Battle of al-Qadisiyyah

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2024) |

| Battle of al-Qādisiyyah | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Muslim conquest of Persia | |||||||||

Depiction of the battle from a manuscript of the Persian epic Shahnameh | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Rashidun Caliphate | Sasanian Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Sa`d ibn Abī Waqqās Khalid bin Arfatah[1] Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha Al-Qa'qa' ibn Amr al-Tamimi Asim ibn 'Amr al-Tamimi Abdullah ibn al-Mu'tam Shurahbil ibn Simt Zuhra ibn al-Hawiyya Jarir ibn Abd Allah al-Bajali Tulayha Amru bin Ma'adi Yakrib |

Rostam Farrokhzād † Bahman Jadhuyih † Hormuzan Jalinus †[2] Shahriyar bin Kanara †[3] Mihran Razi Piruz Khosrow Kanadbak Grigor II Novirak †[4] Tiruyih Mushegh III †[4] Javanshir Nakhiragan | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Rashidun army | Sasanian army | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 30,000[5] | Unknown[a] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Heavy[7] | Heavy[7] | ||||||||

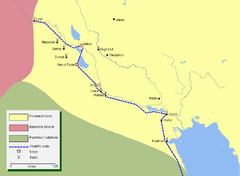

Location within modern-day Iraq | |||||||||

The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah[b] (Arabic: مَعْرَكَة ٱلْقَادِسِيَّة, romanized: Maʿrakah al-Qādisīyah; Persian: نبرد قادسیه, romanized: Nabard-e Qâdisiyeh) was an armed conflict which took place in 636 CE between the Rashidun Caliphate and the Sasanian Empire. It occurred during the early Muslim conquests and marked a decisive victory for the Rashidun army during the Muslim conquest of Persia.

The Rashidun offensive at Qadisiyyah is believed to have taken place in November of 636. The leader of the Sasanian army at the time, Rostam Farrokhzad, died in uncertain circumstances during the battle. The subsequent collapse of the Sasanian army in the region led to a decisive Arab victory over Sasanian power, and the incorporation of territory that comprises modern-day Iraq into the Rashidun Caliphate.[8]

Arab successes at Qadisiyyah were key to the later conquest of the Sasanian province of Asoristan, and were followed by major engagements at Jalula and Nahavand. The battle allegedly saw the establishment of an alliance between the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, with claims that the Byzantine emperor Heraclius married off his granddaughter Manyanh to the Sasanian king Yazdegerd III to symbolize the alliance.[citation needed]

Background

After the assassination of Byzantine emperor Maurice by pretender Emperor Phocas, the shah of the Sasanian Empire, Khosrow II, declared war on the Byzantine empire, starting the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. Forces of the Sasanian Empire invaded and captured Syria, Egypt, and Anatolia, and carried the True Cross away in triumph.

After being deposed in 610, Phocas was succeeded by Heraclius, who led the Byzantines in a war of reconquest, successfully regaining territory lost to the Sasanians. Heraclius defeated a small Persian army at the final Battle of Nineveh and advanced towards Ctesiphon.

During this period, Khosrow II was overthrown and executed by one of his sons, Kavadh II. Kavadh subsequently made peace with the Byzantines and returned all captured territories as well as the True Cross. The Göktürks, attacking the north of Persia with a massive army during peace proceedings, were ordered by Heraclius to retreat after the signing of the pact with Kavadh.

Internal conflicts of succession

After a few short months of reign, Kavadh II suddenly died of the plague; the ensuing power vacuum quickly led to a civil war. Ardashir III (c. 621–630), son of Kavadh II, was raised to the throne at age seven, but was killed 18 months later by his general, Shahrbaraz, who then declared himself ruler. In 613 and 614, Shahrbaraz took both Damascus and Jerusalem from the Byzantine Empire, respectively.

On 9 June 629, Shahrbaraz was killed during an invasion from Armenia by a Khazar–Göktürk force under Chorpan Tarkhan. He was succeeded by Boran, the daughter of Khosrow II. She was the 26th sovereign monarch of Persia, ruling from 17 June 629 to 16 June 630, and was one of only two women to sit on the Sasanian throne, the other being her sister Azarmidokht. She was made empress regnant on the understanding that she would vacate the throne upon Yazdegerd III (632-651), the son of Shahriyar and Grandson of Khosrow II, attaining majority.

