Milo, Maine

Milo, Maine | |

|---|---|

Bird's-eye view c. 1910 | |

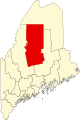

Location in Piscataquis County and the state of Maine. | |

| Coordinates: 45°15′1″N 68°58′59″W / 45.25028°N 68.98306°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maine |

| County | Piscataquis |

| Incorporated | 1823 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 33.96 sq mi (87.96 km2) |

| • Land | 32.98 sq mi (85.42 km2) |

| • Water | 0.98 sq mi (2.54 km2) |

| Elevation | 322 ft (98 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 2,251 |

| • Density | 26.4/sq mi (10.2/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 04463 |

| Area code | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-46020 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0582597 |

| Website | https://www.trcmaine.org/community/milo |

Milo is a town in Piscataquis County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,251 at the 2020 census.[2] Milo includes the village of Derby. The town sits in the valley of the Piscataquis, Sebec and Pleasant Rivers in the foothills of the Longfellow Mountains and is the gateway to many pristine hunting, fishing, hiking, boating, and other outdoor tourist locations such as Schoodic, Seboeis, and Sebec Lakes, Mount Katahdin and its backcountry in Baxter State Park and the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, Katahdin Iron Works and Gulf Hagas.

History

[edit]The community was first known as Township Number 3 in the seventh range north of the Waldo Patent. It was settled by Benjamin Sargent and his son, Theophilus, from Methuen, Massachusetts, on May 2, 1802. On January 21, 1823, it was incorporated as Milo, named after Milo of Croton, a famous athlete from ancient Croton in Magna Graecia, Italy.[3] It would become a trade center, with Trafton's Falls providing water power for early industry. In 1823, Winborn A. Swett built a dam at the 14-foot (4.3 m) river drop and erected the first sawmill. Thomas White soon added a carding and fulling mill. The Joseph Cushing & Company built a woolen textile mill in 1842, but it burned six years later.[4]

The Bangor and Piscataquis Railroad arrived in 1868–1869,[5] and Milo developed into a small mill town. It produced numerous lumber goods, and in 1879 the Boston Excelsior Company built a factory to manufacture excelsior. The American Thread Company built a factory with a narrow gauge industrial railway in 1901–1902, moving its equipment from Willimantic, Connecticut.[6]

Derby village

[edit]The early Bangor & Piscataquis and Bangor & Katahdin Iron Works railroads met at Milo Junction. After these railroads merged into the Bangor and Aroostook Railroad, Milo Junction became the company town of Derby with the second largest railroad car shop and repair facility in New England. In 1906 the railroad invested $414,448.95 in brick buildings including a two-story office, a planing mill, and an enginehouse with a 242-foot (74 m) locomotive shop and a 54,000-square-foot car shop connected by a 75-foot (23 m) transfer table moving 369 feet (112 m) back and forth above a repair pit. Employee housing initially included a 45-room hotel with a dining room for single railroad shopmen and 46 homes with bathrooms, hot water boilers, ranges, and electric lights for married men.[7] The village expanded to include stores and 72 identical employee houses arranged in four rows along First and Second Streets. These uniformly-colored structures were sold by the railroad in 1959; and the hotel became a community center.[8]

Ku Klux Klan

[edit]On Labor Day 1923, Milo became the site of the Ku Klux Klan's first daylight parade in the northern United States. Seventy-five members of the Klan marched during the town's centennial celebration.[9]

2008 fire

[edit]On September 14, 2008, a fire destroyed several buildings in downtown Milo, including a flower shop, an arcade, and a True Value hardware store. Because of the age, composition, and vicinity of these buildings, the fire easily spread and devastated much of Main Street. Fire departments from Milo and from several surrounding towns were called in to extinguish the fire. No injuries were reported. Arson was determined to be the cause.[10]

In January 2009, Christopher M. Miliano was arrested and indicted on two counts of arson, one count of theft, one count of burglary, and one count of aggravated assault; prosecutors claimed that Miliano set fire to a pub he had burglarized, resulting in the blaze.[11] In July 2009, Miliano entered a guilty plea for his offense, and was sentenced by the Piscatiquis County Superior Court to twenty years in prison, with all but eight years suspended.[12]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Sign of the Beaver is a children's historical novel by Elizabeth George Speare published in 1983. The story is set in the 18th century and follows a 12-year-old boy, Matt James Hallowell, who is building a log cabin with his father in the wilderness of Maine. Left alone at the cabin while his father leaves to retrieve the rest of the family, Matt struggles to cope with challenging survival situations and is ultimately aided by the appearance of Attean, a member of the indigenous Beaver tribe. The Sign of the Beaver was inspired by a true story dating from 1802 and documented in a history of the small town of Milo, Maine; in it, a teenage boy left to care for his family's cabin was helped by the local Natives when his supplies were ravaged by a bear. The book is one of Speare's most popular novels, winning multiple literary awards including the Scott O'Dell Award for Historical Fiction. A 1997 TV movie called Keeping the Promise was based on Speare's novel.

