Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Denarius depicting Mark Antony minted by Marcus Barbatius. Legend: m(arcus) ant(onius) imp aug iiivir rpc m(arcus) barbatius q p[note 1] | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | 14 January 83 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | 1 August 30 BC (aged 53) | ||||||||||||||||

| Cause of death | Suicide | ||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Unlocated tomb (probably in Egypt) | ||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Roman | ||||||||||||||||

| Office |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Spouses |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Marcus Antonius Creticus and Julia | ||||||||||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Roman Republic Julius Caesar | ||||||||||||||||

| Years | 54–30 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| Battles / wars | |||||||||||||||||

Marcus Antonius (14 January 83 BC – 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony,[1] was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

Antony was a relative and supporter of Julius Caesar, and he served as one of his generals during the conquest of Gaul and Caesar's civil war. Antony was appointed administrator of Italy while Caesar eliminated political opponents in Greece, North Africa, and Spain. After Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, Antony joined forces with Lepidus, another of Caesar's generals, and Octavian, Caesar's great-nephew and adopted son, forming a three-man dictatorship known to historians as the Second Triumvirate. The Triumvirs defeated Caesar's killers, the Liberatores, at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, and divided the government of the Republic among themselves. Antony was assigned Rome's eastern provinces, including the client kingdom of Egypt, then ruled by Cleopatra VII Philopator, and was given the command in Rome's war against Parthia.

Relations among the triumvirs were strained as the various members sought greater political power. Civil war between Antony and Octavian was averted in 40 BC, when Antony married Octavian's sister, Octavia. Despite this marriage, Antony carried on a love affair with Cleopatra, who bore him three children, further straining Antony's relations with Octavian. Lepidus was expelled from the association in 36 BC, and in 33 BC, disagreements between Antony and Octavian caused a split between the remaining Triumvirs. Their ongoing hostility erupted into civil war in 31 BC when Octavian induced the republic to declare war on Cleopatra and proclaim Antony a traitor. Later that year, Antony was defeated by Octavian's forces at the Battle of Actium. Antony and Cleopatra fled to Egypt where, having again been defeated at the Battle of Alexandria, they committed suicide.

With Antony dead, Octavian became the undisputed master of the Roman world. In 27 BC, Octavian was granted the title of Augustus, marking the final stage in the transformation of the Republic into a monarchy, with himself as the first Roman emperor.

Early life

[edit]A member of the plebeian gens Antonia, Antony was born in Rome[2] on 14 January 83 BC.[3][4] His father and namesake was Marcus Antonius Creticus, son of the noted orator Marcus Antonius who had been murdered during the purges of Gaius Marius in the winter of 87–86 BC.[5] His mother was Julia, a third cousin of Julius Caesar. Antony was an infant at the time of Lucius Cornelius Sulla's march on Rome in 82 BC.[6][note 2]

According to the Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, Antony's father was incompetent and corrupt, and was only given power because he was incapable of using or abusing it effectively.[7] In 74 BC he was given the military command to defeat the pirates of the Mediterranean, but he died in Crete in 71 BC without making any significant progress.[5][7][8] The elder Antony's death left Antony and his brothers, Lucius and Gaius, in the care of their mother, Julia, who later married Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, an eminent member of the old patrician nobility. Lentulus, despite exploiting his political success for financial gain, was constantly in debt due to his extravagance. He was a major figure in the Catilinarian conspiracy and was summarily executed on the orders of the consul Cicero in 63 BC for his involvement.[9]

According to the historian Plutarch, Antony spent his teenage years wandering through Rome with his brothers and friends gambling, drinking, and becoming involved in scandalous love affairs.[8] Antony's contemporary and enemy, Cicero, charged that he had a homosexual relationship with Gaius Scribonius Curio.[10] This form of slander was popular during this time in the Roman Republic to demean and discredit political opponents.[11][12] There is little reliable information on his political activity as a young man, although it is known that he was an associate of Publius Clodius Pulcher and his street gang.[13] He may also have been involved in the Lupercal cult as he was referred to as a priest of this order later in life.[14] By age twenty, Antony had amassed an enormous debt. Hoping to escape his creditors, Antony fled to Greece in 58 BC, where he studied philosophy and rhetoric at Athens.[citation needed]

Early career and occupation

[edit]In 57 BC, Antony joined the military staff of Aulus Gabinius, the Proconsul of Syria, as commander of the cavalry.[15] This appointment marks the beginning of his military career.[16] As consul the previous year, Gabinius had consented to the exile of Cicero by Antony's mentor, Publius Clodius Pulcher.

Hyrcanus II, the Roman-supported Hasmonean High Priest of Judea, fled Jerusalem to Gabinius to seek protection against his rival and son-in-law Alexander. Years earlier in 63 BC, the Roman general Pompey had captured him and his father, King Aristobulus II, during his war against the declining Seleucid Empire. Pompey had deposed Aristobulus and installed Hyrcanus as Rome's client ruler over Judea.[17] Antony achieved his first military distinctions after securing important victories at Alexandrium and Machaerus.[18] With the rebellion defeated by 56 BC, Gabinius restored Hyrcanus to his position as High Priest in Judea.

The following year, in 55 BC, Gabinius intervened in the political affairs of Ptolemaic Egypt. Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes had been deposed in a rebellion led by his daughter Berenice IV in 58 BC, forcing him to seek asylum in Rome. During Pompey's conquests years earlier, Ptolemy had received the support of Pompey, who named him an ally of Rome.[21] Gabinius' invasion sought to restore Ptolemy to his throne. This was done against the orders of the senate but with the approval of Pompey, then Rome's leading politician, and only after the deposed king provided a 10,000 talent bribe. The Greek historian Plutarch records it was Antony who convinced Gabinius to finally act.[18] After defeating the frontier forces of the Egyptian kingdom, Gabinius' army proceeded to attack the palace guards but they surrendered before a battle commenced.[22] With Ptolemy XII restored as Rome's client king, Gabinius garrisoned two thousand Roman soldiers, later known as the Gabiniani, in Alexandria to ensure Ptolemy's authority. In return for its support, Rome exercised considerable power over the kingdom's affairs, particularly control of the kingdom's revenues and crop yields.[23] Antony claimed years later to have first met Cleopatra, the then 14-year-old daughter of Ptolemy XII, during this Egyptian campaign.[24]

While Antony was serving Gabinius in the East, the domestic political situation had changed in Rome. In 60 BC, a secret agreement (known as the "First Triumvirate") was entered into between three men to control the Republic: Marcus Licinius Crassus, Gnaeus Pompey Magnus, and Gaius Julius Caesar. Crassus, Rome's wealthiest man, had defeated the slave rebellion of Spartacus in 70 BC; Pompey conquered much of the Eastern Mediterranean in the 60's BC; Caesar was Rome's pontifex maximus and a former general in Spain. Caesar, with funding from Crassus, was elected consul for 59 BC to pursue legislation favourable to the allies' interests. Caesar, for his part, was made proconsular governor Illyricum, Cisalpine Gaul, and Transalpine Gaul for five years. Caesar used his governorship as a launching point for his conquest of free Gaul. Some years later, in the midst of a breakdown in the alliance, the allies again pursued their interests together: in 55 BC, Crassus and Pompey were elected consuls in disputed elections and Caesar's command was extended for another five years.[25][26]

During his early military service, Antony married his cousin Antonia Hybrida Minor, the daughter of Gaius Antonius Hybrida. Sometime between 54 and 47 BC, the union produced a single known child, Antonia. It is unclear if this was Antony's first marriage.[note 4]

Service under Caesar

[edit]Gallic wars

[edit]

Antony's association with Publius Clodius Pulcher allowed him to achieve greater prominence. Clodius, through the influence of his benefactor Marcus Licinius Crassus, had developed a positive political relationship with Julius Caesar. Clodius secured Antony a position on Caesar's military staff in 54 BC, joining his conquest of Gaul. Serving under Caesar, Antony demonstrated excellent military leadership. Despite a temporary alienation later in life, Antony and Caesar developed friendly relations which would continue until Caesar's assassination in 44 BC. Caesar's influence secured greater political advancement for Antony. After a year of service in Gaul, Caesar dispatched Antony to Rome to formally begin his political career, receiving election as quaestor for 52 BC. Assigned to assist Caesar, Antony returned to Gaul and commanded Caesar's cavalry during his victory at the Battle of Alesia against the Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix. Following his year in office, Antony was made one of Caesar's legates and assigned command of two legions (approximately 7,500 total soldiers).[27]

Meanwhile, the alliance among Caesar, Pompey and Crassus had effectively ended. Caesar's glory in conquering Gaul had served to further strain his alliance with Pompey,[28] who, having grown jealous of his former ally, had drifted away from Caesar and towards Cato and his allies. The domestic political situation in Rome was tense, with multiple politicians leading large street gangs. Two important ones, were led by Clodius and his rival Titus Annius Milo. In 52 BC with elections unable to be held by the gangs' open violence and obstruction from radical tribunes, Milo encountered Clodius on a road outside Rome (both with entourages), which ended with Clodius' death. The violent ad hoc funeral held for Clodius resulted in widespread rioting and the destruction of the senate house, the curia Hostilia. Elevating Pompey to restore order and hold elections, the senate induced his election as sole consul.[29] Fully secure in his political position, Pompey distanced himself from Caesar over the following years.