Boran attempted to bring stability to the empire by implementing justice, reconstructing and fixing infrastructure, lowering taxes, minting coins, and signing a peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire. She also appointed Rostam Farrokhzād as the commander-in-chief of the Persian army.

However, Boran was largely unsuccessful in restoring the power to the central authority, which had been weakened considerably by civil wars, and either resigned or was murdered soon after ascending to the throne. She was replaced by her sister Azarmidokht, who in turn was replaced by Hormizd VI, a noble of the Persian court.

After five years of internal power struggle, Yazdegerd III, grandson of Khosrow II, became emperor at the age of eight in 632.[9] The real power of the Persian state was held in the hands of generals Rostam Farrokhzād and Piruz Khosrow (also known as Piruzan).

The coronation of Yazdegerd III infused new life into the Sasanian Empire.

Rise of the Caliphate and invasion of Iraq

After the death of Muhammad, Abu Bakr established control over Arabia through the Ridda Wars and then launched campaigns against the remaining territories of Syria and Palestine. He triggered the chain of events that would in a few decades form one of the largest empires the world had ever seen.[10] This put the nascent Islamic empire on a collision course with the Byzantine and Sassanid empires, which were the two superpowers of the time. The wars soon became a matter of conquest that would eventually result in the demise of the Sassanid empire and the annexation of all of the Byzantine Empire's southern and eastern territories. To make victory certain, Abu Bakr decided that the invading army would consist entirely of volunteers and would be commanded by his best general, Khalid ibn al-Walid. Khalid won quick victories in four consecutive battles: the Battle of Chains, fought in April 633; the Battle of River, fought in the third week of April 633; the Battle of Walaja, fought in May 633; followed by the decisive Battle of Ullais, fought in mid-May, 633. By now the Persian Empire was struggling, and in the last week of May 633, the capital city of Iraq, Al-Hirah, fell to the Muslims after the Battle of Hira.[10] Thereafter, the Siege of Al-Anbar during June–July 633 resulted in the surrender of the city after strong resistance. Khalid then moved towards the south and conquered the city of Ein ul Tamr after the Battle of Ayn al-Tamr in the final week of July 633. In November 633, the Persian counterattack was repulsed by Khalid. In December 633, Muslim forces reached the border city of Firaz, where Khalid defeated the combined Sassanid, Byzantine, and Christian Arab armies in the Battle of Firaz. This was the last battle in the conquest of Iraq.

By this time, except for Ctesiphon, Khalid had captured all of Iraq. However, circumstances changed on the western front. The Byzantine army soon came into direct conflict in Syria and Palestine, and Khalid was sent with half of his army to deal with this new development. Soon after, Caliph Abu Bakr died in August 634 and was succeeded by Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattāb. Muslim forces in Iraq were too few in number to control the region. After the devastating invasion by Khalid, the Persians took time to recover; political instability was at its peak at Ctesiphon. Once the Persians recovered, they concentrated more troops and mounted a counterattack. Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha, who was now commander-in-chief of the Muslim forces in Iraq, pulled his troops back from all outposts and evacuated Al-Hirah. He then retreated to the region near the Arabian Desert.[10] Meanwhile, Umar sent reinforcements from Madinah under the command of Abu Ubaid. The reinforcements reached Iraq in October 634, and Abu Ubaid assumed the command of the army and defeated the Sassanids at the Battle of Namaraq near modern-day Kufa. Then, in the Battle of Kaskar, he recaptured Hira.

The Persians launched another counterattack and defeated the Muslims at Battle of the Bridge, which killed Abu Ubaid, and the Muslims suffered heavy losses. Muthanna then assumed command of the army and withdrew the remnant of his forces, about 3000 strong, across the Euphrates. The Persian commander Bahman (also known as Dhu al-Hajib) was committed to driving the Muslims away from Persian soil but was restrained from pursuing the defeated Muslims after being called back by Rustum to Ctesiphon, to help in putting down the revolt against him. Muthanna retreated near the frontier of Arabia and called for reinforcements. After getting sufficient reinforcements, he re-entered the fray and camped at the western bank of the Euphrates, where a Persian force intercepted him and was defeated.