- The climatic charge in the Battle of Little Round Top and other events captured in Michael Shaara's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Killer Angels (1975), and Gettysburg, the 1993 movie based on the book, relied heavily on just a few surviving diaries such as the one from Milo's Sergeant William T. Livermore. His diary reads, “We were ordered to charge them when there were two to our one. With fixed bayonets and with a yell we rushed on them, which so frightened them, that not another shot was fired on us. Some threw down their arms and ran but many rose up, begging to be spared...After chasing them as far as prudent, we ‘rallied around the colors’ and gave three hearty cheers, then went back to our old position, with our prisoners.” An archive copy of his diary can be found at the Milo Historical Society.

Photo gallery

[edit]-

West Main Street c. 1905

-

Milo House in 1910

-

Milo Jct. (Derby) in 1908

-

Street sign designating Milo

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 33.96 square miles (87.96 km2), of which 32.98 square miles (85.42 km2) is land and 0.98 square miles (2.54 km2) is water.[1] The town is located at the confluence of the Sebec River and the Piscataquis River. The Pleasant River is also within the town lines, giving the town the nickname of Town of Three Rivers. Milo is located within a few miles of the exact center of the state of Maine.

Climate

[edit]This climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot summers and cold winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Milo has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.[13]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 381 | — | |

| 1840 | 756 | 98.4% | |

| 1850 | 932 | 23.3% | |

| 1860 | 959 | 2.9% | |

| 1870 | 938 | −2.2% | |

| 1880 | 934 | −0.4% | |

| 1890 | 1,029 | 10.2% | |

| 1900 | 1,150 | 11.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,556 | 122.3% | |

| 1920 | 2,894 | 13.2% | |

| 1930 | 2,912 | 0.6% | |

| 1940 | 3,000 | 3.0% | |

| 1950 | 2,898 | −3.4% | |

| 1960 | 2,756 | −4.9% | |

| 1970 | 2,572 | −6.7% | |

| 1980 | 2,624 | 2.0% | |

| 1990 | 2,600 | −0.9% | |

| 2000 | 2,383 | −8.3% | |

| 2010 | 2,340 | −1.8% | |

| 2020 | 2,251 | −3.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[15] of 2010, there were 2,340 people, 1,034 households, and 645 families residing in the town. The population density was 71.0 inhabitants per square mile (27.4/km2). There were 1,274 housing units at an average density of 38.6 per square mile (14.9/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 97.2% White, 1.0% African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.3% Asian, 0.4% from other races, and 0.8% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.9% of the population.

There were 1,034 households, of which 26.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.9% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.3% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.6% were non-families. 32.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.78.

The median age in the town was 44.7 years. 21.4% of residents were under the age of 18; 6.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 22.4% were from 25 to 44; 30% were from 45 to 64; and 19.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the town was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[16] of 2000, there were 2,383 people, 1,021 households, and 659 families residing in the town. The population density was 72.6 inhabitants per square mile (28.0/km2). There were 1,215 housing units at an average density of 37.0 per square mile (14.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.36% White, 0.34% Black or African American, 0.59% Native American, 0.21% Asian, 0.04% from other races, and 0.46% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.17% of the population.

There were 1,021 households, out of which 28.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.5% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.4% were non-families. 29.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 24.1% under the age of 18, 6.9% from 18 to 24, 26.4% from 25 to 44, 23.5% from 45 to 64, and 19.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.2 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $24,432, and the median income for a family was $31,875. Males had a median income of $27,393 versus $19,952 for females. The per capita income for the town was $12,732. About 12.8% of families and 16.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 21.7% of those under age 18 and 12.7% of those age 65 or over.

Sites of interest

[edit]- Milo Historical Society & Museum

- Harrigan Learning Center and Museum

- Milo-Brownville & Points North Visitors Center

- Milo Public Library

- Veterans Park

- Doble Park

- Maine ITS Snowmobile Trails – ITS 82 and 83

- ATV trails

Education

[edit]- Penquis Valley High School

- Penquis Valley Middle School

- Milo Elementary

- Brownville Elementary

Notable people

[edit]- Wilder Stevens Metcalf, U.S. Army major general, member of the Kansas Senate

- Oswald Tippo, Botanist and educator

- Edward Youngblood, State legislator

References

[edit]- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Milo town, Piscataquis County, Maine". Retrieved January 17, 2022.

- ^ Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts: A.J. Coolidge. p. 210.

coolidge mansfield history description new england 1859.

- ^ Varney, George J. (1886), Gazetteer of the state of Maine. Milo, Boston: Russell

- ^ Angier, Jerry & Cleaves, Herb (1986). Bangor and Aroostook: The Maine Railroad. Flying Yankee Enterprises. p. 1. ISBN 0-9615574-2-7.

- ^ Angier, Jerry (2004). Bangor and Aroostook RR in Color. Morning Sun Books. p. 51. ISBN 1-58248-134-2.

- ^ Strout, W. Jerome (1966). 75 Years The Bangor and Aroostook. Bangor, Maine: Bangor and Aroostook Railroad. pp. 29&30.

- ^ Melvin, George F. (2010). Bangor and Aroostook in Color, Volume Two. Morning Sun Books. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-58248-285-9.

- ^ Moore, Joshua (2008). What's in a Picture. Downeast. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-89272-778-0.

- ^ Fire devastates downtown Milo, Bangor Daily News, September 15, 2008

- ^ Milo man indicted on arson charges Archived July 11, 2012, at archive.today, Bangor Daily News, January 29, 2009

- ^ Man Sentenced For Arson In Milo, WCSH-TV, July 14, 2009

- ^ Climate Summary for Milo, Maine

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.