The Cocoanuts

| The Cocoanuts | |

|---|---|

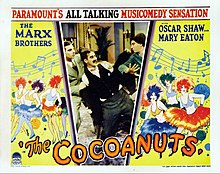

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Florey Joseph Santley |

| Written by | George S. Kaufman (play) Morrie Ryskind |

| Produced by | Monta Bell Walter Wanger (uncr.) |

| Starring | Groucho Marx Harpo Marx Chico Marx Zeppo Marx |

| Cinematography | George J. Folsey J. Roy Hunt |

| Edited by | Barney Rogan (uncr.) |

| Music by | Irving Berlin Victor Herbert (uncr.) Frank Tours (uncr.) Georges Bizet (uncr.)[citation needed] |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $500,000 (estimated) |

| Box office | $1.8 million (worldwide rentals)[1] |

The Cocoanuts is a 1929 pre-Code musical comedy film starring the Marx Brothers (Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Zeppo). Produced for Paramount Pictures by Walter Wanger, who is not credited, the film also stars Mary Eaton, Oscar Shaw, Margaret Dumont and Kay Francis. The first sound film to credit more than one director (Robert Florey and Joseph Santley), it was adapted to the screen by Morrie Ryskind from the George S. Kaufman Broadway musical play. Five of the film's tunes were composed by Irving Berlin, including "When My Dreams Come True", sung by Oscar Shaw and Mary Eaton.

Plot

[edit]The Cocoanuts is set in the Hotel de Cocoanut, a resort hotel, during the Florida land boom of the 1920s. Mr. Hammer runs the hotel, assisted by Jamison. Harpo and Chico arrive with empty luggage, which they apparently plan to fill by robbing and conning the guests. Wealthy Mrs. Potter is one of the few paying customers. Her daughter Polly is in love with struggling young architect Bob Adams. He works to support himself as a clerk at the hotel, but has grand plans for the development of the entire area as Cocoanut Manor. Mrs. Potter wants her daughter to marry Harvey Yates, whom she believes to be of higher social standing than Adams. Yates is actually a confidence man out to steal the dowager's expensive diamond necklace with the help of his partner in crime, Penelope.

Analysis

[edit]The somewhat thin plot primarily provides a framework for the running gags of the Marx Brothers to take prominence. The film is, however, notable for its musical production numbers, including cinematic techniques which were soon to become standard, such as overhead shots of dancing girls imitating the patterns of a kaleidoscope. The musical numbers were not pre-recorded, but were shot live on the soundstage with an off-camera orchestra. The main titles are superimposed over a negative image of the "Monkey-Doodle-Do" number photographed from an angle that does not appear in the body of the film.

One of the more famous gag routines in the film involves Chico not knowing what a "viaduct" is, which Groucho keeps mentioning, prompting Chico to ask, "why-a-duck".

In another sequence, while he is acting as auctioneer for some land of possibly questionable value ("You can have any kind of a home you want to; you can even get stucco! Oh, how you can get stuck-oh!"), Groucho has hired Chico to act as a shill to inflate the sale prices by making bogus bids. To Groucho's frustration, Chico keeps outbidding everyone, even himself. During the auction, Mrs. Potter announces that her necklace has been stolen and offers a reward of one thousand dollars, whereupon Chico offers two thousand. Unbeknownst to anyone except the thieves and to Harpo (who intercepted the map drawn by the villains while hiding under their hotel room bed) the jewellery's hiding place is a hollow tree stump adjacent to where the land auction takes place.

Thereupon, Detective Hennessy who entered the plot earlier, decides that the guilty party is Polly's suitor. He is aided by the real villains, who attempt to frame Bob Adams for the crime. However, Harpo, by producing the necklace, and later the note, is able to prove that Bob Adams is innocent of the charges laid against him.

At various points, Harpo and Chico both provide musical solos – Harpo on the harp, and Chico at the piano.

Still another sequence has Groucho, Mrs. Potter and Harvey Yates (the necklace thief) make formal speeches. Harpo repeatedly walks off, with a grimace on his face, to the punch bowl. (His staggering implies that the punch has been spiked with alcohol.) Another highlight is when the cast, already dressed in traditional Spanish garb for a theme party, erupts into an operatic treatment about Hennessy's lost shirt to music from Bizet's Carmen (specifically, Habanera and the Toreador Song). An earlier scene shows Harpo and Chico abusing a cash register while whistling the Anvil Chorus from Il trovatore, a piece also referenced in several other Marx Brothers films.