Persian counterattack

After Khalid left Iraq for Syria, Suwad, the fertile area between the Euphrates and the Tigris, remained unstable. Sometimes it was occupied by the Persians and sometimes by the Muslims. This "tit-for-tat" struggle continued until emperor Yazdegerd III consolidated his power and sought an alliance with Heraclius in 635 in an effort to prepare for a massive counterattack. Heraclius married his granddaughter, Manyanh, to Yazdegerd III, in accordance with Roman tradition to seal an alliance. Heraclius then prepared for a major offensive in the Levant. Meanwhile, Yazdegerd ordered a concentration of massive armies to reclaim Iraq for good. This was supposed to be a well-coordinated attack by both emperors to annihilate the power of their common enemy, Caliph Umar.

When Heraclius launched his offensive in May 636, Yazdegerd could not coordinate on time, so the plan was not carried out as planned. Meanwhile, Umar allegedly had knowledge of this alliance and devised his own plan to counteract it. He wanted to finish the Byzantines first, and later deal with the Persians separately. Accordingly, he sent 6,000 soldiers as reinforcements to his army in Yarmouk who were facing off the Byzantine army. Simultaneously, Umar engaged Yazdegerd III, ordering Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas to enter in peace negotiations with him by inviting him to convert to Islam.[c] Heraclius, fearing the above-mentioned scenario had instructed his general Vahan not to engage in battle with Muslims and await his orders. However, Vahan, witnessing fresh reinforcements for the Muslims arriving daily from Madinah, felt compelled to attack the Muslim forces before they got too strong. Heraclius's imperial army was annihilated at Battle of Yarmouk in August 636, three months before the battle of Qadisiyyah, therefore ending the Roman Emperor's offensive in the west. Undeterred, Yazdegerd continued to execute his plan of attack and concentrated armies near his capital Ctesiphon. A large force was put under the control of veteran general Rostam and was cantoned at Valashabad near Ctesiphon. Receiving news of preparations for a massive counterattack, Umar ordered Muthana to abandon Iraq and retreat to the edge of the Arabian Desert. The Iraqi campaign would be addressed at a later date.

Muslim battle preparation

Caliph Umar started raising new armies from throughout Arabia with the intention of re-invading Iraq. Umar appointed Sa'd ibn Abī Waqqās, an important member of the Quraysh tribe as commander of this army. In May 636, Sa'd was instructed to march to Northern Arabia with a contingent of 4,000 men from his camp at Sisra (near Madinah) and take over command of the Muslim army, and immediately march onward to Iraq. Because of his inexperience as a general, he was instructed by Caliph Umar to seek the advice of experienced commanders before making critical decisions. Umar sent orders to him to halt at al-Qadisiyyah, a small town 30 miles from Kufah.

Umar continued to remotely issue strategic orders and commands to his army throughout the campaign. Due to a shortage of manpower, Umar decided to lift the ban on the ex-apostate tribes of Arabia from participating in state affairs. The army raised was not professional but a volunteer force composed of newly recruited contingents from all over Arabia. After a decisive victory against the Byzantine army at the Yarmouk, Umar sent immediate orders to Abu Ubaidah to send a contingent of veterans to Iraq. A force of 5,000 veterans of Yarmouk was also sent to Qadisiyyah, arriving on the second day of the battle there. This proved to be a major turning point and a major morale booster for the Muslim army. The battle of Qadissiyyah was fought predominantly between Umar and Rostam, rather than between Sa'd and Rostam. Coincidentally, the bulk of the Sassanid army was also made up of new recruits, since the bulk of the regular Sassanid forces was destroyed during the Battles of Walaja and Ullais.

Battlefield

Qadisiyyah was a small town on the west bank of the river Ateeq, a branch of the Euphrates. Al-Hira, the ancient capital of Lakhmid Dynasty, was about thirty miles west. According to present-day geography, it is situated in the southwest of al-Hillah and Kufah in Iraq.

Troop deployment

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2013) |

Modern estimates suggest that the size of the Sassanid forces was about 30,000 strong and that of the Muslims was around 30,000 strong after being reinforced by the Syrian contingent on the second day of the battle. These figures come from studying the logistical capabilities of the combatants, the sustainability of their respective bases of operations, and the overall manpower constraints affecting the Sassanids and Muslims. Most scholars, however, agree that the Sassanid army and their allies outnumbered the Muslim Arabs by a sizable margin.

