Ted Radcliffe

| Ted Radcliffe | |

|---|---|

Ted Radcliffe c. 1935 | |

| Pitcher, Catcher | |

| Born: July 7, 1902 Mobile, Alabama, U.S. | |

| Died: August 11, 2005 (aged 103) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| Negro league baseball debut | |

| 1929, for the Chicago American Giants | |

| Last Negro league baseball appearance | |

| 1946, for the Homestead Grays | |

| Career statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 32–24 |

| Earned run average | 3.68 |

| Strikeouts | 216 |

| Batting average | .271 |

| Home runs | 17 |

| Run batted in | 183 |

| Managerial record | 165–148–5 |

| Teams | |

As player

As manager

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Theodore Roosevelt "Double Duty" Radcliffe (July 7, 1902 – August 11, 2005) was a professional baseball player in the Negro leagues. An accomplished two-way player, he played as a pitcher and a catcher, became a manager, and in his old age became a popular ambassador for the game. He is one of only a handful of professional baseball players who lived past their 100th birthdays, next to Red Hoff (who lived to 107) and fellow Negro leaguer Silas Simmons (who lived to age 111).

Newspaperman Damon Runyon coined the nickname "Double Duty" because Radcliffe played as a catcher and as a pitcher in the successive games of a 1932 doubleheader between the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the New York Black Yankees.[1] In the first of the two games at Yankee Stadium, Radcliffe caught the pitcher Satchel Paige for a shutout and then pitched a shutout in the second game. Runyon wrote that Radcliffe "was worth the price of two admissions." Radcliffe considered his year with the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords to be one of the highlights of his career.[2]

Of the six East–West All-Star Games in which he played, Radcliffe pitched in three and was a catcher in three. He also pitched in two and caught in six other All-Star games. He hit .376 (11-for-29) in nine exhibition games against major leaguers.[2]

Career

[edit]Early life

[edit]Ted Radcliffe grew up in Mobile, Alabama as one of ten children. His brother Alex Radcliffe also achieved renown as a ballplayer playing third base. The boys played baseball using a taped ball of rags with their friends including future Negro league All-Star ballplayers Leroy "Satchel" Paige and Bobby Robinson.

In 1919, teenagers Ted and Alex hitchhiked north to Chicago to join an older brother. The rest of the family soon followed to live on the South Side of Chicago. A year later Ted Radcliffe signed on with the semi-pro Illinois Giants at $50 for every 15 games and 50¢ a day for meal money. This worked out at about $100 a month. He travelled with the Giants for a few seasons before joining Gilkerson's Union Giants, another semi-pro team with whom he played until he entered the Negro National League with the Detroit Stars in 1928.

Pro ball

[edit]After a brief tenure with the Detroit Stars, Radcliffe played for the St. Louis Stars (1930), Homestead Grays (1931), Pittsburgh Crawfords (1932), Columbus Blue Birds (1933), New York Black Yankees, Brooklyn Eagles, Cincinnati Tigers, Memphis Red Sox, Birmingham Black Barons, Chicago American Giants, Louisville Buckeyes and Kansas City Monarchs.[2] Ted Radcliffe managed the Cincinnati Tigers in 1937, Memphis Red Sox in 1938 and Chicago American Giants in 1943.[2]

Radcliffe was known as a glib, fast-talking player. Ty Cobb reported that Radcliffe wore a chest protector that said "thou shalt not steal" during one exhibition game. He could call a clever game as a catcher and his banter from the pitching mound distracted some hitters. Biographer Kyle P. McNary estimates that Radcliffe had a .303 batting average, 4,000 hits and 400 homers in 36 years in the game (see Baseball statistics).[2]

Standing 5 ft 9 in and weighing 210 pounds (95 kg) Radcliffe had a strong throwing arm, good catching reflexes and great cunning. Even with these strengths, he also mastered many illegal pitches including the emery ball, the cut ball and the spitter. Statistics for the Negro league baseball are incomplete, but available records show him hitting .273 over eight of his 23 seasons.[2]

With the Detroit Stars, he was the regular catcher for the first half of the season. When the pitching staff grew tired, he began pitching and led the team to championship. His career high for batting average was .316 for the 1929 Detroit Stars.[2]

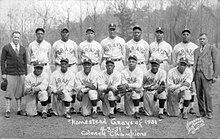

Radcliffe believed the Homestead Grays 1931 team to be the greatest team of all time. The side included Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, Jud Wilson, and Smokey Joe Williams. Gibson and Charleston joined him in the 1932 Pittsburgh Crawfords. Radcliffe and his close friend Satchel Paige were easily persuaded to change sides by offers of higher earnings and both moved frequently. They also formed several Negro league all-star teams to play exhibition games against white major league stars. By the end of his career Radcliffe had played for 30 different teams; in one season alone, he played on five different teams.[2]

