Charles Boycott

Charles Boycott | |

|---|---|

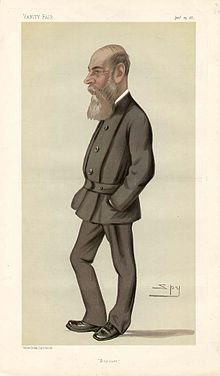

Boycott as caricatured by Spy (Leslie Ward) in Vanity Fair, January 1881 | |

| Born | Charles Cunningham Boycatt 12 March 1832[citation needed] Burgh St Peter, Norfolk, England |

| Died | 19 June 1897 (aged 65) |

| Resting place | Burgh St Peter |

| Occupations |

|

| Employers | |

| Opponent | Irish National Land League |

| Spouse |

Anne Boycott (m. 1852) |

Charles Cunningham Boycott (12 March 1832 – 19 June 1897) was an English land agent whose ostracism by his local community in Ireland gave the English language the term boycott. He had served in the British Army 39th Foot, which brought him to Ireland. After retiring from the army, Boycott worked as a land agent for Lord Erne, a landowner in the Lough Mask area of County Mayo.[1]

In 1880, as part of its campaign for the Three Fs (fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale) and specifically in resistance to proposed evictions on the estate, local activists of the Irish National Land League encouraged Boycott's employees (including the seasonal workers required to harvest the crops on Lord Erne's estate) to withdraw their labour, and began a campaign of isolation against Boycott in the local community. This campaign included shops in nearby Ballinrobe refusing to serve him, and the withdrawal of services. Some were threatened with violence to ensure compliance.

Opposition to the campaign against Boycott became a cause célèbre in the British press after he wrote a letter to The Times. Newspapers sent correspondents to the West of Ireland to highlight what they viewed as the victimisation of a servant of a peer of the realm by Irish nationalists. Fifty Orangemen from County Cavan and County Monaghan travelled to Lord Erne's estate to harvest the crops, while a regiment of the 19th Royal Hussars and more than 1,000 men of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were deployed to protect the harvesters. The episode was estimated to have cost the British government and others at least £10,000 to harvest about £500 worth of crops.

Boycott left Ireland on 1 December 1880, and in 1886, became land agent for Hugh Adair's Flixton estate in Suffolk. He died at the age of 65 on 19 June 1897 in his home in Flixton, after an illness earlier that year.

Early life and family

[edit]

Charles Cunningham Boycott was born in 1832 to Reverend William Boycatt and his wife Georgiana.[2] He grew up in the village of Burgh St Peter in Norfolk, England;[2] the Boycatt family had lived in Norfolk for almost 150 years.[3] They were of Huguenot origin, and had fled from France in 1685 when Louis XIV revoked civil and religious liberties to French Protestants.[3] Charles Boycott was named Boycatt in his baptismal records. The family changed the spelling of its name from Boycatt to Boycott in 1841.[3]

Boycott was educated at a boarding school in Blackheath, London.[4] He was interested in the military—and in 1848, entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, in hopes of serving in the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners.[4] He was discharged from the academy in 1849 after failing a periodic exam,[4] and the following year his family bought him a commission in the 39th Foot regiment for £450.[4][5]

Boycott's regiment transferred to Belfast shortly after his arrival.[6] Six months later, it was sent to Newry before marching to Dublin, where it remained for a year.[6] In 1852, Boycott married Anne Dunne in St Paul's Church, Arran Quay, Dublin.[6] He was ill between August 1851 and February 1852 and sold his commission the following year,[6] but decided to remain in Ireland. He leased a farm in County Tipperary, where he acted as a landlord on a small scale.[7]

Life on Achill Island

[edit]

After receiving an inheritance, Boycott was persuaded by his friend, Murray McGregor Blacker, a local magistrate, to move to Achill Island, a large island off the coast of County Mayo.[8] McGregor Blacker agreed to sublet 2,000 acres (809 ha) of land belonging to the Irish Church Mission Society on Achill to Boycott, who moved there in 1854.[8] According to Joyce Marlow in the book Captain Boycott and the Irish, Boycott's life on the island was difficult initially, and in Boycott's own words it was only after "a long struggle against adverse circumstances" that he became prosperous.[8] With money from another inheritance and profits from farming, he built a large house near Dooagh.[8][9]