Sassanid Persia

The Persian army reached Qadisiyyah in July 636 and established their highly fortified camps on the eastern bank of the Ateeq river. There was a bridge over the Ateeq river, the only crossing to the main Sassanid camps, although they had boats available in reserve to cross the river.

The Sassanid Persian army, about 60,000 strong, fell into three main categories, infantry, heavy cavalry, and the Elephant corps. The Elephant corps was also known as the Indian corps, for the elephants were trained and brought from Persian provinces in India. On 16 November 636, the Sassanid army crossed over the west bank of Ateeq, and Rostam deployed his 45,000 infantry in four divisions, each about 150 meters apart from the other. 15,000 cavalry were divided among four divisions to be used as a reserve for counter-attack and offensives. At Qadisiyyah, about 33 elephants were present, eight with each of the four divisions of the army. The battle front was about 4 km long. The Sassanid Persians' right wing was commanded by Hormuzan, the right centre by Jalinus, the rear guard by Piruzan, and the left wing by Mihran. Rostam himself was stationed at an elevated seat, shaded by a canopy, near the west bank of the river and behind the right centre, where he enjoyed a wide view of the battlefield. By his side waved the Derafsh-e-Kāveyān (in Persian: درفش کاویان, the 'flag of Kāveh'), the standard of the Sassanid Persians. Rostam placed men at certain intervals between the battlefield and the Sassanid capital, Ctesiphon, to transmit information.

Rashidun

In July 636, the main Muslim army marched from Sharaf to Qadisiyyah. After establishing camp, organizing defences, and securing river heads, Sa'd sent parties inside Suwad to conduct raids. Sa'd was continuously in contact with Caliph Umar, to whom he sent a detailed report of the geographical features of the land where the Muslims encamped and the land between Qadisiyyah, Madinah, and the region where the Persians were concentrating their forces.

The Muslim army at this point was about 30,000 strong, including 7,000 cavalry. Its strength rose to 36,000 members once it was reinforced by the contingent from Syria and by local Arab allies. Sa'd developed sciatica, and had boils all over his body. He took a seat in the old royal palace at Qadisiyyah from where he directed the war operations and had a good view of the battlefield. He appointed as his deputy Khalid ibn Urfuta,[1] who carried out his instructions to the battlefield through the chains of messengers. The Rashidun infantry was deployed in four corps, each with its own cavalry regiment stationed at the rear for counterattacks. Each corps was positioned about 150 meters from the other. The army was formed on a tribal and clan basis so that every man fought next to well-known comrades and so that tribes were held accountable for any weakness.

Weapons

The Muslim forces wore gilded helmets similar to the silver helmets of the Sassanid soldiers. Chain Mail was commonly used to protect the face, neck, and cheeks, either as an aventail from the helmet or as a mail coif. Heavy leather sandals, as well as Roman-type sandal boots, were also typical of the early Muslim soldiers. Armor included hardened leather scale or lamellar armour and mail. The infantry was more heavily armoured than the cavalry. Hauberks and large wooden or wickerwork shields were used as well as long-shafted spears. Infantry spears were about 2.5 meters long and those of the cavalry were up to 5.5 meters long.

The swords used were similar to that of the Roman gladius and the Sassanid long sword. Both were worn and hung from a baldric. Bows were about two meters long when un-braced, about the same size as the famous English longbow, with a maximum range of about 150 meters. Muslim archers proved very effective against the opposing cavalry. The Rashidun troops at the Sassanid Persian front were lightly armoured compared to those deployed at the Byzantine front.

Battle

The Arabs had been camped at al-Qadisiyyah with 30,000 men since July 636. Umar ordered Sa'd to send emissaries to Yazdegerd III and the general of the Sasanian army, Rostam Farrokhzad, inviting them to convert to Islam. For the next three months, negotiations between the Arabs and Persians continued. On Caliph Umar's instructions, Saad sent an embassy to the court of Persia with instructions to convert the Sassanid emperor to Islam or to get him to agree to pay the jizyah. An-Numan ibn Muqarrin led the Muslim emissary to Ctesiphon and met Sasanian Emperor Yazdgerd III, but the mission failed.