Antony remained on Caesar's military staff until 50 BC, helping mopping-up actions across Gaul to secure Caesar's conquest. With the war largely over, Antony was sent back to Rome to act as Caesar's protector. With the support of Caesar, Antony was appointed to the College of Augurs, an important priestly office responsible for interpreting the will of the gods by studying the flight of birds. All public actions required favorable auspices, granting the college considerable influence. Antony was then elected as one of the ten plebeian tribunes for 49 BC. In this position, Antony could protect Caesar from his political enemies, by vetoing actions unfavorable to his patron.

Civil war

[edit]

The feud between Caesar and Pompey erupted into open confrontation by early 49 BC. The consuls for the year, Gaius Claudius Marcellus and Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Crus, opposed Caesar.[30] Pompey, though remaining in Rome, was then serving as the governor of Spain and commanded several legions. Throughout 50 BC an uneasy set of negotiations had been ongoing between Caesar and the senate, with Caesar demanding the right to stand for the consulship while in command of his forces in absentia. Antony again brought up the proposal of the younger Curio that Caesar and Pompey lay down their commands and return to the status of private citizens.[31] His proposal was well received by most of the senators but the consuls and Cato vehemently opposed it. Antony then made a new proposal: Caesar would retain only two of his eight legions and the governorship of Illyrium if he was allowed to stand for the consulship in absentia. Though Pompey found the concession satisfactory, Cato and Lentulus refused to back down. Antony fled Rome, claiming to fear for his life, and returned to Caesar's camp in Cisalpine Gaul.

Within days of Antony's withdrawal, 7 January 49 BC, the senate reconvened. Under the leadership of Cato and with the tacit support of Pompey, the senate passed a senatus consultum ultimum, a decree stripping Caesar of his command and ordering him to return to Rome and stand trial. The senate further declared Caesar a public enemy if he did not immediately disband his army.[32] With all hopes of finding a peaceful solution gone, Caesar used Antony as a pretext for marching on Rome. As tribune, Antony's person was sacrosanct, so it was unlawful to harm him or to refuse to recognize his veto. Three days later, on 10 January, Caesar crossed the Rubicon, initiating the civil war.[33]

Caesar's rapid advance surprised Pompey, who withdrew from Italy to Greece. After entering Rome, instead of pursuing Pompey, Caesar marched to Spain to defeat the Pompeian loyalists there. Meanwhile, Antony, with the rank of propraetor, was installed as governor of Italy and commander of the army, stationed there while Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, one of Caesar's staff officers, ran the provisional administration of Rome itself.[34][35] Though Antony was well liked by his soldiers, most other citizens despised him for his lack of interest in the hardships they faced from the civil war.[36]

By the end of the year 49 BC, Caesar, already the ruler of Gaul, had captured Italy, Spain, Sicily, and Sardinia from his enemies. In early 48 BC, he prepared to sail with seven legions to Greece to face Pompey. Caesar had entrusted the defense of Illyricum to Gaius Antonius, Antony's younger brother, and Publius Cornelius Dolabella. Pompey's forces, however, defeated them and assumed control of the Adriatic Sea along with it. Additionally, the two legions they commanded defected to Pompey. Without their fleet, Caesar lacked the necessary transport ships to cross into Greece with his seven legions. Instead, he sailed with only two and placed Antony in command of the remaining five at Brundisium with instructions to join him as soon as he was able. In early 48 BC, Lucius Scribonius Libo was given command of Pompey's fleet, comprising some fifty galleys.[37][38] Moving off to Brundisium, he blockaded Antony. Antony, however, managed to trick Libo into pursuing some decoy ships, causing Libo's squadron to be trapped and attacked. Most of Libo's fleet managed to escape, but several of his ships were trapped and captured.[37][39] With Libo gone, Antony joined Caesar in Greece by March 48 BC.

During the Greek campaign, Plutarch records that Antony was Caesar's top general, and second only to him in reputation.[40] Antony joined Caesar at the western Balkan peninsula and besieged Pompey's larger army at Dyrrhachium. With food sources running low, Caesar, in July, ordered a nocturnal assault on Pompey's camp, but Pompey's larger forces pushed back the assault. Though an indecisive result, the victory was a tactical win for Pompey. Pompey, however, did not order a counterassault on Caesar's camp, allowing Caesar to retreat unhindered. Caesar would later remark the civil war would have ended that day if only Pompey had attacked him.[41] Caesar managed to retreat to Thessaly, with Pompey in pursuit.

Assuming a defensive position at the plain of Pharsalus, Caesar's army prepared for pitched battle with Pompey's, which outnumbered his own two to one. At the Battle of Pharsalus on 9 August 48 BC, Caesar commanded the right wing opposite Pompey while Antony commanded the left.[40] The resulting battle was a decisive victory for Caesar. Though the civil war did not end at Pharsalus, the battle marked the pinnacle of Caesar's power and effectively ended the Republic.[42] The battle gave Caesar a much needed boost in legitimacy, as prior to the battle much of the Roman world outside Italy supported Pompey and the senators around him as the legitimate Roman government. After Pompey's defeat, most of the senate defected to Caesar, including many of the soldiers who had fought under Pompey. Pompey himself fled to Ptolemaic Egypt, but Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator feared retribution from Caesar and had Pompey assassinated upon his arrival.

Governor of Italy

[edit]

After the battle, Caesar was made dictator in absentia, and appointed Antony as master of horse (his lieutenant).[43] Caesar without returning to Rome sailed for Egypt, where he took part in the Alexandrian war, deposing Ptolemy XIII in favour of Cleopatra, who became Caesar's mistress and bore him a son, Caesarion. Caesar's actions further strengthened Roman control over the already Roman-dominated kingdom.[44]

While Caesar was away in Egypt, Antony remained in Rome to govern Italy and restore order.[45] Without Caesar to guide him, however, Antony quickly faced political difficulties and proved himself unpopular. The chief cause of his political challenges concerned debt forgiveness. One of the tribunes for 47 BC, Publius Cornelius Dolabella, proposed a law which would have canceled all outstanding debts. Antony opposed the law for political and personal reasons: he believed Caesar would not support such massive relief and suspected Dolabella had seduced his wife Antonia Hybrida. When Dolabella sought to enact the law by force and seized the Forum, Antony responded by unleashing his soldiers upon the assembled masses, killing hundreds.[46] The resulting instability, especially among Caesar's veterans who would have benefited from the law, forced Caesar to return to Italy by October 47 BC.[45]

Antony's handling of the affair with Dolabella led to a cooling of his relationship with Caesar. Antony's violent reaction had caused Rome to fall into a state of anarchy. Caesar sought to mend relations with Dolabella; he was elected to a third term as consul for 46 BC, but proposed the senate should transfer the consulship to Dolabella. When Antony protested, Caesar was forced to withdraw the motion. Later, Caesar sought to exercise his prerogatives as dictator and directly proclaim Dolabella as consul instead.[47] Antony again protested and, in his capacity as an augur, declared the omens were unfavorable and Caesar again backed down.[48] Seeing the expediency of removing Dolabella from Rome, Caesar ultimately pardoned him for his role in the riots and took him as one of his generals in his campaign.[40] Antony, however, was stripped of all official positions and received no appointments for the year 46 BC or 45 BC. Instead of Antony, Caesar appointed Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to be his consular colleague for 46 BC; Lepidus also replaced Antony as master of horse for Caesar's various dictatorships.[43] While Caesar campaigned in North Africa, Antony remained in Rome as a mere private citizen. After returning victorious from North Africa, Caesar was appointed dictator for ten years and brought Cleopatra and their son to Rome. Antony again remained in Rome while Caesar, in 45 BC, sailed to Spain to defeat the final opposition to his rule; successful, the civil war ended.

Following the scandal with Dolabella, Antony had divorced his second wife and quickly married Fulvia. Fulvia had previously been married to both Publius Clodius Pulcher and Gaius Scribonius Curio, having been a widow since Curio's death in the battle of the Bagradas in 49 BC. Though Antony and Fulvia were formally married in 47 BC, Cicero suggests the two had been in a relationship since at least 58 BC.[49][50] The union produced two children: Marcus Antonius Antyllus (born 47) and Iullus Antonius (born 45).