Boycott was involved in a number of disputes while on Achill.[8] Two years after his arrival, he was unsuccessfully sued for assault by Thomas Clarke, a local man.[8] Clarke said that he had gone to Boycott's house because Boycott owed him money.[8] He said that he had asked for repayment of the debt, and that Boycott had refused to pay him and told him to go away, which Clarke refused to do.[8] Clarke alleged that Boycott approached him and said: "If you do not be off, I will make you."[8] Clarke later withdrew his allegations, and said that Boycott did not actually owe him any money.[8]

Both Boycott and McGregor Blacker were involved in a protracted dispute with Mr Carr, the agent for the Achill Church Mission Estate, from whom McGregor Blacker leased the lands, and Mr O'Donnell, Carr's bailiff.[8] The dispute began when Boycott and Carr supported different sets of candidates in elections for the Board of Guardians to the Church Mission Estate, and Boycott's candidates won.[8] Carr was also the local receiver of wrecks, which meant that he was entitled to collect the salvage from all shipwrecks in the area, and guard it until it was sold in a public auction.[8] The local receiver had a right to a percentage of the sale and to keep whatever did not sell.[8] In 1860 Carr wrote a letter to the Official Receiver of Wrecks stating that Boycott and his men had illegally broken up a wreck and moved the salvage to Boycott's property.[8] In response to this accusation, Boycott sued Carr for libel and claimed £500 in damages.[8]

Life in Lough Mask before controversy

[edit]

In 1873, Boycott moved to Lough Mask House, owned by Lord Erne, four miles (6 km) from Ballinrobe in County Mayo.[10] The 3rd Earl of Erne was a wealthy Ulster landowner who lived at Crom Castle, a country house near Newtownbutler in the south-east of County Fermanagh.[11] He owned 40,386 acres (163.44 km2) of land in Ireland, of which 31,389 were in County Fermanagh, 4,826 in County Donegal, 1,996 in County Sligo, and 2,184 in County Mayo.[11] Lord Erne also owned properties in Dublin.[11]

Boycott agreed to be Lord Erne's agent for 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) he owned in County Mayo. One of Boycott's responsibilities was to collect rents from tenant farmers on the land,[10] for which he earned ten per cent of the total rent due to Lord Erne, which was £500 each year.[10] In his roles as farmer and agent, Boycott employed numerous local people as labourers, grooms, coachmen, and house-servants.[10] Joyce Marlow wrote that Boycott had become set in his mode of thought, and that his twenty years on Achill had "...strengthened his innate belief in the divine right of the masters, and the tendency to behave as he saw fit, without regard to other people's point of view or feelings."[10]

During his time in Lough Mask before the controversy began, Boycott had become unpopular with the tenants.[10] He had become a magistrate and was an Englishman, which may have contributed to his unpopularity,[10] but according to Marlow it was due more to his personal temperament.[10] While Boycott himself maintained that he was on good terms with his tenants, they said that he had laid down many petty restrictions, such as not allowing gates to be left open and not allowing hens to trespass on his property, and that he fined anyone who transgressed these restrictions.[10] He had also withdrawn privileges from the tenants, such as collecting wood from the estate.[10] In August 1880, his labourers went on strike in a dispute over a wage increase.[12]

Lough Mask affair

[edit]Historical background

[edit]

In the nineteenth century, agriculture was the biggest industry in Ireland.[13] In 1876, the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland commissioned a survey to find who owned the land in Ireland. The survey found that almost all land was the property of just 10,000 people, or 0.2 per cent of the population.[13] The majority were small landlords, but the 750 richest landlords owned half of the country between them.[13] Many of the richest were absentee landlords who lived in Britain or elsewhere in Ireland, and paid agents like Charles Boycott to manage their estates.[13]

Landlords generally divided their estates into smaller farms that they rented to tenant farmers.[13] Tenant farmers were generally on one-year leases, and could be evicted even if they paid their rents.[13] Some of the tenants were large farmers who farmed over 100 acres (0.40 km2), but the majority were much smaller—on average between 15 and 50 acres (0.06–0.20 km2).[13] Many small farmers worked as labourers on the larger farms.[13] The poorest agricultural workers were the landless labourers, who worked on the land of other farmers.[13] Farmers were an important group politically, having more votes than any other sector of society.[13]

In the 1850s, some tenant farmers formed associations to demand the three Fs: fair rent, fixity of tenure, and free sale.[14] In the 1870s, the Fenians tried to organise the tenant farmers in County Mayo to resist eviction.[14] They mounted a demonstration against a local landlord in Irishtown and succeeded in getting him to lower his rents.[14]