During one meeting, Yazdgerd III, intent on humiliating the Arabs, ordered his servants to place a basket full of earth on the head of Asim ibn 'Amr al-Tamimi, a member of the emissary. The optimistic Arab ambassador interpreted this gesture with the following words: "Congratulations! The enemy has voluntarily surrendered its territory to us," (referring to the earth in the basket). Rustam, the Persian general, held a view similar to Asim ibn 'Amr. He allegedly rebuked Yazdgerd III for the basket of the earth because it signified that the Persians voluntarily surrendered their land to the Muslims. Yazdgerd III, upon hearing this, ordered soldiers to pursue the Muslim emissaries and retrieve the basket. However, the emissaries were already at their base camp at that point.

As tensions eased on the Syrian front, Caliph Umar instructed that negotiations be halted. This was an open signal to the Persians to prepare for battle. Rostam Farrokhzād, who was at Valashabad, broke camp for Qadisiyyah. He was inclined, however, to avoid fighting and once more opened peace negotiations. Sa'd sent Rabi bin Amir and later Mughirah bin Zurarah to hold talks. Rostam tried to incite Arabs to choose a peaceful outcome: "You are neighbours. Some of you were in our land and we were considerate of them and protected them from harm. We helped them in all manners. They brought their herd to graze in our pastures. We gave them foodstuff from our land. We let them trade in our land. Their livelihood was in good order [...] When there was a drought in your land and you asked us for help, we sent you dates and barley. I know that you are here because you are poor. I will order that your commander receives clothing and a horse with 1,000 dirhams and that each of you receive a load of dates and two sets of clothing so that you leave our land because I don't want to take you prisoner or kill you." But the emissaries insisted that Persians had to choose between becoming Muslim, paying Jizyah or making war. After the negotiations fell through, both sides prepared for battle.

Day 1

On 16 November 636, an intervening canal was choked up and converted into a road on Rostam's orders and before dawn, the entire Persian army crossed the canal. Rostam now armed himself with a double set of complete armour and requisite weapons. Both armies stood face to face about 500 meters apart. The Rashidun army was deployed facing northeast, while the Sassanid army was deployed facing southwest and had the river at its rear. Just before the battle started, Sa'd sought to encourage the soldiers: "This is your heritage, promised to you by your God. He made it available to you 3 years ago and you have been profiting from it until now, capturing, ransoming and killing its people." Asim ibn 'Amr told the riders: "You are superior to them and God is with you. If you are persistent and strike in the proper way, their riches, women and children will be yours."

The battle began with personal duels; Muslim Mubarizun stepped forward and many were slain on both sides. Muslim chronicles record several heroic duels between the Sassanid and Muslim champions. The purpose of these duels was to lower the morale of the opposing army by killing as many champions as possible. Having lost several in duels, Rostam began the battle by ordering his left wing to attack the Muslims' right wing.

The Persian attack began with heavy showers of arrows, which caused considerable damage to the Muslims' right wing. Elephants led the charge from the Persian side. Abdullah ibn Al-Mutim, the Muslim commander of the right-wing, ordered Jareer ibn Abdullah (cavalry commander of the right-wing) to deal with the Sassanid elephants. However, Jareer's cavalry was stopped by the Sassanid heavy cavalry. The elephants continued to advance, and the Muslim infantry began to fall back.

Saad sent orders to Al-Ash'ath ibn Qays, commander of the centre-right cavalry to check the Sassanid cavalry advance. Al-Ash'ath then led a cavalry regiment that reinforced the right wing cavalry and launched a counterattack at the flank of the Sassanid left wing. Meanwhile, Sa'd sent orders to Zuhra ibn Al-Hawiyya, commander of the Muslim right centre, to dispatch an infantry regiment to reinforce the infantry of the right wing. An infantry regiment was sent under Hammal ibn Malik that helped the right-wing infantry launch a counterattack against the Sassanids. The Sassanid left wing retreated under the frontal attack by the infantry of the Muslims' right-wing reinforced by infantry regiments from the right centre and a flanking attack by the Muslim cavalry reinforced by a cavalry regiment from the right centre.

With his initial attacks repulsed, Rostam ordered his right centre and right-wing to advance against the Muslim cavalry. The Muslim left wing and left centre were first subjected to intense archery, followed by a charge of the Sassanid right wing and right centre. Once again, the Elephant corps led the charge. The Muslim cavalry on the left wing and left centre, already in panic due to the charge of the elephants, were driven back by the combined charge of the Sassanid heavy cavalry and the elephants.