Assassination of Caesar

[edit]Ides of March

[edit]Whatever conflicts existed between himself and Caesar, Antony remained faithful to Caesar, ensuring their estrangement did not last long. Antony reunited with Caesar at Narbo in 45 BC with full reconciliation coming in 44 BC when Antony was elected consul alongside Caesar. Caesar planned a new invasion of Parthia and desired to leave Antony in Italy to govern Rome in his name. The reconciliation came soon after Antony is said to have rejected an offer from Gaius Trebonius, one of Caesar's generals, to join a conspiracy to assassinate Caesar.[51][52] If such an offer was made, Antony made no mention of the matter to Caesar.

Soon after they assumed office together, the Lupercalia was held on 15 February 44 BC. The festival was held in honor of Lupa, the she-wolf who suckled the infant orphans Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome.[53] The political atmosphere of Rome at the time of the festival was deeply divided. Caesar had by this point centralised almost all political powers into his own hands. He was granted further honors, including a form of semi-official cult, with Antony as his high priest.[54] Additionally, on 1 January 44 BC, Caesar had been named dictator perpetuo, removing any formal end to his autocratic powers. Caesar's political rivals feared this dictatorship with no end date would transform the Republic into a monarchy, abolishing the centuries of rule by the senate and people. During the festival's activities, Antony publicly offered Caesar a diadem, which Caesar threw off. When Antony placed the diadem in his lap, Caesar ordered the diadem to be placed in the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.[55]

When Antony offered Caesar the crown, there had been minor applause but mostly silence from the crowd. When Caesar refused it, however, the crowd was enthusiastic.[56] The event presented a powerful message: a diadem was a symbol of a king. By refusing it, Caesar demonstrated he had no intention of making himself king. Antony's motive for such actions is not clear and it is unknown if he acted with Caesar's prior approval or on his own.[55] While commonly described as an event that was "scripted", who was central to planning it is unclear. One argument is that Antony moved forward with the gesture on his own accord, possibly to embarrass or flatter Caesar. A later claim was that he was actually trying to convince Caesar not to go through with a kingship. By other accounts, it was Caesar's enemies who planned the incident as a way to frame him, with it being claimed two enemies of Caesar approached him to argue he should take the diadem. Another theory, one especially popular at the time, was that Caesar himself had orchestrated the event to test public support on him becoming king.[57]

A group of senators resolved to kill Caesar to prevent him from establishing a monarchy. Chief among them were Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Although Cassius was "the moving spirit" in the plot, winning over the chief assassins to the cause of tyrannicide, Brutus, with his family's history of deposing Rome's kings, became their leader.[58] Cicero, though not personally involved in the conspiracy, later claimed Antony's actions sealed Caesar's fate as such an obvious display of Caesar's preeminence motivated them to act.[59] Originally, the conspirators had planned to eliminate not only Caesar but also many of his supporters, including Antony, but Brutus rejected the proposal, limiting the conspiracy to Caesar alone.[60] With Caesar preparing to depart for Parthia in late March, the conspirators prepared to act when Caesar appeared for the senate meeting on the Ides of March (15 March).

Antony also went with Caesar, but was waylaid at the door of the Theatre of Pompey by Trebonius and was distracted from aiding Caesar. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, as Caesar arrived at the senate, Lucius Tillius Cimber presented him with a petition to recall his exiled brother.[61] The other conspirators crowded round to offer their support. Within moments, the group of five conspirators stabbed Caesar one by one. Caesar attempted to get away, but, being drenched by blood, he tripped and fell. According to Roman historian Eutropius, around 60 or more men participated in the assassination. Caesar was stabbed 23 times and died from the blood loss attributable to multiple stab wounds.[62][63]

Leader of the Caesarians

[edit]In the turmoil surrounding the assassination, Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave, fearing Caesar's death would be the start of a bloodbath among his supporters. When this did not occur, he soon returned to Rome. The conspirators, who styled themselves the liberatores ("liberators"), had barricaded themselves on the Capitoline hill. Although they believed Caesar's death would restore the Republic, Caesar had been immensely popular with the Roman middle and lower classes, who became enraged upon learning a small group of aristocrats had killed their champion.

Antony, as the sole consul, soon took the initiative and seized the state treasury. Calpurnia, Caesar's widow, presented him with Caesar's personal papers and custody of his extensive property, clearly marking him as Caesar's heir and leader of the Caesarians.[64] Caesar's master of horse Marcus Aemilius Lepidus marched over 6,000 troops into Rome on 16 March to restore order and intimidate the liberatores. Lepidus wanted to storm the Capitol, but Antony preferred a peaceful solution as a majority of both the liberatores and Caesar's own supporters preferred a settlement over renewed civil war.[65] On 17 March, at Antony's arrangement, the senate met to discuss a compromise, which, due to the presence of Caesar's veterans in the city, was quickly reached. Caesar's assassins would be pardoned of their crimes and, in return, all of Caesar's actions would be ratified.[66] In particular, the offices assigned to both Brutus and Cassius by Caesar were likewise ratified. Antony also agreed to accept the appointment of his rival Dolabella as his consular colleague to replace Caesar.[67] This compromise was a great success for Antony, who managed to simultaneously appease Caesar's veterans, reconcile the senate majority, and appear to the liberatores as their partner.[68]

On 19 March, Caesar's will was opened and read. In it, Caesar posthumously adopted his great-nephew Gaius Octavius and named him his principal heir. Then only nineteen years old and stationed with Caesar's army in Macedonia, the youth became a member of Caesar's gens Julia with the name "Gaius Julius Caesar"; for clarity, it is historical convention to call him Octavian. Though not the chief beneficiary, Antony did receive some bequests.[69]

Shortly after the compromise was reached, as a sign of good faith, Brutus, against the advice of Cassius and Cicero, agreed Caesar would be given a public funeral and his will would be validated. Caesar's funeral was held on 20 March. Antony, as Caesar's faithful lieutenant and incumbent consul, was chosen to preside over the ceremony and to recite a eulogy. In a demagogic speech, he enumerated the deeds of Caesar and, publicly reading his will, detailed the donations Caesar had left to the Roman people. Antony then seized the blood-stained toga from Caesar's body and presented it to the crowd. Worked into a fury by the bloody spectacle, the assembly turned into a riot. Several buildings in the Forum and some houses of the conspirators were burned to the ground. Panicked, many of the conspirators fled Italy.[70] Under the pretext of not being able to guarantee their safety, Antony relieved Brutus and Cassius of their judicial duties in Rome and instead assigned them responsibility for procuring wheat for Rome from Sicily and Asia. Such an assignment, in addition to being unworthy of their rank, would have kept them far from Rome and shifted the balance towards Antony. Refusing such secondary duties, the two traveled to Greece instead. Additionally, Cleopatra left Rome to return to Egypt.

Despite the provisions of Caesar's will, Antony proceeded to act as leader of the Caesarians, including appropriating for himself a portion of Caesar's fortune rightfully belonging to Octavian. Antony enacted the lex Antonia, which formally abolished the dictatorship, in an attempt to consolidate his support among those who opposed Caesar's dictatorial rule. He also enacted a number of laws he purported to have found in Caesar's papers to ensure his popularity with Caesar's veterans, particularly by providing land grants to them. Lepidus, with Antony's support, was elected pontifex maximus, succeeding Caesar. To solidify the alliance between Antony and Lepidus, Antony's daughter Antonia Prima was engaged to Lepidus' homonymous son. Surrounding himself with a bodyguard of over six thousand of Caesar's veterans, Antony presented himself as Caesar's true successor, largely ignoring Octavian.[71]

First conflict with Octavian

[edit]Octavian arrived in Rome in May to claim his inheritance. Although Antony had amassed political support, Octavian still had opportunity to rival him as the leading member of the Caesarian faction. The senate increasingly viewed Antony as a new tyrant; Antony had also lost the support of many supporters of Caesar when he opposed the motion to elevate Caesar to divine status.[72] When Antony refused to relinquish Caesar's vast fortune to him, Octavian borrowed heavily to fulfill the bequests in Caesar's will to the Roman people and to his veterans, as well as to establish his own bodyguard of veterans.[73] This earned him the support of Caesarian sympathizers who hoped to use him as a means of eliminating Antony.[74] The senate, and Cicero in particular, viewed Antony as the greater danger of the two. By summer 44 BC, Antony was in a difficult political position: he could either denounce the liberatores as murderers and alienate the senate or he could maintain his support for the compromise and risk betraying Caesar's legacy, strengthening Octavian's position. In either case, his situation as ruler of Rome would be weakened. Roman historian Cassius Dio later recorded that while Antony, as consul, maintained the advantage in the relationship, the general affection of the Roman people was shifting to Octavian due to his status as Caesar's son.[75][76]

Supporting the senatorial faction against Antony, Octavian, in September 44 BC, encouraged the eminent senator Marcus Tullius Cicero to attack Antony in a series of speeches portraying him as a threat to the republic.[77][78] Risk of civil war between Antony and Octavian grew. Octavian continued to recruit Caesar's veterans to his side, away from Antony, with two of Antony's legions defecting in November 44 BC. At that time, Octavian, only a private citizen, lacked legal authority to command the Republic's armies, making his command illegal. With popular opinion in Rome turning against him and his consular term nearing its end, Antony attempted to secure a favorable military assignment to secure an army to protect himself. The senate, as was custom, assigned Antony and Dolabella the provinces of Macedonia and Syria, respectively, to govern in 43 BC after their consular terms expired. Antony, however, objected to the assignment, preferring to govern Cisalpine Gaul which was already controlled by Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar's assassins.[79][80] When Decimus refused to surrender his province, Antony marched north in December 44 BC with his remaining soldiers to take the province by force, besieging Decimus at Mutina.[81] The senate, led by a fiery Cicero, denounced Antony's actions and declared him an enemy of the state.