Radcliffe was player-manager of the integrated Jamestown Red Sox of North Dakota from May to October 1934.[3] This made him the first black man to manage white professional players. He also played for the Chicago American Giants in that season. During that postseason, he managed a white semi-pro North Dakota team that toured Canada playing a major league all-star team gathered by Jimmie Foxx. Radcliffe's team won two games out of three before Foxx was hit on the head by a Chet Brewer pitch and the tour cancelled.[2]

In the next season, Radcliffe had trouble securing his release from the Brooklyn Eagles of the Negro leagues, but on June 21 he joined the integrated Bismarck Churchills. Along with Satchel Paige, Moose Johnson, and others, Radcliffe helped to lead the club to the first National Semipro Championship. This North Dakota team was owned by Neil Churchill, a car dealer. Other Negro leaguers on the team included Chet Brewer, Hilton Smith, Barney Morris and Quincy Trouppe.[2]

Radcliffe managed the Memphis Red Sox in 1937 as well as catching and pitching for them. He stayed there for 1938 and in 1943, aged 41, he rejoined the Chicago American Giants. Despite his age, Radcliffe won the Negro American League MVP award that season and a year later he struck a home run into the upper deck of Comiskey Park for the highlight of that season's East-West All-Star game.[2]

In 1945 Radcliffe played for the Kansas City Monarchs and roomed with Jackie Robinson. He integrated two semipro leagues, the Southern Minny (Minnesota) and the Michigan-Indiana League in 1948, by signing black and white players. In 1950 Radcliffe managed the Chicago American Giants of the Negro American League. The team's owner, Dr. J. B. Martin, was concerned about black players joining Major League teams; he instructed Radcliffe to sign white players. Radcliffe recruited at least five young white players, including Lou Chirban and Lou Clarizio.[2]

As player-manager with the Elmwood Giants in the Manitoba-Dakota League in 1951, Radcliffe batted .459 with a 3–0 pitching record; in 1952, at the age of 50, he batted .364 with a 1–0 pitching mark. A 1952 Pittsburgh Courier poll of Negro league experts named Double Duty the fifth greatest catcher in Negro league history and the 17th greatest pitcher. He retired two years later as a player-manager in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. His peak earnings had been $850 a month; the top rate for a major league player of the time was $10,000, paid monthly to Hank Greenberg in 1947.[2]

In the 1960s, Radcliffe was employed as a baseball scout including for a time with the Cleveland Indians.[4]

Segregation

[edit]Throughout his career, Double Duty had to endure racial segregation. In every city except Saint Paul, Minnesota, he and his colleagues had to stay in segregated hotels and eat in segregated restaurants. It was difficult to get cabs at night. He also faced racist hostility from players and has said that, among others, "Ty Cobb didn't like colored people". Radcliffe also recalled stopping the team car to buy gas in Waycross, Georgia. When the players tried to drink water from the car wash hose, the owner of the gas station told them, "Put that hose down—that's for white folks to drink." Radcliffe told a Boston Globe interviewer: "After that, I refused to buy gas from him. About four miles down the road, the gas ran out and we had to push the car five miles."[2]

Retirement

[edit]After leaving baseball, Radcliffe and his wife returned to a life of poverty until 1990, when they were robbed and beaten in their housing project on Chicago's South Side. A news report of this came to the attention of the Baseball Assistance Team, a charity that helps needy ex-players. With the help of the mayor's office, the team helped the couple move into a church-run residence for the elderly.[4]

Writer Kyle McNary met Radcliffe in 1992 when he was trying to learn more about black baseball in his home town of Bismarck, North Dakota. Radcliffe subsequently suggested that McNary should write his biography and the result was self-published by McNary in 1994. Radcliffe would travel widely to ballgames and became known for his lively good humor and gentle clowning.[2]

Despite two strokes and other age-related health problems, Radcliffe continued to be active in his community. He received the state of Illinois Historical Committee's Lifetime Achievement Award and was honored by Mayor Richard Daley as an outstanding citizen of Chicago. He has been the guest of three U.S. Presidents at the White House. A WGN documentary about Radcliffe's life, narrated by Morgan Freeman, won an Emmy Award. The Illinois Department of Aging inducted him into their Hall of Fame in 2002.[5]

In 1997, Radcliffe was inducted into the "Yesterday's Negro League Baseball Players Wall of Fame" at County Stadium in Milwaukee. In 1999, aged 96, he became the oldest player to appear in a professional game just ahead of Buck O'Neil and Jim Eriotes. He threw a single pitch for the Schaumburg Flyers of the Northern League. After his 100th birthday, Double Duty celebrated each year by throwing a ceremonial first pitch for the Chicago White Sox at U.S. Cellular Field. On July 27, 2005, he threw the first pitch at Rickwood Field, Birmingham, Alabama.[6] Two weeks later, Radcliffe died in Chicago on August 11, 2005, due to complications from cancer.

Radcliffe's stories were entertaining but not always reliable. His claim to have seen Fidel Castro with a cigar at a winter game in Cuba and his observation that the man "couldn't play" seems unlikely given that Castro would have been just 14 at the time.