Sa'd sent word to Asim ibn 'Amr, commander of the left centre, to overpower the elephants. Asim's strategy was to overcome the archers on the elephants and cut the girths of the saddles. Asim ordered his archers to kill the men on elephants and ordered the infantry to cut the girths of the saddles. The tactic worked, and as the Persians retired the elephants, the Muslims counterattacked. The Sassanid army's centre right retreated followed by the retreat of the entire right wing. By afternoon, the Persian attacks on the Muslim left wing and left centre were also beaten back. Saad, in order to exploit this opportunity, ordered yet another counterattack. The Muslim cavalry then charged from the flanks with full force, a tactic known as Karr wa farr. The Muslim attacks were eventually repulsed by Rostam, who plunged into the fray personally and is said to have received several wounds. The fighting ended at dusk. The battle was inconclusive, with considerable losses on both sides.

In the Muslim chronicles, the first day of the battle of Qadisiyyah is known as Yawm al-Armath (يوم أرماث) or "The Day of Disorder".

Day 2

On 17 November, like the previous day, Sa'd decided to start the day with the Mubarizuns to inflict maximum morale damage on the Persians. At noon, while these duels were still going on, reinforcements from Syria arrived for the Muslim army. First, an advance guard under Al-Qaqa ibn Amr al-Tamimi arrived, followed by the main army under its commander Hashim ibn Utbah, nephew of Sa'd. Qa’qa divided his advance guard into several small groups and instructed them to reach the battlefield one after the other, giving the impression that a very large contingent of reinforcements had arrived. This strategy had a very demoralizing effect on the Persian army.

On this day, Qa’qa is said to have killed the Persian general Bahman, who had earlier commanded the Sassanid army at the Battle of Bridge. As there were no elephants in the Sassanid fighting force that day, Sa'd sought to exploit this opportunity to gain any breakthrough if possible, so he ordered a general attack. All four Muslim corps surged forward, but the Sassanids stood firm and repulsed repeated attacks. During these charges, Qa’qa resorted to the ingenious device of camouflaging camels to look like strange monsters. These monsters moved to the Sassanid front; seeing them, the Sassanid horses turned and bolted. The disorganization of the Sassanid cavalry left their left center infantry vulnerable. Sa'd ordered the Muslims to intensify the attack. Qa’qa ibn Amr, now acting as the field commander of the Muslim army, planned to kill Rostam and led a group of Mubarizuns, from his Syrian contingent who were also veterans of the Battle of Yarmouk, through the Sassanids' right centre towards Rostam's headquarters. Rostam once again personally led a counterattack against the Muslims, but no breakthrough could be achieved. At dusk, the two armies pulled back to their camps.

Day 3

On 18 November, Rostam wanted a quick victory, before more Muslim reinforcements could arrive. The Elephant corps was once again in front of the Sassanid army, giving him the advantage. Pressing this advantage, Rostam ordered a general attack along the Muslim front, using his entire force. All four Sassanid corps moved forward and struck the Muslims on their front. The Persian attack began with the customary volley of arrows and projectiles. The Muslims sustained heavy losses before their archers retaliated. The Persian elephant corps once again led the charge, supported by their infantry and cavalry. At the approach of the Sassanid elephants, the Muslim riders once again became unnerved, leading to confusion in the Muslim ranks. The Sassanids pressed the attack, and the Muslims fell back.

Through the gaps that had appeared in the foe's ranks because of the Sassanid advance, Rostam sent a cavalry regiment to capture the old palace where Sa'ad was stationed. Rostam's strategy was that the Muslim Commander-in-Chief had to be killed or taken captive to demoralize the Muslims. However, a strong cavalry contingent of Muslims rushed to the spot and drove away the Sassanid cavalry.

Sa'd determined that there was only one way to win the battle; to destroy the Sassanid elephant corps that was causing great havoc among the Muslim ranks. He issued orders that the elephants should be overpowered by blinding them and severing their trunks. After a long struggle, the Muslims finally succeeded in mutilating the elephants sufficiently to be driven off. The frightened elephant corps rushed through the Sassanid ranks and made for the river. By noon no elephants were left on the battlefield. The flight of the elephants caused considerable confusion in the Sassanid ranks. To exploit this situation even further, Sa'd ordered a general attack, and the two armies clashed once again. Despite the Muslims' repeated charges, the Sassanids held their ground. In the absence of the Persian elephants, the Muslims once again brought up camels camouflaged as monsters. The trick did not work this time, and the Persian horses stood their ground.