Michael Davitt was the son of a small tenant farmer in County Mayo who became a journalist and joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). He was arrested and given a 15-year sentence for gun-running.[14] Charles Stewart Parnell, then Member of Parliament for Meath and member of the Home Rule League, arranged to have Davitt released on probation. When Davitt returned to County Mayo, he was impressed by the Fenians' attempts to organise farmers. He thought that the "land question" was the best way to get the support of the farmers for Irish independence.[14]

In October 1879, after forming the Land League of Mayo, Davitt formed the Irish National Land League. The Land League's aims were to reduce rents and to stop evictions, and in the long term, to make tenant farmers owners of the land they farmed. Davitt asked Parnell to become the leader of the league. In 1880, Parnell was also elected leader of the Home Rule Party.[14]

Parnell's speech in Ennis

[edit]On 19 September 1880, Parnell gave a speech in Ennis, County Clare, to a crowd of Land League members.[15] He asked the crowd, "What do you do with a tenant who bids for a farm from which his neighbour has been evicted?"[15] The crowd responded, "kill him", "shoot him".[15] Parnell replied:[16]

I wish to point out to you a very much better way – a more Christian and charitable way, which will give the lost man an opportunity of repenting. When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him – you must shun him in the streets of the town – you must shun him in the shop – you must shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry,[note 1] by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he committed.

This speech set out the Land League's powerful weapon of social ostracism, which was first used against Charles Boycott.[15]

Community action

[edit]The Land League was very active in the Lough Mask area, and one of the local leaders, Father John O'Malley, had been involved in the labourer's strike in August 1880.[12] The following month, Lord Erne's tenants were due to pay their rents.[12] He had agreed to a 10 per cent reduction owing to a poor harvest, but all except two of his tenants demanded a 25 per cent reduction.[12] Boycott said that he had written to Lord Erne, and that Erne had refused to accede to the tenants' demands.[12] He then issued demands for the outstanding rents, and obtained eviction notices against eleven tenants.[12]

Three days after Parnell's speech in Ennis, a process server and seventeen members of the RIC began the attempt to serve Boycott's eviction notices.[12] Legally, they had to be delivered to the head of the household or his spouse within a certain time period. The process server successfully delivered notices to three of the tenants, but a fourth, Mrs Fitzmorris, refused to accept the notice and began waving a red flag to alert other tenants that the notices were being served.[12] The women of the area descended on the process server and the constabulary, and began throwing stones, mud, and manure at them, succeeding in driving them away to seek refuge in Lough Mask House.[12]

The process server tried unsuccessfully to serve the notices the following day.[12] News soon spread to nearby Ballinrobe, from where many people descended on Lough Mask House, where, according to journalist James Redpath, they advised Boycott's servants and labourers to leave his employment immediately.[12] Boycott said that many of his servants were forced to leave "under threat of ulterior consequences".[12] Martin Branigan, a labourer who subsequently sued Boycott for non-payment of wages, claimed he left because he was afraid of the people who came into the field where he was working.[12] Eventually, all Boycott's employees left, forcing him to run the estate without help.[12]

Within days, the blacksmith, postman, and laundress were persuaded or volunteered to stop serving Boycott.[12] Boycott's young nephew volunteered to act as postman, but he was intercepted en route between Ballinrobe and Lough Mask, and told that he would be in danger if he continued.[12] Soon, shopkeepers in Ballinrobe stopped serving Boycott, and he had to bring food and other provisions by boat from Cong.[12]

Newspaper coverage

[edit]Before October 1880, Boycott's situation was little known outside County Mayo.[17] On 14 October of that year, Boycott wrote a letter to The Times about his situation:[17]

THE STATE OF IRELAND

Sir, The following detail may be interesting to your readers as exemplifying the power of the Land League. On the 22nd September a process-server, escorted by a police force of seventeen men, retreated to my house for protection, followed by a howling mob of people, who yelled and hooted at the members of my family. On the ensuing day, September 23rd, the people collected in crowds upon my farm, and some hundred or so came up to my house and ordered off, under threats of ulterior consequences, all my farm labourers, workmen, and stablemen, commanding them never to work for me again. My herd has been frightened by them into giving up his employment, though he has refused to give up the house he held from me as part of his emolument. Another herd on an off farm has also been compelled to resign his situation. My blacksmith has received a letter threatening him with murder if he does any more work for me, and my laundress has also been ordered to give up my washing. A little boy, twelve years of age, who carried my post-bag to and from the neighbouring town of Ballinrobe, was struck and threatened on 27th September, and ordered to desist from his work; since which time I have sent my little nephew for my letters and even he, on 2nd October, was stopped on the road and threatened if he continued to act as my messenger. The shopkeepers have been warned to stop all supplies to my house, and I have just received a message from the post mistress to say that the telegraph messenger was stopped and threatened on the road when bringing out a message to me and that she does not think it safe to send any telegrams which may come for me in the future for fear they should be abstracted and the messenger injured. My farm is public property; the people wander over it with impunity. My crops are trampled upon, carried away in quantities, and destroyed wholesale. The locks on my gates are smashed, the gates thrown open, the walls thrown down, and the stock driven out on the roads. I can get no workmen to do anything, and my ruin is openly avowed as the object of the Land League unless I throw up everything and leave the country. I say nothing about the danger to my own life, which is apparent to anybody who knows the country.

