temple of Khonsu. It is now believed that the partly preserved name of the son of Herihor depicted there was not [Pi]Ankh, but rather Ankh[ef(enmut)].[1]

Since then, de:Karl Jansen-Winkeln has argued that Piankh preceded rather than succeeded Herihor as High Priest at Thebes and that Herihor outlived Ramesses XI before being succeeded in this office by Pinedjem I, Piankh's son.[2] If Jansen-Winkeln is correct, Herihor would have served in office as High Priest, after succeeding Piankh, for longer than just 6 years, as is traditionally believed.

The following paragraphs contain several statements based on the traditional order (Herihor before Piankh) and therefore give only one possible reconstruction.

Life

[edit]While his origins are unknown, it is thought that his parents were Libyans.[3] Jansen-Winkeln's recent publication in Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache suggests that Piankh – originally thought to be Herihor's successor – was actually Herihor's predecessor.[4]

Herihor advanced through the ranks of the military during the reign of Ramesses XI. His wife Nodjmet, may have been Ramesses XI's daughter—and perhaps even Piankh's wife if Piankh was his predecessor as Jansen-Winkeln today hypothesizes.[5] At the decoration of the hypostyle hall walls of the temple of Khonsu at Karnak, Herihor served several years under king Ramesses XI since he is shown obediently performing his duties as chief priest under this sovereign.[6] But he assumed more and more titles, from high priest to vizier, before finally openly taking the royal title at Thebes, even if he still nominally recognised the authority of Ramesses XI, the actual king of Egypt. It is disputed today whether or not this 'royal phase' of Herihor's career began during or after Ramesses XI's lifetime.

Herihor never really held power outside the environs of Thebes, and Ramesses XI may have outlived him by two years although Jansen-Winkeln argues that Ramesses XI actually died first and only then did Herihor finally assume some form of royal status at Thebes and openly adopted royal titles—but only in a "half-hearted" manner according to Arno Egberts who has adopted Jansen-Winkeln's views here.[7] Herihor's usurpation of royal privileges is observed "in the decoration of the court of the Khonsu temple" but his royal datelines "betray nothing of the royal status he enjoyed according to the contemporary scenes and inscriptions of the court of the Khonsu temple."[7] While both Herihor and his wife Nodjmet were given royal cartouches in inscriptions on their funerary equipment, their 'kingship' was limited to a few relatively restricted areas of Thebes whereas Ramesses XI's name was still recorded in official administrative documents throughout the country.[8] During the Wehem Mesut era, the Theban high priest—Herihor—and Ramesses XI quietly agreed to accept the new political situation where the High Priest was unofficially as powerful as Pharaoh. The report of Wenamun (also known as Wen-Amon) was made in Year 5 of Herihor and Herihor is mentioned in several Year 5 and Year 6 mummy linen graffiti.

The de facto split between Ramesses XI and his 21st Dynasty successors with the High Priests of Amun at Thebes (referred to in Ancient Egyptian as Wehem Mesut or 'Renaissance') resulted in the unofficial political division of Egypt between Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, with the kings ruling Lower Egypt from Tanis. This division did not come to a complete end until the accession of the Libyan Dynasty 22 king Shoshenq I in 943 BC. Shoshenq was able to appoint his son Iuput to be the new High Priest of Amun at Thebes, thus exercising authority over all of ancient Egypt.

Herihor and the Nodjmet problem

[edit]It is beyond doubt that Herihor had a wife called Nodjmet. She has been attested in the Temple of Khonsu where she is depicted at the head of a procession of children of Herihor, and on Stela Leiden V 65, where she is depicted with Herihor, presented as High Priest without royal overtones, so apparently dating from quite early in his career.