The third day of the battle was the hardest for both armies. There were heavy casualties on both sides, and the battlefield was strewn with the dead bodies of fallen warriors. Despite the fatigue after three days of battle, the armies continued the fight, which raged through the night and ended at dawn. It became a battle of stamina, with both sides on the verge of breaking. Sa'd's strategy was to wear down the Persians and snatch victory from them. In the Muslim chronicles, the third day of the battle is known as Yaum-ul-Amas and the night as Lailat-ul-Harir, meaning the "Night of Rumbling Noises".

Day 4

At sunrise of 19 November 636, the fighting had ceased, but the battle was still inconclusive. Qa'qa, with the consent of Sa'd, was now acting as the field commander of the Muslim troops. He is reported to have addressed his men as follows:

"If we fight for an hour or so more, the enemy will be defeated. So, warriors of Bani Tameem make one more attempt and victory will be yours."

The Muslims' left centre led by Qa’qa surged forward and attacked the Sassanid right centre, followed by the general attack of the Muslim corps. The Sassanids were taken by surprise at the resumption of battle. The Sassanid left wing and left centre were pushed back. Qa’qa again led a group of Mubarizuns against the Sassanids' left centre and by noon, he and his men were able to pierce through the Sassanid centre. However, they were unable to break the Persian army.

Final battle

On the final day, Rostam was slain, which heralded the defeat of the Persians. Multiple different accounts have been told of his mysterious death:

1) Qa'qa and his men dashed toward the Sassanid headquarters. Meanwhile, in the middle of a sandstorm, Rostam was found dead with over 5 wounds on his body. The Persians were not aware of his death, though, and continued to fight. The Sassanid right wing counter-attacked and regained its lost position, and the Muslims' left wing retreated to its original position. The Muslims' left centre, now under Qa’qa's command, when denied the support of their left wing, also retreated to its original position. Sa'd now ordered a general attack on the Sassanid front to drive away the Persians, who were demoralized by the death of their charismatic leader. In the afternoon, the Muslims mounted another attack.

2) There was a heavy sandstorm facing the Persian army on the final day of the battle. Rostam lay next to a camel to shelter himself from the storm, while some weapons, such as axes, maces, and swords had been loaded on the camel. Hilāl ibn 'Ullafah accidentally cut the girdle of the load on the camel, not knowing that Rostam was behind and under it. The weapons fell on Rostam and broke his back leaving him half-dead and paralyzed. Hilal beheaded Rostam and shouted, "I swear by the god of Kaaba that I have killed Rostam." Shocked by the head of their legendary leader dangling before their eyes, the Persians were demoralized, and the commanders lost control of the army. Many Persian soldiers were slain in the chaos, many escaped through the river, and finally, the rest of the army surrendered. This account has been dismissed as unlikely due to several problems with the story, including the presence of suspicious literary devices and general inconsistencies in the narrative.[12]

3) A version from Ya'qubi records that Dhiraar bin Al-Azwar, Tulayha, Amru bin Ma'adi Yakrib, and Kurt bin Jammah al-Abdi discovered the corpse of Rostam.[13]

4) Yet another version states that Rostam was killed during single combat with Sa'd during which the former was slain while temporarily blinded by the sandstorm. However, like the Al-Tabari, is likely an invention of later story-tellers.[12]

The Sassanid front, after putting up a last stand, finally collapsed; part of the Sassanid army retreated in an organized manner while the rest retreated in panic towards the river. At this stage Jalinus took command of what was left of the Sassanid army and claimed control of the bridgehead, succeeding in getting the bulk of the army across the bridge safely. The battle of al-Qadisiyyah was over, and the Muslims were victorious. Sa'd sent the cavalry regiments in various directions to pursue the fleeing Persians. The stragglers that the Muslims met along the way were either killed or taken captive. Heavy casualties were suffered by the Sassanids during these pursuits.