CHARLES C. BOYCOTT

Lough Mask House, County Mayo, 14 October

After the publication of this letter, Bernard Becker, special correspondent of the Daily News, travelled to Ireland to cover Boycott's situation.[18] On 24 October, he wrote a dispatch from Westport that contained an interview with Boycott.[18] He reported that Boycott had £500 worth of crops that would rot if help could not be found to harvest them.[18][19] According to Becker, "Personally he is protected, but no woman in Ballinrobe would dream of washing him a cravat or making him a loaf. All the people have to say is that they are sorry, but that they 'dare not.'"[19] Boycott had been advised to leave, but he told Becker that "I can hardly desert Lord Erne, and, moreover, my own property is sunk in this place."[19] Becker's report was reprinted in the Belfast News-Letter and the Dublin Daily Express.[18] On 29 October, the Dublin Daily Express published a letter proposing a fund to finance a party of men to go to County Mayo to save Boycott's crops.[18] Between them, the Daily Express, The Daily Telegraph, Daily News, and News Letter raised £2,000 to fund the relief expedition.[20]

Saving the crops

[edit]In Belfast in early November 1880, The Boycott Relief Fund was established to arrange an armed expedition to Lough Mask.[18] Plans soon gained momentum, and within days, the fund had received many subscriptions.[18] The committee had arranged with the Midland Great Western Railway for special trains to transport the expedition from Ulster to County Mayo.[18] Many nationalists viewed the expedition as an invasion.[18] The Freeman's Journal denounced the organisers of the expedition, and asked, "How is it that this Government do not consider it necessary to prosecute the promoters of these warlike expeditions?"[18][21]

William Edward Forster, Chief Secretary for Ireland, made it clear in a communication with the proprietor of the Dublin Daily Express that he would not allow an armed expedition of hundreds of men, as the committee was planning, and that 50 unarmed men would be sufficient to harvest the crops.[22] He said that the government would consider it their duty to protect this group.[22] On 10 November 1880, the relief expedition from South Ulster, consisting of one contingent from County Cavan and one from County Monaghan, left for County Mayo.[22] Additional troops had already arrived in County Mayo to protect the expedition.[22] Boycott himself said that he did not want such a large number of South Ulstermen, as he had saved the grain harvest himself, and that only ten or fifteen labourers were needed to save the root crops. He feared that bringing a large number of Ulster Protestants into County Mayo could lead to sectarian violence.[22] While local Land League leaders said that there would be no trouble from them if the aim was simply to harvest the crops, more extreme sections of the local population did threaten violence against the expedition and the troops.[22]

The expedition from South Ulster experienced hostile protests on their route through County Mayo, but there was no violence, and they harvested the crops without incident.[22] Rumours spread amongst the South Ulstermen that an attack was being planned on the farm, but none materialised.[22]

Aftermath

[edit]On 27 November 1880, Boycott, his family and a local magistrate were escorted from Lough Mask House by members of the 19th Hussars.[23] A carriage had been hired for the family, but no driver could be found for it, and an army ambulance and driver had to be used.[23] The ambulance was escorted to Claremorris railway station, where Boycott and his family boarded a train to Dublin,[23] where Boycott was received with some hostility.[23] The hotel he stayed in received letters saying that it would be 'boycotted' if Boycott remained.[23] He had intended to stay in Dublin for a week, but Boycott was advised to cut his stay short.[23] He left Dublin for England on the Holyhead mail boat on 1 December.[23]

The cost to the government of harvesting Boycott's crops was estimated at £10,000:[24] in Parnell's words, "one shilling for every turnip dug from Boycott's land".[20] In a letter requesting compensation to William Ewart Gladstone, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Boycott said that he had lost £6,000 of his investment in the estate.[25]