Ratifying Octavian's extraordinary command on 1 January 43 BC, the senate dispatched him along with consuls Hirtius and Pansa to defeat Antony and his exhausted five legions.[82][83] Antony's forces were defeated at the Battle of Mutina in April 43 BC, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. Both consuls were killed, however, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies, some eight legions.[84][85]

The Second Triumvirate

[edit]Forming the alliance

[edit]

With Antony defeated, the senate assigned command of the legions in northern Italy to Decimus. Sextus Pompey, son of Caesar's old rival Pompey Magnus, was given command of the Republic's fleet from his base in Sicily while Brutus and Cassius were granted the governorships of Macedonia and Syria respectively. These appointments attempted to renew the "republican" cause.[86] However, the eight legions serving under Octavian, composed largely of Caesar's veterans, refused to follow one of Caesar's murderers, allowing Octavian to retain his command. Meanwhile, Antony recovered his position by joining forces with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been assigned the governorship of Transalpine Gaul and Nearer Spain.[87] Antony sent Lepidus to Rome to broker a conciliation. Though he was an ardent Caesarian, Lepidus had maintained friendly relations with the senate and with Sextus Pompey. His legions, however, quickly joined Antony, giving him control over seventeen legions, the largest army in the West.[88]

By mid-May, Octavian began secret negotiations to form an alliance with Antony to unify the Caesarians against the liberatores. Remaining in Cisalpine Gaul, Octavian dispatched emissaries to Rome in July 43 BC demanding he be appointed consul to succeed Hirtius and Pansa and that the senate rescind the decree declaring Antony a public enemy.[89] When the senate refused, Octavian marched on Rome with his eight legions and assumed control of the city in August 43 BC. Octavian had himself irregularly elected consul with a cousin, rewarded his soldiers, and then set about prosecuting Caesar's murderers. Under the lex Pedia, all of the conspirators and Sextus Pompey were convicted "in absentia" and declared public enemies. Then, at the instigation of Lepidus, Octavian went to Cisalpine Gaul to meet Antony.

In November 43 BC, Octavian, Lepidus, and Antony met near Bononia.[90] After two days of discussions, the group agreed to establish a three man dictatorship to govern the Republic for five years, known to modern historians as the Second Triumvirate. They shared military command of the republic's armies and provinces among themselves: Antony received Gaul, Lepidus Spain, and Octavian (as the junior partner) Africa. They jointly governed Italy. The triumvirate would have to conquer the rest of Rome's holdings; Brutus and Cassius held the Eastern Mediterranean, and Sextus Pompey held the Mediterranean islands.[91] On 27 November 43 BC, the triumvirate was formally established by a new law, the lex Titia. Octavian and Antony reinforced their alliance through Octavian's marriage to Antony's stepdaughter, Claudia.

The primary objective of the triumvirate was to avenge Caesar's death and to make war upon his murderers. Before marching against Brutus and Cassius in the East, the triumvirs issued proscriptions against their enemies in Rome. The dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla had taken similar action to purge Rome of his opponents in 82 BC. The proscribed were named on public lists, stripped of citizenship, and outlawed. Their wealth and property were confiscated by the state, and rewards were offered to anyone who secured their arrest or death. With such encouragements, the proscription produced deadly results; two thousand equites were executed, and one third of the senate. Antony forced Octavian to give up Cicero, a personal enemy of Antony and friend of Octavian, who was then killed on 7 December. The confiscations helped replenish the state treasury, which had been depleted by Caesar's civil war the decade before; when this seemed insufficient to fund the imminent war against Brutus and Cassius, the triumvirs imposed new taxes, especially on the wealthy. By January 42 BC the proscription had ended; it had lasted two months, and though less bloody than Sulla's, it traumatized Roman society. A number of those named and outlawed had fled to either Sextus Pompey in Sicily or to the liberatores in the East.[92] Senators who swore loyalty to the triumvirate were allowed to keep their positions; on 1 January 42 BC, the senate officially deified Caesar as "The Divine Julius", and confirmed Antony's position as his high priest.

War against the Liberators

[edit]Due to the infighting within the triumvirate during 43 BC, Brutus and Cassius had assumed control of much of Rome's eastern territories, and amassed a large army. Before the triumvirate could cross the Adriatic into Greece, the triumvirate had to address the threat posed by Sextus Pompey and his fleet. From his base in Sicily, Sextus raided the Italian coast and blockaded the triumvirs. Octavian's friend and admiral Quintus Salvidienus Rufus thwarted an attack by Sextus against the southern Italian mainland at Rhegium, but Salvidienus was then defeated in the resulting naval battle because of the inexperience of his crews. Only when Antony arrived with his fleet was the blockade broken. Though the blockade was defeated, control of Sicily remained in Sextus' hand, but the defeat of the liberatores was the triumvirate's first priority.

In the summer of 42 BC, Octavian and Antony sailed for Macedonia to face the liberatores with nineteen legions, the vast majority of their army[93] (approximately 100,000 regular infantry plus supporting cavalry and irregular auxiliary units), leaving Rome under the administration of Lepidus. Likewise, the army of the liberatores also commanded an army of nineteen legions; their legions, however, were not at full strength while the legions of Antony and Octavian were.[93] While the triumvirs commanded a larger number of infantry, the Liberators commanded a larger cavalry contingent.[94] The liberatores, who controlled Macedonia, did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the Triumvirs' communications with their supply base in Italy. They had spent the previous months plundering Greek cities to swell their war-chest and had gathered in Thrace with the Roman legions from the Eastern provinces and levies from Rome's client kingdoms.

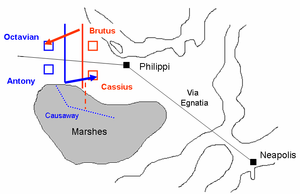

Brutus and Cassius held a position on the high ground along both sides of the via Egnatia west of the city of Philippi. The south position was anchored to a supposedly impassable marsh, while the north was bordered by impervious hills. They had plenty of time to fortify their position with a rampart and a ditch. Brutus put his camp on the north while Cassius occupied the south of the via Egnatia. Antony arrived shortly and positioned his army on the south of the via Egnatia, while Octavian put his legions north of the road. Antony offered battle several times, but the liberatores were not lured to leave their defensive stand. Thus, Antony tried to secretly outflank the Brutus and Cassius' position through the marshes in the south. This provoked a pitched battle on 3 October 42 BC. Antony commanded the triumvirate's army due to Octavian's sickness on the day, with Antony directly controlling the right flank opposite Cassius. Because of his health, Octavian remained in camp while his lieutenants assumed a position on the left flank opposite Brutus. In the resulting first battle of Philippi, Antony defeated Cassius and captured his camp while Brutus overran Octavian's troops and penetrated into the Triumvirs' camp but was unable to capture the sick Octavian. The battle was a tactical draw, but due to poor communications Cassius believed the battle was a complete defeat and committed suicide to prevent being captured.

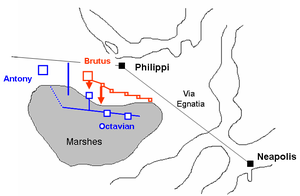

Brutus assumed sole command of the army and preferred a war of attrition over open conflict. His officers, however, were dissatisfied with these defensive tactics and his Caesarian veterans threatened to defect, forcing Brutus to give battle at the second battle of Philippi on 23 October. While the battle was initially evenly matched, Antony's leadership routed Brutus' forces. Brutus committed suicide the day after the defeat and the remainder of his army swore allegiance to the Triumvirate. Over fifty thousand Romans died in the two battles. While Antony treated the losers mildly, Octavian dealt cruelly with his prisoners and even beheaded Brutus' corpse.[95][96][97]

The battles of Philippi ended the civil war in favor of the triumvirs. With the defeat of Brutus and Cassius, only Sextus Pompey and his fleet remained to challenge the triumvirate's control of the Roman world.

Master of the Roman East

[edit]Division of the republic

[edit]

The victory at Philippi left the members of the triumvirate as masters of the republic, save Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Upon returning to Rome, the triumvirate repartitioned rule of Rome's provinces among themselves, with Antony as the clear senior partner. He received the largest distribution, governing all of the Eastern provinces while retaining Gaul in the West. Octavian's position improved, as he received Spain, which was taken from Lepidus. Lepidus was then reduced to holding only Africa, and he assumed a clearly tertiary role in the triumvirate. Rule over Italy remained undivided, but Octavian was assigned the difficult and unpopular task of demobilizing their veterans and providing them with land distributions in Italy.[98][99] Antony assumed direct control of the East while he installed one of his lieutenants as the ruler of Gaul. During his absence, several of his supporters held key positions in Rome to protect his interests there.

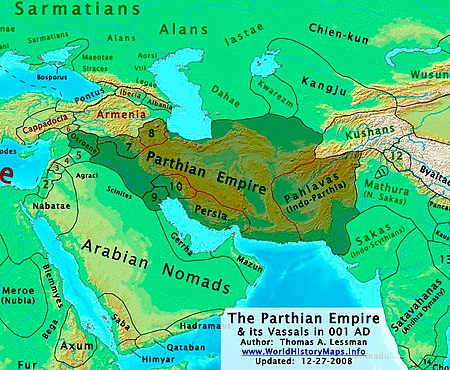

The East was in need of reorganization. In addition, Rome contended with the Parthian Empire for dominance of the Near East. The Parthian threat to the triumvirate's rule was urgent due to the fact that the Parthians supported the liberatores in the recent civil war, aid which included the supply of troops at Philippi.[100] As ruler of the East, Antony also assumed responsibility for overseeing Caesar's planned invasion of Parthia to avenge the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.

In 42 BC, the Roman East was composed of several directly controlled provinces and client kingdoms. The provinces included Macedonia, Asia, Bithynia, Cilicia, Cyprus, Syria, and Cyrenaica. Approximately half of the eastern territory was controlled by Rome's client kingdoms, nominally independent kingdoms subject to Roman direction. These kingdoms included:

- Odrysian Thrace in Eastern Europe

- The Bosporan Kingdom along the northern coast of the Black Sea

- Galatia, Pontus, Cappadocia, Armenia, and several smaller kingdoms in Asia Minor

- Judea, Commagene, and the Nabataean kingdom in the Middle East

- Ptolemaic Egypt in Africa

Activities in the East

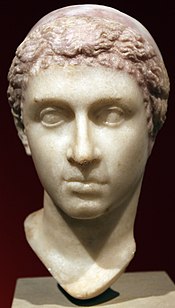

[edit]Right: bust of Cleopatra VII, dated 40–30 BC, Vatican Museums, showing her with a 'melon' hairstyle and Hellenistic royal diadem worn over her head

Antony spent the winter of 42 BC in Athens, where he ruled generously towards the Greek cities. A proclaimed philhellene ("Friend of all things Greek"), Antony supported Greek culture to win the loyalty of the inhabitants of the Greek East. He attended religious festivals and ceremonies, including initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries,[101] a secret cult dedicated to the worship of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. Beginning in 41 BC, he traveled across the Aegean Sea to Anatolia, leaving his friend Lucius Marcius Censorius as governor of Macedonia and Achaea. Upon his arrival in Ephesus in Asia, Antony was worshiped as the god Dionysus born anew.[102] He demanded heavy taxes from the Hellenic cities in return for his pro-Greek culture policies, but exempted those cities which had remained loyal to Caesar during the civil war and compensated those cities which had suffered under Caesar's assassins, including Rhodes, Lycia, and Tarsus. He granted pardons to all Roman nobles living in the East who had supported Pompey, except for Caesar's assassins.

Ruling from Ephesus, Antony consolidated Rome's hegemony in the East, receiving envoys from Rome's client kingdoms and intervening in their dynastic affairs, extracting enormous financial "gifts" from them in the process. Though King Deiotarus of Galatia supported Brutus and Cassius following Caesar's assassination, Antony allowed him to retain his position. He also confirmed Ariarathes X as king of Cappadocia after the execution of his brother Ariobarzanes III of Cappadocia by Cassius before the Battle of Philippi. In Hasmonean Judea, several Israelite delegations complained to Antony of the harsh rule of Phasael and Herod, the sons of Rome's assassinated chief minister in the territory of Judaea, who was an Edomite called Antipater the Idumaean. After Herod offered him a large financial gift, Antony confirmed the brothers in their positions. Subsequently, influenced by the beauty and charms of Glaphyra, the widow of Archelaüs (formerly the high priest of Comana), Antony deposed Ariarathes X, and appointed Glaphyra's son, Archelaüs, to rule Cappadocia.[103]

In October 41, Antony requested Rome's chief eastern vassal, the queen of Ptolemaic Egypt Cleopatra, meet him at Tarsus in Cilicia. Antony had first met a young Cleopatra while campaigning in Egypt in 55 BC and again in 48 BC when Caesar had backed her as queen of Egypt over the claims of her half-sister Arsinoe. Cleopatra would bear Caesar a son, Caesarion, in 47 BC and the two were living in Rome as Caesar's guests until his assassination in 44 BC. After Caesar's assassination, Cleopatra and Caesarion returned to Egypt, where she named the child as her co-ruler. In 42 BC, the Triumvirate, in recognition for Cleopatra's help towards Publius Cornelius Dolabella in opposition to the Liberators, granted official recognition to Caesarion's position as king of Egypt. Arriving in Tarsus aboard her magnificent ship, Cleopatra invited Antony to a grand banquet to solidify their alliance.[note 5] As the most powerful of Rome's eastern vassals, Egypt was indispensable in Rome's planned military invasion of the Parthian Empire. At Cleopatra's request, Antony ordered the execution of Arsinoe, who, though marched in Caesar's triumphal parade in 46 BC,[104] had been granted sanctuary at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Antony and Cleopatra then spent the winter of 41 BC together in Alexandria. Cleopatra bore Antony twin children, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, in 40 BC, and a third, Ptolemy Philadelphus, in 36 BC. Antony also granted formal control over Cyprus, which had been under Egyptian control since 47 BC during the turmoil of Caesar's civil war, to Cleopatra in 40 BC as a gift for her loyalty to Rome.[105]

Antony, in his first months in the East, raised money, reorganized his troops, and secured the alliance of Rome's client kingdoms. He also promoted himself as Hellenistic ruler, which won him the affection of the Greek peoples of the East but also made him the target of Octavian's propaganda in Rome. According to some ancient authors, Antony led a carefree life of luxury in Alexandria.[106][107] Upon learning the Parthian Empire had invaded Rome's territory in early 40 BC, Antony left Egypt for Syria to confront the invasion. However, after a short stay in Tyre, he was forced to sail with his army to Italy to confront Octavian due to Octavian's war against Antony's wife and brother.

Fulvia's civil war

[edit]Following the defeat of Brutus and Cassius, while Antony was stationed in the East, Octavian had authority over the West.[note 6] Octavian's chief responsibility was distributing land to tens of thousands of Caesar's veterans who had fought for the Triumvirate. Additionally, tens of thousands of veterans who had fought for the Republican cause in the war also required land grants. This was necessary to ensure they would not support a political opponent of the triumvirate.[108] However, the triumvirs did not possess sufficient state-controlled land to allot to the veterans. This left Octavian with two options: alienating many Roman citizens by confiscating their land, or alienating many Roman soldiers who might back a military rebellion against the triumvirate's rule. Octavian chose the former.[109] As many as eighteen Roman towns through Italy were affected by the confiscations of 41 BC, with entire populations driven out.[110]

Led by Fulvia, the wife of Antony, the senators grew hostile towards Octavian over the issue of the land confiscations. According to the ancient historian Cassius Dio, Fulvia was the most powerful woman in Rome at the time.[111] According to Dio, while Publius Servilius Vatia and Lucius Antonius were the consuls for the year 41 BC, real power was vested in Fulvia. As the mother-in-law of Octavian and the wife of Antony, no action was taken by the senate without her support.[112] Fearing Octavian's land grants would cause the loyalty of the Caesarian veterans to shift away from Antony, Fulvia traveled constantly with her children to the new veteran settlements in order to remind the veterans of their debt to Antony.[113][114] Fulvia also attempted to delay the land settlements until Antony returned to Rome, so that he could share credit for the settlements. With the help of Antony's brother, the consul of 41 BC Lucius Antonius, Fulvia encouraged the senate to oppose Octavian's land policies.

The conflict between Octavian and Fulvia caused great political and social unrest throughout Italy. Tensions escalated into open war, however, when Octavian divorced Claudia, Fulvia's daughter from her first husband Publius Clodius Pulcher. Outraged, Fulvia, supported by Lucius, raised an army to fight for Antony's rights against Octavian. According to the ancient historian Appian, Fulvia's chief reason for the war was her jealousy of Antony's affairs with Cleopatra in Egypt and desire to draw Antony back to Rome.[114] Lucius and Fulvia took a political and martial gamble in opposing Octavian and Lepidus, however, as the Roman army still depended on the triumvirs for their salaries.[110] Lucius and Fulvia, supported by their army, marched on Rome and promised the people an end to the triumvirate in favor of Antony's sole rule. However, when Octavian returned to the city with his army, the pair were forced to retreat to Perusia in Etruria. Octavian placed the city under siege while Lucius waited for Antony's legions in Gaul to come to his aid.[115][112] Away in the East and embarrassed by Fulvia's actions, Antony gave no instructions to his legions.[116][note 7] Without reinforcements, Lucius and Fulvia were forced to surrender in February 40 BC. While Octavian pardoned Lucius for his role in the war and even granted him command in Spain as his chief lieutenant there, Fulvia was forced to flee to Greece with her children. With the war over, Octavian was left in sole control over Italy. When Antony's governor of Gaul died, Octavian took over his legions there, further strengthening his control over the West.[117]

Despite the Parthian Empire's invasion of Rome's eastern territories, Fulvia's civil war forced Antony to leave the East and return to Rome in order to secure his position. Meeting her in Athens, Antony rebuked Fulvia for her actions before sailing on to Italy with his army to face Octavian, laying siege to Brundisium. This new conflict proved untenable for both Octavian and Antony, however. Their centurions, who had become important figures politically, refused to fight due to their shared service under Caesar. The legions under their command followed suit.[118][119] Meanwhile, in Sicyon, Fulvia died of a sudden and unknown illness.[120] Fulvia's death and the mutiny of their soldiers allowed the triumvirs to effect a reconciliation through a new power-sharing agreement in September 40 BC. The Roman world was redivided, with Antony receiving the Eastern provinces, Octavian the Western provinces, and Lepidus retained his junior position as governor of Africa. This agreement, known as the Treaty of Brundisium, reinforced the triumvirate and allowed Antony to begin preparing for Caesar's long-awaited campaign against the Parthian Empire. As a symbol of their renewed alliance, Antony married Octavia, Octavian's sister, in October 40 BC.

Antony's Parthian War

[edit]Roman–Parthian relations

[edit]

The rise of the Parthian Empire in the 3rd century BC and Rome's expansion into the Eastern Mediterranean during the 2nd century BC brought the two powers into direct contact, causing centuries of tumultuous and strained relations. Though periods of peace developed cultural and commercial exchanges, war was a constant threat. Influence over the buffer state of the Kingdom of Armenia, located to the north-east of Roman Syria, was often a central issue in the Roman-Parthian conflict. In 95 BC, Tigranes the Great, a Parthian ally, became king. Tigranes would later aid Mithradates of Pontus against Rome before being decisively defeated by Pompey in 66 BC.[121] Thereafter, with his son Artavasdes in Rome as a hostage, Tigranes would rule Armenia as an ally of Rome until his death in 55 BC. Rome then released Artavasdes, who succeeded his father as king.

In 53 BC, Rome's governor of Syria, Marcus Licinius Crassus, led an expedition across the Euphrates River into Parthian territory to confront the Parthian Shah Orodes II. Artavasdes II offered Crassus the aid of nearly forty thousand troops to assist his Parthian expedition on the condition that Crassus invade through Armenia as the safer route.[122] Crassus refused, choosing instead the more direct route by crossing the Euphrates directly into desert Parthian territory. Crassus' actions proved disastrous as his army was defeated at the Battle of Carrhae by a numerically inferior Parthian force. Crassus' defeat forced Armenia to shift its loyalty to Parthia, with Artavasdes II's sister marrying Orodes' son and heir Pacorus.[123]

In early 44 BC, Julius Caesar announced his intentions to invade Parthia and restore Roman power in the East. His reasons were to punish the Parthians for assisting Pompey in the recent civil war, to avenge Crassus' defeat at Carrhae, and especially to match the glory of Alexander the Great for himself.[124] Before Caesar could launch his campaign, however, he was assassinated. As part of the compromise between Antony and the Republicans to restore order following Caesar's murder, Publius Cornelius Dolabella was assigned the governorship of Syria and command over Caesar's planned Parthian campaign. The compromise did not hold, however, and the republicans were forced to flee to the East. The republicans directed Quintus Labienus to attract the Parthians to their side in the resulting war against Antony and Octavian. After the liberatores were defeated at the Battle of Philippi, Labienus joined the Parthians.[125][126] Despite Rome's internal turmoil during the time, the Parthians did not immediately benefit from the power vacuum in the East due to Orodes II's reluctance despite Labienus' urgings to the contrary.[127]

In the summer of 41 BC, Antony, to reassert Roman power in the East, conquered Palmyra on the Roman-Parthian border.[127] Antony then spent the winter of 41 BC in Alexandria with Cleopatra, leaving only two legions to defend the Syrian border against Parthian incursions. The legions, however, were composed of former Republican troops and Labienus convinced Orodes II to invade.

Parthian Invasion

[edit]

A Parthian army, led by Orodes II's eldest son Pacorus, invaded Syria in early 40 BC. Labienus, the Republican ally of Brutus and Cassius, accompanied him to advise him and to rally the former Republican soldiers stationed in Syria to the Parthian cause. Labienus recruited many of the former Republican soldiers to the Parthian campaign in opposition to Antony. The joint Parthian–Roman force, after initial success in Syria, separated to lead their offensive in two directions: Pacorus marched south toward Hasmonean Judea while Labienus crossed the Taurus Mountains to the north into Cilicia. Labienus conquered southern Anatolia with little resistance. The Roman governor of Asia, Lucius Munatius Plancus, a partisan of Antony, was forced to flee his province, allowing Labienus to recruit the Roman soldiers stationed there. For his part, Pacorus advanced south to Phoenicia and Palestine. In Hasmonean Judea, the exiled prince Antigonus allied himself with the Parthians. When his brother, Rome's client king Hyrcanus II, refused to accept Parthian domination, he was deposed in favor of Antigonus as Parthia's client king in Judea. Pacorus' conquest had captured much of the Syrian and Palestinian interior, with much of the Phoenician coast occupied as well. The city of Tyre remained the last major Roman outpost in the region.[128]

Antony, then in Egypt with Cleopatra, did not respond immediately to the Parthian invasion. Though he left Alexandria for Tyre in early 40 BC, when he learned of the civil war between his wife and Octavian, he was forced to return to Italy with his army to secure his position in Rome rather than defeat the Parthians.[128] Instead, Antony dispatched Publius Ventidius Bassus to check the Parthian advance. Arriving in the East in spring 39 BC, Ventidius surprised Labienus near the Taurus Mountains, claiming victory at the Cilician Gates. Ventidius ordered Labienus executed as a traitor and the formerly rebellious Roman soldiers under his command were reincorporated under Antony's control. He then met a Parthian army at the border between Cilicia and Syria, defeating it and killing a large portion of the Parthian soldiers at the Amanus Pass. Ventidius' actions temporarily halted the Parthian advance and restored Roman authority in the East, forcing Pacorus to abandon his conquests and return to Parthia.[129]

In the spring of 38 BC, the Parthians resumed their offensive with Pacorus leading an army across the Euphrates. Ventidius, in order to gain time, leaked disinformation to Pacorus implying that he should cross the Euphrates River at their usual ford. Pacorus did not trust this information and decided to cross the river much farther downstream; this was what Ventidius hoped would occur and gave him time to get his forces ready.[130] The Parthians faced no opposition and proceeded to the town of Gindarus in Cyrrhestica where Ventidius' army was waiting. At the Battle of Cyrrhestica, Ventidius inflicted an overwhelming defeat against the Parthians which resulted in the death of Pacorus. Overall, the Roman army had achieved a complete victory with Ventidius' three successive victories forcing the Parthians back across the Euphrates.[131] Pacorus' death threw the Parthian Empire into chaos. Shah Orodes II, overwhelmed by the grief of his son's death, appointed his younger son Phraates IV as his successor. However, Phraates IV assassinated Orodes II in late 38 BC, succeeding him on the throne.[132][133]