Aftermath

From this battle, the Arab Muslims gained a large number of spoils, including the famed jewel-encrusted royal standard, called the Derafsh-e-Kāveyān (the 'flag of Kāveh'). The jewel was cut up and sold in pieces in Medina.[14] The Arab fighters became known as 'Ahl al-Qādisiyyah',[citation needed] or "Ahl al-Qawadis",[15] and held the highest prestige among later Arab settlers within Iraq and its important garrison town, Kufa.

Once the battle of Qadisiyya was over, Sa'd sent a report of the Muslim victory to Umar. The battle shook Sassanian rule in Iraq to its foundations but was not the end of their rule in Iraq. As long as the Sassanids held their capital Ctesiphon, there was always the danger that at some suitable moment they would attempt to recover what they had lost and drive away the Arabs from Iraq. Caliph Umar thus sent instructions to Saad that as a sequel to the battle of Qadisiyyah, the Muslims should push forward to capture Ctesiphon. The Siege of Ctesiphon continued for two months, and the city was finally taken in March 637. Muslim forces conquered the Persian provinces up to Khuzistan. The conquest was slowed, however, by a severe drought in Arabia in 638 and the plague in southern Iraq and Syria in 639. After this, Caliph Umar wanted a break to manage the conquered territories and for then he wanted to leave the rest of Persia to the Persians. Umar is reported to have said:

"I wish there were a mountain of fire between us and the Persians, so that neither they could get to us, nor we to them."

The Persian perspective, however, was the polar opposite: one of great embarrassment, humiliation, and scorn. The pride of the imperial Sassanids had been hurt by the conquest of Iraq by the Arabs, and the Sassanids continued the struggle to regain the lost territory. Thus, a major Persian counterattack was launched and repulsed at the Battle of Nahavand, fought in December 641.

After that, a full-scale invasion of the Sassanid Empire was planned by Umar to conquer his arch-rival entirely. The last Persian emperor was Yazdgerd III, who was killed in 651 during the reign of the Caliph Uthman. His death officially marked the end of the Sassanid royal lineage and empire.

See also

Notes

- ^ According to Daryaee, "Islamic texts usually report the number of the Persian soldiers to have been in the hundreds or tens of thousands and several times larger than the Arab armies. This is pure fiction and it is boastful literature which aims to aggrandize Arab Muslim achievement, which may be compared to the Greek accounts of the Greco-Persian wars."[6]

- ^ Alternatively spelled Qadisiyah, Qadisiyya, Ghadesiyeh, or Kadisiya.

- ^ This was not a tactic of deception but an implementation of the command of Muhammad, who used to order his troops to call the enemy to Islam before engaging them in battle.[11]

References

- ^ a b Crawford 2013, p. 138.

- ^ Pourshariati 2011, p. 157.

- ^ Pourshariati 2011, p. 232-233, 269.

- ^ a b Pourshariati 2011, p. 232-233.

- ^ Dupuy & Dupuy 1996, p. 249.

- ^ Daryaee 2014, p. 37.

- ^ a b Morony 1986.

- ^ Lewental 2014.

- ^ Shahbazi 2005.

- ^ a b c Akram 1970, p. ??.

- ^ Akram 1970, p. 133.

- ^ a b Lewental 2016.

- ^ Hitti 2005, p. 415.

- ^ Inlow 1979, p. 13.

- ^ Djaït 1976, p. 151-152.

Sources

- Akram, A. I. (1970). The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. Nat. Publishing House. Rawalpindi. ISBN 0-7101-0104-X.

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.

- Djaït, Hichem (1976). "Les Yamanites à Kūfa au ier siècle de l'Hégire". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (in French). 19 (2): 151–152. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- Dupuy, Trevor N; Dupuy, R. Ernest (1996). "634-637. Operations in Persia". The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. HarperCollins.

- Hitti, Phillip Khuri (2005). The Origins of the Islamic State. p. 415.

- Inlow, E. Burke (1979). Shahanshah: A Study of Monarchy of Iran. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Lewental, D. Gershon (2014). "Qadesiya, Battle of". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Lewental, D. (2016). Rostam b. Farroḵ-Hormozd.

- Morony, M. (1986). "ARAB ii. Arab conquest of Iran". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Pourshariati, Parvenah (2011). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire. I.B. Tauris.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian Dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica.