Semiperimeter

In geometry, the semiperimeter of a polygon is half its perimeter. Although it has such a simple derivation from the perimeter, the semiperimeter appears frequently enough in formulas for triangles and other figures that it is given a separate name. When the semiperimeter occurs as part of a formula, it is typically denoted by the letter s.

Motivation: triangles

[edit]

The semiperimeter is used most often for triangles; the formula for the semiperimeter of a triangle with side lengths a, b, c

Properties

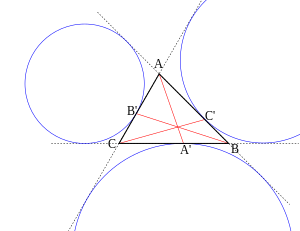

[edit]In any triangle, any vertex and the point where the opposite excircle touches the triangle partition the triangle's perimeter into two equal lengths, thus creating two paths each of which has a length equal to the semiperimeter. If A, B, B', C' are as shown in the figure, then the segments connecting a vertex with the opposite excircle tangency (AA', BB', CC', shown in red in the diagram) are known as splitters, and

The three splitters concur at the Nagel point of the triangle.

A cleaver of a triangle is a line segment that bisects the perimeter of the triangle and has one endpoint at the midpoint of one of the three sides. So any cleaver, like any splitter, divides the triangle into two paths each of whose length equals the semiperimeter. The three cleavers concur at the center of the Spieker circle, which is the incircle of the medial triangle; the Spieker center is the center of mass of all the points on the triangle's edges.

A line through the triangle's incenter bisects the perimeter if and only if it also bisects the area.

A triangle's semiperimeter equals the perimeter of its medial triangle.

By the triangle inequality, the longest side length of a triangle is less than the semiperimeter.

Formulas involving the semiperimeter

[edit]For triangles

[edit]The area A of any triangle is the product of its inradius (the radius of its inscribed circle) and its semiperimeter:

The area of a triangle can also be calculated from its semiperimeter and side lengths a, b, c using Heron's formula:

The circumradius R of a triangle can also be calculated from the semiperimeter and side lengths:

This formula can be derived from the law of sines.

The inradius is

The law of cotangents gives the cotangents of the half-angles at the vertices of a triangle in terms of the semiperimeter, the sides, and the inradius.

The length of the internal bisector of the angle opposite the side of length a is[1]

In a right triangle, the radius of the excircle on the hypotenuse equals the semiperimeter. The semiperimeter is the sum of the inradius and twice the circumradius. The area of the right triangle is where a, b are the legs.

For quadrilaterals

[edit]The formula for the semiperimeter of a quadrilateral with side lengths a, b, c, d is

One of the triangle area formulas involving the semiperimeter also applies to tangential quadrilaterals, which have an incircle and in which (according to Pitot's theorem) pairs of opposite sides have lengths summing to the semiperimeter—namely, the area is the product of the inradius and the semiperimeter:

The simplest form of Brahmagupta's formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral has a form similar to that of Heron's formula for the triangle area:

Bretschneider's formula generalizes this to all convex quadrilaterals:

in which α and γ are two opposite angles.

The four sides of a bicentric quadrilateral are the four solutions of a quartic equation parametrized by the semiperimeter, the inradius, and the circumradius.

Regular polygons

[edit]The area of a convex regular polygon is the product of its semiperimeter and its apothem.

Circles

[edit]The semiperimeter of a circle, also called the semicircumference, is directly proportional to its radius r:

The constant of proportionality is the number pi, π.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, Roger A. (2007). Advanced Euclidean Geometry. Mineola, New York: Dover. p. 70. ISBN 9780486462370.