Immediately following the revelation that an injustice has been done to Polly's original suitor, Bob Adams, Mr. Adams himself comes in saying there's a man outside asking for Mr. Hammer: it is tycoon John W. Berryman, who is about to buy Bob's architectural designs for Cocoanut Manor, and asking if the hotel can accommodate 400 guests for the weekend. The Marxes immediately beat a hasty retreat, and Mrs. Potter declares the wedding will take place "exactly as planned, with the exception of a slight change," announcing that Mr. Robert Adams will be the bridegroom.

Cast

[edit]

- Groucho Marx as Mr. Hammer

- Harpo Marx as Harpo

- Chico Marx as Chico

- Zeppo Marx as Jamison

- Mary Eaton as Polly Potter

- Oscar Shaw as Bob Adams

- Margaret Dumont as Mrs. Potter

- Kay Francis as Penelope

- Cyril Ring as Harvey Yates

- Basil Ruysdael as Detective Hennessy

Dancers:

- Gamby-Hale Girls

- Allan K. Foster Girls

Production

[edit]Principal photography began on Monday, 4 February 1929, at Paramount’s Astoria studio. The Marx Brothers shot their contributions during the day. At night, they traveled to the 44th Street Theatre, where they were concurrently performing the 1928 Broadway musical Animal Crackers.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Referring to directors Robert Florey and Joseph Santley, Groucho Marx remarked, "One of them didn't understand English and the other didn't understand Harpo."[13]

As was common in the early days of sound film, to eliminate the sound of the camera motors, the cameras and the cameramen were enclosed in large soundproof booths with glass fronts to allow filming. This resulted in largely static camera work. For many years, Marxian legend had it that Florey, who had never seen the Marxes' work before, was put in the soundproof booth because he could not contain his laughter at the brothers' spontaneous antics.[14]

Every piece of paper in the movie is soaking wet, in order to keep crackling paper sounds from overloading the primitive recording equipment of the time. Director Florey struggled with the noises until the 27th take of the "Viaduct" scene. He finally got the idea to soak the paper in water; the 28th take of the "Viaduct" scene used soaked paper, and this take was quiet and used in the film.[15]

The "ink" that Harpo drank from the hotel lobby inkwell was actually Coca-Cola, and the "telephone mouthpiece" that he nibbled was made of chocolate, both inventions of Robert Florey.

Paramount brought conductor Frank Tours (1877–1963) over from London to be the film's musical director, as he had also been the conductor for the show's original Broadway production in 1925. At the time, Tours had been conducting at the Plaza Theatre in Piccadilly Circus (Paramount's premier exhibition venue in the UK). Filming took place at the Paramount studios in Astoria, Queens; their second film, Animal Crackers, was also shot there. After that, production of all Marx films moved to Hollywood.

Songs

[edit]- "Florida by the Sea" (instrumental with brief vocal by chorus during opening montage)

- "When My Dreams Come True" (theme song, Mary Eaton and Oscar Shaw variously, several reprises)

- "The Bell-Hops" (instrumental, dance number)

- "Monkey Doodle Doo" (vocal by Mary Eaton and dance number)

- "Ballet Music" (instrumental, dance number)

- "Tale of the Shirt" (vocal by Basil Ruysdael, words set to music from Carmen by Georges Bizet)

- "Tango Melody" (vocal included in the stage production, used in the film as background music only)

- "Gypsy Love Song" (by Victor Herbert, piano solo by Chico Marx)

Several songs from the stage play were omitted from the film: "Lucky Boy", sung by the chorus to congratulate Bob on his engagement to Polly and "A Little Bungalow", a love duet sung by Bob and Polly that was replaced with "When My Dreams Come True" in the film.

Irving Berlin wrote two songs entitled "Monkey Doodle Doo". The first was published in 1913, the second introduced in the 1925 stage production and featured in the film. They are very different songs.

Although legend claims Berlin wrote the song "Always" for The Cocoanuts, he never meant for the song to be included, writing it, instead, as a gift for his fiancée.[16]

Reception

[edit]When the Marx Brothers were shown the final cut of the film, they were so horrified they tried to buy the negative back and prevent its release.[17] Paramount wisely resisted — the movie turned out to be a big box office hit, with a $1,800,000 gross making it one of the most successful early talking films.[1]

It received mostly positive reviews from critics, with the Marx Brothers themselves earning most of the praise while other aspects of the film drew a more mixed reaction. Mordaunt Hall of The New York Times reported that the film "aroused considerable merriment" among the viewing audience, and that a sequence using an overhead shot was "so engaging that it elicited plaudits from many in the jammed theatre." However, he found the audio quality during some of the singing to be "none too good", adding, "a deep-voiced bass's tones almost fade into a whisper in a close-up. Mary Eaton is charming, but one obtains little impression of her real ability as a singer."[18]

Variety called it "a comedy hit for the regular picture houses. That's all it has – comedy – but that's enough." It reported the sound had "a bit of muffling now and then" and that the dancers weren't always filmed well: "When the full 48 were at work only 40 could be seen and those behind the first line could be seen but dimly."[19]

"It is as a funny picture and not as a musical comedy, not for its songs, pretty girls, or spectacular scenes, that The Cocoanuts succeeds", wrote John Mosher in The New Yorker. "Neither Mary Eaton, nor Oscar Shaw, who contribute the "love interest", is effective, nor are the chorus scenes in the least superior to others of the same sort in various musical-comedy-movies now running in town. To the Marxes belongs the success of the show, and their peculiar talents seem, surprisingly enough, even more manifest on the screen than on the stage."[20]

Film Daily called it "a good amount of fun, although some of it proves tiresome. This is another case of a musical comedy transferred almost bodily to the screen and motion picture treatment forgotten. The result is a good many inconsistencies which perhaps may be overlooked provided the audience accepts the offering for what it is."[21]

Accolades

[edit]- American Film Institute – recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs – nominated

See also

[edit]- Animal Crackers (1930), the next Marx Brothers film

- List of American films of 1929

- List of early sound feature films (1926–1929)

- List of United States comedy films

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Big Sound Grosses". Variety. New York. June 21, 1932. p. 62.

- ^ "The Cocoanuts (1929)". American Film Institute Catalog. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Bader, Robert S. (2016). "The Marx Brothers: From Vaudeville to Hollywood". MarxBrothers.net. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Marx Cocoanuts 1929". alamy. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Marx Cocoanuts 1929". Getty Images. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Brennan, John V.; Larrabee, John (2010). "The Cocoanuts". The Age of Comedy. Laurel and Hardy Central. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Antos, Jason D. (August 30, 2021). "When Astoria Was America's Hollywood". Give Me Astoria. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Marx Brothers". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "A Visit to Astoria, Then & Now: The Marx Brothers at Paramount Pictures and Notes on Contemporary Attractions". Walking Off the Big Apple. July 2, 2009. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Koking, Natalie (December 12, 2017). "Hollywood: The Films that Made the Marx Brothers Legends". Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Siler, Bob Siler. "Places where the Marx Brothers lived". Marx-Brothers.org. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Backes, Aaron D. (September 10, 2021). "History of Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, New York". ClassicNewYorkHistory.com. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ Bowen, Peter (August 3, 2010). "The Cocoanuts Released". Focus Features. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Paul D. Zimmerman, The Marx Brothers At The Movies. Putnam, 1968, p. 17.

- ^ Paul D. Zimmerman and Burt Goldblatt The Marx Brothers at the Movies. Putnam, 1968, p.26.

- ^ Bader, Robert S. (2016). Four of the Three Musketeers: The Marx Brothers on Stage. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. p. 309. ISBN 9780810134164.

- ^ Nixon, Rob. "The Cocoanuts". TCM.com. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (May 25, 1929). "Movie Review – The Cocoanuts". The New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ^ "The Cocoanuts". Variety. New York: 14. May 29, 1929.

- ^ Mosher, John (June 1, 1929). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 74.

- ^ "The Cocoanuts". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc. June 2, 1929. p. 9.

External links

[edit]- The Cocoanuts at IMDb

- The Cocoanuts at the TCM Movie Database

- The Cocoanuts at AllMovie

- The Cocoanuts at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Cocoanuts - The Marx Brothers Council Podcast

- Robert Wilfred Franson 2004 The Cocoanuts (1929) Film Review

- 1929 films

- 1929 musical comedy films

- American musical comedy films

- 1920s English-language films

- American black-and-white films

- Marx Brothers (film series)

- Films set in Florida

- Films set in hotels

- Paramount Pictures films

- Films directed by Robert Florey

- Films directed by Joseph Santley

- Films produced by Walter Wanger

- Films scored by Irving Berlin

- Films shot at Astoria Studios

- Films based on musicals

- 1920s American films

- English-language musical comedy films