'Boycotting' had strengthened the power of the peasants,[26] and by the end of 1880 there were reports of boycotting from all over Ireland.[27] The events at Lough Mask had also increased the power of the Land League, and the popularity of Parnell as a leader.[27]

On 28 December 1880, Parnell and other Land League leaders were put on trial on charges of conspiracy to prevent the payment of rent.[27] The trial attracted thousands of people onto the streets outside the court. A Daily Express reporter wrote that the court reminded him "more of the stalls of the theatre on opera night".[27] On 24 January 1881, the judge dismissed the jury, it having been hung ten to two in favour of acquittal.[27] Parnell and Davitt received this news as a victory.[27]

After the boycotting, Gladstone discussed the issue of land reform, writing in an 1880 letter, "The subject of the land weighs greatly on my mind and I am working on it to the best of my ability."[28] In December 1880, the Bessborough Commission, headed by The 6th Earl of Bessborough, recommended major land reforms, including the three Fs.[29]

William Edward Forster argued that a Coercion Act—which would punish those who participated in events like those at Lough Mask, and would include the suspension of habeas corpus—should be introduced before any Land Act.[29] Gladstone eventually accepted this argument.[29] When Forster attempted to introduce the Protection of Person and Property Act 1881, Parnell and other Land League MPs attempted to obstruct its passage with tactics such as filibustering. One such filibuster lasted for 41 hours.[29] Eventually, the Speaker of the house intervened, and a measure was introduced whereby the Speaker could control the house if there was a three to one majority in favour of the business being urgent.[29] This was the first time that a check was placed on a debate in a British parliament.[29] The act was passed on 28 February 1881.[29] There was a negative reaction to the passing of the act in both England and Ireland.[29] In England, the Anti-Coercion Association was established, which was a precursor to the Labour Party.[29]

In April 1881 Gladstone introduced the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881, in which the principle of the dual ownership of the land between landlords and tenants was established, and the three Fs introduced.[30] The act set up the Irish Land Commission, a judicial body that would fix rents for a period of 15 years and guarantee fixity of tenure.[30] According to The Annual Register, the act was "probably the most important measure introduced into the House of Commons since the passing of the Reform Bill".[30]

The word boycott

[edit]According to James Redpath, the verb to boycott was coined by Father O'Malley in a discussion between them on 23 September 1880.[18] The following is Redpath's account:[18]

I said, "I'm bothered about a word."

"What is it?" asked Father John.

"Well," I said, "When the people ostracise a land-grabber we call it social excommunication, but we ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or land-agent like Boycott. Ostracism won't do – the peasantry would not know the meaning of the word – and I can't think of any other."

"No," said Father John, "ostracism wouldn't do."

He looked down, tapped his big forehead, and said: "How would it do to call it to Boycott him?"

According to Joyce Marlow, the word was first used in print by Redpath in the Inter-Ocean on 12 October 1880.[18] The coining of the word, and its first use in print, came before Boycott and his situation was widely known outside County Mayo.[18] In November 1880, an article in the Birmingham Daily Post referred to the word as a local term in connection to the boycotting of a Ballinrobe merchant.[31] Still in 1880, The Illustrated London News described how "To 'Boycott' has already become a verb active, signifying to 'ratten', to intimidate, to 'send to Coventry', and to 'taboo'".[32] In 1888, the word was included in the first volume of A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (later known as The Oxford English Dictionary).[32] According to Gary Minda in his book, Boycott in America: How Imagination and Ideology Shape the Legal Mind, "Apparently there was no other word in the English language to describe this dispute."[33] The word also entered the lexicon of languages other than English, such as Dutch, French, German, Polish and Russian.[33]

Later life

[edit]After leaving Ireland, Boycott and his family visited the United States.[34] His arrival in New York generated a great deal of media interest; the New York Tribune said that, "The arrival of Captain Boycott, who has involuntarily added a new word to the language, is an event of something like international interest."[34] The New York Times said, "For private reasons the visitor made the voyage incognito, being registered simply as 'Charles Cunningham.'"[35] The purpose of the visit was to see friends in Virginia, including Murray McGregor Blacker, a friend from his time on Achill Island who had settled in the United States.[34] Boycott returned to England after some months.[34]

In 1886, Boycott became a land agent for Hugh Adair's Flixton estate in Suffolk, England.[36] He had a passion for horses and racing, and became secretary of the Bungay race committee.[36] Boycott continued to spend holidays in Ireland, and according to Joyce Marlow, he left Ireland without bitterness.[36]