Normally, she is identified with the mummy of a Nodjmet which was discovered in the Deir el-Bahari cache (TT320). With this mummy two Books of the Dead were found.[9]

One of these, Papyrus BM 10490, now in the British museum, belonged to "the King’s Mother Nodjmet, the daughter of the King's Mother Hrere". Whereas the name of Nodjmet was written in a cartouche, the name of Hrere was not. Since mostly this Nodjmet is seen as the wife of the High Priest Herihor, Herere’s title is often interpreted as "King's Mother-in-law",[10] although her title "who bore the Strong Bull" suggests that she actually must have given birth to a king.[11]

Ethiopian tradition

[edit]The 1922 regnal list of Ethiopia names Herihor, and his successors through Psusennes III, as part of the Semitic Ag'azyan Ethiopian dynasty,[12] and he is considered to have ruled Ethiopia for 16 years in addition to being de facto ruler in Egypt. This regnal list dated Herihor's reign to 1156-1140 BC, with dates following the Ethiopian Calendar.[12] According to Ethiopian historian Tekletsadiq Mekuria, Herihor's father was the former High Priest Amenhotep, and his mother was a daughter of Ramesses IV.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ The Epigraphic Survey, The Temple of Khonsu, I, (OIP 100), preface, x-xii.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln, Karl, "Das Ende des Neuen Reiches", Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache, (in German) 119 (1992), pp. 22-37.

- ^ Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul: The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt (British Museum Press, 1995), p. 124.

- ^ Karl Jansen-Winkeln, "Das Ende des Neuen Reiches", Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache, (in German) 119 (1992), pp. 22-37.

- ^ Jansen-Winkeln, pp. 22-37.

- ^ Egberts, Arno: "Hard Times: The Chronology of "The Report of Wenamun" Revised", Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache, 125 (1998), p. 96.

- ^ a b Egberts, p. 97.

- ^ Shaw & Nicholson, p. 125.

- ^ Kitchen, The Third Intermediate Period in Egypt (1100–650 BC), 2nd ed. (Warminster: Aris & Phillips Limited, 1986), pp. 42-45.

- ^ Kitchen, p. 44.

- ^ Wente, E., Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 26 (1967), pp. 173-174.

- ^ a b Rey, C.F., In the Country of the Blue Nile, 1927, p. 266.

- ^ Mekuria, Tekletsadiq: History of Nubia, 1959.

Further reading

[edit]- Lefebvre, M. Gustave, "Herihor, Vizir (Statue du Caire, no 42190)", ASAE, (in French) 26 (1926), pp. 63-68.

- Kees, Hermann: Die Hohenpriester des Amun von Karnak von Herihor bis zum Ende der Äthiopenzeit (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1964).

- Bonhême, Marie-Ange: "Hérihor fut-il effectivement roi?", BIFAO 79 (1979), pp. 267-283.

- Jansen-Winkeln, Karl, "Das Ende des Neuen Reiches", Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 119 (1992), 22-37

- Forbes, Dennis C., "King Herihor, the 'Renaissance' & the 21st Dynasty", KMT, 4-3 (1993), pp. 25-41.

- Goldberg, Jeremy: "Was Piankh The Son Of Herihor After All?" Göttinger Miszellen, 174 (2000), pp. 49-58.

- James, Peter & Morkot, Robert, "Herihor's Kingship and the High Priest Piankh", JEGH, 3.2 (2010), pp. 231-260.

- Haring, Ben, "Stela Leiden V 65 and Herihor's Damnatio Memoriae", Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur, 41 (2012), pp. 139-152.

- Steven R. W. Gregory, "Piankh and Herihor: Art, Ostraca, and Accession in Perspective", Birmingham Egyptology Journal 1 (2013) pp. 5-18.

- Thijs, Ad, "Nodjmet A, Daughter of Amenhotep, Wife of Piankh and Mother of Herihor", Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 140 (2013), pp. 54-69.

- Gregory, Steven R. W., Herihor in art and iconography: kingship and the gods in the ritual landscape of Late New Kingdom Thebes, (Golden House Publications, 2014)