Ventidius feared Antony's wrath if he invaded Parthian territory, thereby stealing his glory; so instead he attacked and subdued the eastern kingdoms, which had revolted against Roman control following the disastrous defeat of Crassus at Carrhae.[134] One such rebel was King Antiochus of Commagene, whom he besieged in Samosata. Antiochus tried to make peace with Ventidius, but Ventidius told him to approach Antony directly. After peace was concluded, Antony sent Ventidius back to Rome where he celebrated a triumph, the first Roman to triumph over the Parthians.[note 8]

Conflict with Sextus Pompey

[edit]

While Antony and the other triumvirs ratified the Treaty of Brundisium to redivide the Roman world among themselves, the rebel Sextus Pompey, the son of Caesar's rival Pompey the Great, was largely ignored. From his stronghold on Sicily, he continued his piratical activities across Italy and blocked the shipment of grain to Rome. The lack of food in Rome undermined the triumvirate's political support. This pressure forced the triumvirs to meet with Sextus in early 39 BC.[135]

While Octavian wanted an end to the ongoing blockade of Italy, Antony sought peace in the West in order to make the Triumvirate's legions available for his service in his planned campaign against the Parthians. Though the Triumvirs rejected Sextus' initial request to replace Lepidus as the third man in the triumvirate, they did grant other concessions. Under the terms of the Treaty of Misenum, Sextus was allowed to retain control over Sicily and Sardinia, with the provinces of Corsica and Greece being added to his territory. He was also promised a future position with the Priestly College of Augurs and the consulship for 35 BC. In exchange, Sextus agreed to end his naval blockade of Italy, supply Rome with grain, and halt his piracy of Roman merchant ships.[136] However, the most important provision of the Treaty was the end of the proscription the trimumvirate had begun in late 43 BC. Many of the proscribed senators, rather than face death, fled to Sicily seeking Sextus' protection. With the exception of those responsible for Caesar's assassination, all those proscribed were allowed to return to Rome and promised compensation. This caused Sextus to lose many valuable allies as the formerly exiled senators gradually aligned themselves with either Octavian or Antony. To secure the peace, Octavian betrothed Marcus Claudius Marcellus, Octavian's three-year-old nephew and Antony's stepson, to Sextus' daughter Pompeia.[137] With peace in the West secured, Antony planned to retaliate against Parthia. Under an agreement with Octavian, Antony would be supplied with extra troops for his campaign. With this military purpose on his mind, Antony sailed to Greece with Octavia, where he behaved in a most extravagant manner, assuming the attributes of the Greek god Dionysus in 39 BC.

The peace with Sextus was short-lived, however. When Sextus demanded control over Greece as the agreement provided, Antony demanded the province's tax revenues be to fund the Parthian campaign. Sextus refused.[138] Meanwhile, Sextus' admiral Menas betrayed him, shifting his loyalty to Octavian and thereby granting him control of Corsica, Sardinia, three of Sextus' legions, and a larger naval force. These actions worked to renew Sextus' blockade of Italy, preventing Octavian from sending the promised troops to Antony for the Parthian campaign. This new delay caused Antony to quarrel with Octavian, forcing Octavia to mediate a truce between them. Under the Treaty of Tarentum, Antony provided a large naval force for Octavian's use against Sextus while Octavian promised to raise new legions for Antony to support his invasion of Parthia.[139] As the term of the Triumvirate was set to expire at the end of 38 BC, the two unilaterally extended their term of office another five years until 33 BC without seeking approval of the senate or the assemblies. To seal the Treaty, Antony's elder son Marcus Antonius Antyllus, then only six years old, was betrothed to Octavian's only daughter Julia, then only an infant. With the Treaty signed, Antony returned to the East, leaving Octavia in Italy.

Reconquest of Judea

[edit]With Publius Ventidius Bassus returned to Rome in triumph for his defensive campaign against the Parthians, Antony appointed Gaius Sosius as the new governor of Syria and Cilicia in early 38 BC. Antony, still in the West negotiating with Octavian, ordered Sosius to depose Antigonus, who had been installed in the recent Parthian invasion as the ruler of Hasmonean Judea, and to make Herod the new Roman client king in the region. Years before in 40 BC, the Roman senate had proclaimed Herod "King of the Jews" because Herod had been a loyal supporter of Hyrcanus II, Rome's previous client king before the Parthian invasion, and was from a family with long standing connections to Rome.[140] The Romans hoped to use Herod as a bulwark against the Parthians in the coming campaign.[141]

Advancing south, Sosius captured the island-city of Aradus on the coast of Phoenicia by the end of 38 BC. The following year, the Romans besieged Jerusalem. After a forty-day siege, the Roman soldiers stormed the city and, despite Herod's pleas for restraint, acted without mercy, pillaging and killing all in their path, prompting Herod to complain to Antony.[142] Herod finally resorted to bribing Sosius and his troops in order that they would not leave him "king of a desert".[143] Antigonus was forced to surrender to Sosius, and was sent to Antony for the triumphal procession in Rome. Herod, however, fearing that Antigonus would win backing in Rome, bribed Antony to execute Antigonus. Antony, who recognized that Antigonus would remain a permanent threat to Herod, ordered him beheaded in Antioch. Now secure on his throne, Herod would rule the Herodian Kingdom until his death in 4 BC, and would be an ever-faithful client king of Rome.

Parthian Campaign

[edit]With the triumvirate renewed in 38 BC, Antony returned to Athens in the winter with his new wife Octavia, the sister of Octavian. With the assassination of the Parthian king Orodes II by his son Phraates IV, who then seized the Parthian throne, in late 38 BC, Antony prepared to invade Parthia himself.

Antony, however, realized Octavian had no intention of sending him the additional legions he had promised under the Treaty of Tarentum. To supplement his own armies, Antony instead looked to Rome's principal vassal in the East: his lover Cleopatra. In addition to significant financial resources, Cleopatra's backing of his Parthian campaign allowed Antony to amass the largest army Rome had ever assembled in the East. Wintering in Antioch during 37, Antony's combined Roman–Egyptian army numbered some 100,000, including 60,000 soldiers from sixteen legions, 10,000 cavalry from Spain and Gaul, plus an additional 30,000 auxiliaries.[144] The size of his army indicated Antony's intention to conquer Parthia, or at least receive its submission by capturing the Parthian capital of Ecbatana. Antony's rear was protected by Rome's client kingdoms in Anatolia, Syria, and Judea, while the client kingdoms of Cappadocia, Pontus, and Commagene would provide supplies along the march.

Antony's first target for his invasion was the Kingdom of Armenia. Ruled by King Artavasdes II of Armenia, Armenia had been an ally of Rome since the defeat of Tigranes the Great by Pompey the Great in 66 BC during the Third Mithridatic War. However, following Marcus Licinius Crassus's defeat at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, Armenia was forced into an alliance with Parthia due to Rome's weakened position in the East. Antony dispatched Publius Canidius Crassus to Armenia, receiving Artavasdes II's surrender without opposition. Canidius then led an invasion into the South Caucasus, subduing Iberia. There, Canidius forced the Iberian King Pharnavaz II into an alliance against Zober, king of neighboring Albania, subduing the kingdom and reducing it to a Roman protectorate.

With Armenia and the Caucasus secured, Antony marched south, crossing into the Parthian province of Media Atropatene. Though Antony desired a pitched battle, the Parthians would not engage, allowing Antony to march deep into Parthian territory by mid-August of 36 BC. This forced Antony to leave his logistics train in the care of two legions (approximately 10,000 soldiers), which was then attacked and completely destroyed by the Parthian army before Antony could rescue them. Though the Armenian King Artavasdes II and his cavalry were present during the massacre, they did not intervene. Despite the ambush, Antony continued the campaign. However, Antony was soon forced to retreat in mid-October after a failed two-month siege of the provincial capital.

The retreat soon proved a disaster as Antony's demoralized army faced increasing supply difficulties in the mountainous terrain during winter while constantly being harassed by the Parthian army. According to Plutarch, eighteen battles were fought between the retreating Romans and the Parthians during the month-long march back to Armenia, with approximately 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry dying during the retreat alone. Once in Armenia, Antony quickly marched back to Syria to protect his interests there by late 36 BC, losing an additional 8,000 soldiers along the way. In all, two-fifths of his original army (some 80,000 men) had died during his failed campaign.[145] The narration of Strabo and Plutarch blames the Armenian king for the defeat, but modern sources note Antony's poor management.[146]

Antony and Cleopatra

[edit]Meanwhile, in Rome, the triumvirate was no more. Octavian forced Lepidus to resign after the older triumvir attempted to take control of Sicily after the defeat of Sextus. Now in sole power, Octavian was occupied in wooing the aristocracy to his side. He married Livia and started to attack Antony. He argued that Antony was a man of low morals to have left his faithful wife abandoned in Rome with the children to be with the promiscuous queen of Egypt. Several times Antony was summoned to Rome, but remained in Alexandria with Cleopatra.[147]

Again with Egyptian money, Antony invaded Armenia, this time successfully. In the return, a mock Roman triumph was celebrated in the streets of Alexandria. The parade through the city was a pastiche of Rome's most important military celebration. For the finale, the whole city was summoned to hear a very important political statement. Surrounded by Cleopatra and her children, Antony ended his alliance with Octavian.