In early 1897, Boycott's health became very poor. In an attempt to improve his health, he and his wife went on a cruise to Malta.[36] In Brindisi, he became seriously ill, and had to return to England.[36] His health continued to deteriorate, and on 19 June 1897 he died at his home in Flixton, aged 65.[36] His funeral and burial took place at the church at Burgh St Peter, conducted by his nephew Arthur St John Boycott, who was at Lough Mask during the first boycott.[36] Charles Boycott's widow, Annie, was subsequently sued over the funeral expenses and other debts, and had to sell some assets.[36] A number of London newspapers, including The Times, published obituaries.[36]

In popular culture

[edit]Charles Boycott and the events that led to his name entering the English language have been the subject of several works of fiction. The first was Captain Boycott, a 1946 romantic novel by Phillip Rooney. This was the basis for the 1947 film Captain Boycott—directed by Frank Launder and starred Stewart Granger, Kathleen Ryan, Alastair Sim, and Cecil Parker as Charles Boycott.[37] More recently the story was the subject of the 2012 novel Boycott, by Colin C. Murphy.[38]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Reference to the idiom "to send to Coventry".

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Captain Charles Boycott". Keep Military Museum. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ a b Boycott, (1997) p. 4

- ^ a b c Marlow, (1973) pp. 13–14

- ^ a b c d Boycott, (1997) pp. 84–85

- ^ Marlow, (1973) p. 18

- ^ a b c d Boycott, (1997) pp. 89–95

- ^ Marlow, (1973) pp. 19–27

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Marlow, (1973) pp. 29–43

- ^ Boycott, (1997) p. 95

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Marlow, (1973) pp. 59–70

- ^ a b c Boycott, (1997) p. 212

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Marlow, (1973) pp. 133–142

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Collins, (1993) pp. 19–35

- ^ a b c d e f Collins, (1993) pp. 72–79

- ^ a b c d Collins, (1993) p. 81

- ^ Hachey et al, (1996) pp. 119

- ^ a b Boycott, (1997) p. 232

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Marlow, (1973) pp. 143–155

- ^ a b c Becker (1881) p. 1–17

- ^ a b Hickey; Doherty, (2003) p. 40

- ^ "The people of Ballinrobe and its neighbourhood..." Freeman's Journal. 5 November 1880. p. 4. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marlow, (1973) pp. 157–173

- ^ a b c d e f g Marlow, (1973) pp. 215–219

- ^ Marlow, (1973) p 224

- ^ Marlow, (1973) p. 234

- ^ Marlow, (1973) pp. 228

- ^ a b c d e f Marlow, (1973) pp. 221–231

- ^ Marlow, (1973) p. 225

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marlow, (1973) pp. 233–243

- ^ a b c Marlow, (1973) p. 249

- ^ "The Agitation in Ireland". Birmingham Daily Post. 13 November 1880. p. 5.

- ^ a b Murray, (1888) p. 1040

- ^ a b Minda, (1999) pp. 27–28

- ^ a b c d Marlow, (1973) pp. 245–249

- ^ "Arrival of Capt. Boycott" (PDF). The New York Times. 6 April 1881. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marlow, (1973) pp. 264–276

- ^ "Captain Boycott". The Irish in Film. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Bolger, Dermot (9 February 2013). "Two Brothers – and a Man Whose Name Lives on in Infamy". The Irish Independent. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Becker, Bernard H (1881). Disturbed Ireland. Macmillan and Co.

- Boycott, Charles Arthur (1997). Boycott – The Life Behind the Word. Carbonel Press. ISBN 0-9531407-0-9.

- Collins, M.E. (1993). History in the Making – Ireland 1868–1966. The Educational Company of Ireland. ISBN 0-86167-305-0.

- Hachey, Thomas E.; Hernon, Joseph M.; McCaffrey, Lawrence John (1996). The Irish Experience: A Concise History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 119. ISBN 1-56324-791-7.

parnell shun him speech.

- Hickey, D.J.; Doherty, J.E. (2003). A New Dictionary of Irish History From 1800. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-2520-3.

- Marlow, Joyce (1973). Captain Boycott and the Irish. André Deutsch. ISBN 0-233-96430-4.

- Minda, Gary (1999). Boycott in America: How Imagination and Ideology Shape the Legal Mind. Southern Illinois University. p. 227. ISBN 0-8093-2174-2.

boycott history.

- Murray, James (1888). A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Vol. 1. Clarendon Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Norgate, Gerald le Grys (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.