Raelee Frazier cast Ted Radcliffe's twisted broken hands in bronze as part of the 2003 Hitters Hands series of baseball sculptures that toured the United States in Shades of Greatness, an exhibition sponsored by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.[7]

Bibliography

[edit]- 'Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe', Jet, July 22, 1996 ISSN 0021-5996

- 'Still Loving Baseball At 100', Jet, (June 9, 2003) ISSN 0021-5996

- 'Honoring Legends', Jet, July 28, 2003 ISSN 0021-5996

- 'Celebrating 102!', Jet, July 26, 2004 ISSN 0021-5996

- '2002 Hall of Fame Inductees', Illinois Department of Aging (2002). Retrieved July 24, 2005.

- '"Double Duty" Knows Baseball' Los Angeles Times, June 20, 2003.

- 'Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe', Negro League Baseball Players Association (2005)

- 'Exciting to watch, Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe', The African America Registry (2005)

- 'Ted Radcliffe Biography', The History Makers (2005)

- 'Double-Duty to throw out first pitch', Birmingham News, July 22, 2005. Retrieved July 24, 2005.

- Blake, Mike. Baseball Chronicles, (Cincinnati, Oh: Betterway Books, 1994)

- Bogira, Steve. 'Blackball: Memories of the Negro Leagues and Notes On the Integration, To Use the Term Loosely, of Major League Baseball', City Paper (Washington (DC)), July 24, 1987 (Vol. 7, Issue 30) pp. 12–24

- Floto, James. 'Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe: 36 Years of Pitching & Catching in Baseball's Negro Leagues', The Diamond Angle (October 2001)

- Gadfly. 'Hall of Merit discussion: Ted Radcliffe', Baseball Think Factory (May 2005) Retrieved July 25, 2005

- Goldstein, Richard. 'Ted Radcliffe, Star of the Negro Leagues, Is Dead at 103', The New York Times (August 12, 2005)

- Hershberger, Chuck. 'Baseball Book Review', Oldtyme Baseball News 1995 (Vol. 6, Issue 5) p. 28

- Holway, John B. Voices From The Great Black Baseball Leagues (New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1975) (Revised Edition published New York: Da Capo Press, 1992)

- Larry Lester, Sammy J. Miller and Dick Clark, Black Baseball in Chicago, (Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2000) ISBN 0-7385-0704-0

- Ted Radcliffe - Baseballbiography.com

- McNary, Kyle P. Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe: 36 Years Of Pitching & Catching In Baseball's Negro Leagues (Minneapolis: McNary Publishing, 1994)

- McNary, Kyle P. 'North Dakota Whips Big Leagues', Pitch Black Baseball (2001) Archived 2008-07-25 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 25, 2005.

- McNary, Kyle P. 'Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe', Simply Baseball Notebook: Legends (March 2002)

- McNary, Kyle P. 'Negro Leaguer of the Month, July, 2004', Pitch Black Baseball (July 2004)

- Peterson, Robert W. Only The Ball Was White, (New York: Prentice-Hall Englewood-Cliffs, 1970)

- Sepulveda, Lefty. 'Grateful Memories of Ted "Double Duty" Radcliffe', Baseball Library (August 2, 2002)

- Smith, Shelley. 'Remembering Their Game', Sports Illustrated, July 6, 1992 (Vol. 77, Issue 1) p. 80

- Smith, Wendell. 'East-West Star Dust', Pittsburgh Courier, August 19, 1944

- Steele, David. 'Negro Leaguers Seek Entry Into Hall', USA Today Baseball Weekly, August 16, 1991 (Vol. 1, Issue 20) p. 17

References

[edit]- ^ "Ted Radcliffe". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o McNary 1994

- ^ Gadfly

- ^ a b Goldstein

- ^ "2002 Hall of Fame: Performance and Graphic Arts - Theodore 'Double Duty' Radcliffe," Illinois Department of Aging website. Retrieved Aug. 22, 2020.

- ^ Birmingham News, 22 July 2005

- ^ Frazier

External links

[edit]- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or Baseball Reference and Baseball-Reference Black Baseball and stats and Seamheads

- Ted Radcliffe at Find a Grave

- Ted Radcliffe at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- 1902 births

- 2005 deaths

- African-American baseball players

- African-American centenarians

- American men centenarians

- American expatriate baseball players in Mexico

- Azules de Veracruz players

- Birmingham Black Barons players

- Bismarck Churchills players

- Brooklyn Eagles players

- Chicago American Giants players

- Cincinnati Tigers (baseball) players

- Columbus Blue Birds players

- Deaths from cancer in Illinois

- Detroit Stars players

- Elmwood Giants players

- Homestead Grays players

- Kansas City Monarchs players

- Louisville Buckeyes players

- Memphis Red Sox players

- Mexican League baseball players

- Negro league baseball managers

- New York Black Yankees players

- Pittsburgh Crawfords players

- St. Louis Stars (baseball) players

- Baseball players from Mobile, Alabama

- 20th-century African-American sportspeople

- 21st-century African-American sportspeople