He distributed kingdoms among his children: Alexander Helios was named king of Armenia, Media and Parthia (territories which were not for the most part under the control of Rome), his twin Cleopatra Selene got Cyrenaica and Libya, and the young Ptolemy Philadelphus was awarded Syria and Cilicia. As for Cleopatra, she was proclaimed Queen of Kings and Queen of Egypt, to rule with Caesarion (Ptolemy XV Caesar, son of Cleopatra by Julius Caesar), King of Kings and King of Egypt. Most important of all, Caesarion was declared legitimate son and heir of Caesar. These proclamations were known as the Donations of Alexandria and caused a fatal breach in Antony's relations with Rome.

While the distribution of nations among Cleopatra's children was hardly a conciliatory gesture, it did not pose an immediate threat to Octavian's political position. Far more dangerous was the acknowledgment of Caesarion as legitimate and heir to Caesar's name. Octavian's base of power was his link with Caesar through adoption, which granted him much-needed popularity and loyalty of the legions. To see this convenient situation attacked by a child borne by the richest woman in the world was something Octavian could not accept. The triumvirate expired on the last day of 33 BC and was not renewed. Another civil war was beginning.

During 33 and 32 BC, a propaganda war was fought in the political arena of Rome, with accusations flying between sides. Antony (in Egypt) divorced Octavia and accused Octavian of being a social upstart, of usurping power, and of forging the adoption papers by Caesar. Octavian responded with treason charges: of illegally keeping provinces that should be given to other men by lots, as was Rome's tradition, and of starting wars against foreign nations (Armenia and Parthia) without the consent of the senate.

Antony was also held responsible for Sextus Pompey's execution without a trial. In 32 BC, the senate deprived him of his powers and declared war against Cleopatra – not Antony, because Octavian had no wish to advertise his role in perpetuating Rome's internecine bloodshed. Octavian and other Roman Senators believed that turning the hostilities towards Cleopatra as the villain would gather the most support from Romans for war. Contributing to this would be the years of propaganda against Cleopatra published by the Romans, dating back to the days of Julius Caesar. Octavian, informed of Antony's will by two Antonian defectors, sacrilegiously raided the Temple of Vesta to secure it. The will, which some modern scholars have suggested was partially forged – largely on legal grounds – is never so described in the ancient sources. Octavian's publication of the will's provisions, which named Antony and Cleopatra's children as heirs and directed his burial in Alexandria, was used as a political weapon in Rome to declare war against Cleopatra and Egypt as a whole.[148] This was the perfect summation of their attacks on the woman Antony loved and they believed threatened their republic. Both consuls, Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Gaius Sosius (both Antony's men), and a third of the senate abandoned Rome to meet Antony and Cleopatra in Greece.

In 31 BC, the war started. Octavian's general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa captured the Greek city and naval port of Methone, loyal to Antony. The enormous popularity of Octavian with the legions secured the defection of the provinces of Cyrenaica and Greece to his side. On 2 September, the naval Battle of Actium took place. Antony and Cleopatra's navy was overwhelmed, and they were forced to escape to Egypt with 60 ships.

Death

[edit]

Octavian, now close to absolute power, invaded Egypt with Agrippa in August of 30 BC. With no other refuge to escape to, Antony stabbed himself with his sword in the mistaken belief that Cleopatra had already done so. When he found out that Cleopatra was still alive, his friends brought him to Cleopatra's monument in which she was hiding, and he died in her arms.

Cleopatra was allowed to conduct Antony's burial rites after she had been captured by Octavian. Realising that she was destined for Octavian's triumph in Rome, she made several attempts to take her life and finally succeeded in mid-August. Octavian had Caesarion and Antyllus killed, but he spared Iullus as well as Antony's children by Cleopatra, who were paraded through the streets of Rome.

Aftermath and legacy

[edit]Cicero's son, Cicero Minor, announced Antony's death to the senate.[151] Antony's honours were revoked and his statues removed,[152] but he was not subject to a complete damnatio memoriae.[153] Cicero's son also made a decree that no member of the Antonii would ever bear the name Marcus again.[154] "In this way Heaven entrusted the family of Cicero the final acts in the punishment of Antony."[155]

When Antony died, Octavian became uncontested ruler of Rome. In the following years, Octavian, who was known as Augustus after 27 BC, managed to accumulate in his person all administrative, political, and military offices. When Augustus died in AD 14, his political powers passed to his adopted son Tiberius; the Roman Empire had begun.

The rise of Caesar and the subsequent civil war between his two most powerful adherents effectively ended the credibility of the Roman oligarchy as a governing power and ensured that all future power struggles would centre upon which one individual would achieve supreme control of the government, eliminating the senate and the former magisterial structure as important foci of power in these conflicts. Thus, in history, Antony appears as one of Caesar's main adherents, he and Octavian being the two men around whom power coalesced following the assassination of Caesar, and finally as one of the three men chiefly responsible for the demise of the republic.[156]

Marriages and issue

[edit]

Antony had many mistresses (including Cytheris) and was married in succession to Fadia, Antonia, Fulvia, Octavia and Cleopatra. He left a number of children.[157][158] Through his daughters by Octavia, he would be ancestor to the Roman emperors Caligula, Claudius and Nero.

- Marriage to Fadia, a daughter of a freedman. According to Cicero, Fadia bore Antony several children. Nothing is known about Fadia or their children. Cicero is the only Roman source that mentions Antony's first wife.

- Marriage to first paternal cousin Antonia Hybrida Minor, daughter of Gaius Antonius Hybrida. According to Plutarch, Antony threw her out of his house in Rome because she slept with his friend, the tribune Publius Cornelius Dolabella. This occurred by 47 BC and Antony divorced her. By Antonia, he had a daughter:

- Antonia, married the wealthy Greek Pythodoros of Tralles.

- Marriage to Fulvia, by whom he had two sons:

- Marcus Antonius Antyllus, murdered by Octavian in 30 BC.

- Iullus Antonius, married Claudia Marcella the Elder, daughter of Octavia.

- Marriage to Octavia the Younger, sister of Octavian, later emperor Augustus; they had two daughters:

- Antonia the Elder married Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (consul 16 BC); maternal grandmother of the Empress Valeria Messalina and paternal grandmother of the emperor Nero.

- Antonia the Younger married Nero Claudius Drusus, the younger son of the Empress Livia Drusilla and brother of the emperor Tiberius; mother of the emperor Claudius, paternal grandmother of the emperor Caligula and empress Agrippina the Younger, and maternal great-grandmother of the emperor Nero.

- Children with the Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt, the former lover of Julius Caesar:

- Alexander Helios

- Cleopatra Selene II, married King Juba II of Numidia and later Mauretania; the queen of Syria, Zenobia of Palmyra, was reportedly descended from Selene and Juba II.

- Ptolemy Philadelphus.

Descendants

[edit]Through his daughters by Octavia, he was the paternal great grandfather of Roman emperor Caligula, the maternal grandfather of emperor Claudius, and both maternal great-great-grandfather and paternal great-great uncle of the emperor Nero of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Through his eldest daughter, he was ancestor to the long line of kings and co-rulers of the Bosporan Kingdom, the longest-living Roman client kingdom, as well as the rulers and royalty of several other Roman client states. Through his daughter by Cleopatra, Antony was ancestor to the royal family of Mauretania, another Roman client kingdom, while through his sole surviving son Iullus, he was ancestor to several famous Roman statesmen.

- 1. Antonia, born 50 BC, had 1 child

- A. Pythodorida of Pontus, 30 BC or 29 BC – 38 AD, had 3 children

- I. Artaxias III, King of Armenia, 13 BC – 35 AD, died without issue

- II. Polemon II, King of Pontus, 12 BC or 11 BC – 74 AD, died without issue

- III. Antonia Tryphaena, Queen of Thrace, 10 BC – 55 AD, had 4 children

- a. Rhoemetalces II, King of Thrace, died 38 AD, died without issue

- b. Gepaepyris, Queen of the Bosporan Kingdom, had 2 children

- i. Tiberius Julius Mithridates, King of the Bosporan Kingdom, died 68 AD, died without issue