William Carey (missionary)

William Carey | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Carey, c. 1887 | |

| Born | 17 August 1761 Paulerspury, England |

| Died | 9 June 1834 (aged 72) Serampore, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Signature | |

| |

William Carey (17 August 1761 – 9 June 1834) was an English Christian missionary, Particular Baptist minister, translator, social reformer and cultural anthropologist who founded the Serampore College and the Serampore University, the first degree-awarding university in India[1] and cofounded the Serampore Mission Press.

He went to Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1793, but was forced to leave the British Indian territory by non-Baptist Christian missionaries.[2] He joined the Baptist missionaries in the Danish colony of Frederiksnagore in Serampore. One of his first contributions was to start schools for impoverished children where they were taught reading, writing, accounting and Christianity.[3] He opened the first theological university in Serampore offering divinity degrees,[4][5] and campaigned to end the practice of sati.[6]

Carey is known as the "father of modern missions."[7] His essay, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens, led to the founding of the Baptist Missionary Society.[2][8] The Asiatic Society commended Carey for "his eminent services in opening the stores of Indian literature to the knowledge of Europe and for his extensive acquaintance with the science, the natural history and botany of this country and his useful contributions, in every branch."[9]

He translated the Hindu classic, the Ramayana, into English,[10] and the Bible into Bengali, Punjabi,[11] Oriya, Assamese, Marathi, Hindi and Sanskrit.[2] William Carey has been called a reformer and illustrious Christian missionary.[1][12][13]

Early life

[edit]

William Carey, the oldest of five children, was born to Edmund and Elizabeth Carey, who were weavers by trade, in the hamlet of Pury End in the parish of Paulerspury, Northamptonshire.[14][15] William was raised in the Church of England; when he was six, his father was appointed the parish clerk and village schoolmaster. As a child he was inquisitive and keenly interested in the natural sciences, particularly botany. He possessed a natural gift for language, teaching himself Latin.

At the age of 14, Carey's father apprenticed him to a cordwainer in the nearby village of Piddington, Northamptonshire.[16] His master, Clarke Nichols, was a churchman like himself, but another apprentice, John Warr, was a Dissenter. Through his influence Carey would leave the Church of England and join with other Dissenters to form a small Congregational church in nearby Hackleton. While apprenticed to Nichols, he also taught himself Greek with the help of Thomas Jones, a local weaver who had received a classical education.

When Nichols died in 1779, Carey went to work for the local shoemaker, Thomas Old; he married Old's sister-in-law Dorothy Plackett in 1781 in the Church of St John the Baptist, Piddington. Unlike William, Dorothy was illiterate; her signature in the marriage register is a crude cross. William and Dorothy Carey had seven children, five sons and two daughters; both girls died in infancy, as did son Peter, who died at the age of 5. Thomas Old himself died soon afterward, and Carey took over his business, during which time he taught himself Hebrew, Italian, Dutch, and French, often reading while working on the shoes.[citation needed]

Carey acknowledged his humble origins and referred to himself as a cobbler. John Brown Myers titled his biography of Carey William Carey the Shoemaker Who Became the Father and Founder of Modern Missions.

Founding of the Baptist Missionary Society

[edit]

Carey became involved with a local association of Particular Baptists that had recently formed, where he became acquainted with men such as John Ryland, John Sutcliff, and Andrew Fuller, who would become his close friends in later years. They invited him to preach in their church in the nearby village of Earls Barton every other Sunday. On 5 October 1783, William Carey was baptised by Ryland and committed himself to the Baptist denomination.

In 1785, Carey was appointed the schoolmaster for the village of Moulton. He was also invited to serve as pastor to the local Baptist church. During this time he read Jonathan Edwards' Account of the Life of the Late Rev. David Brainerd and the journals of the explorer James Cook, and became concerned with propagating the Christian Gospel throughout the world. John Eliot (c. 1604 – 21 May 1690), Puritan missionary in New England, and David Brainerd (1718–47) became the "canonized heroes" and "enkindlers" of Carey.[17]

In 1789 Carey, became the full-time pastor of Harvey Lane Baptist Church in Leicester. Three years later, in 1792, he published his groundbreaking missionary manifesto, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. This short book consists of five parts. The first part is a theological justification for missionary activity, arguing that the command of Jesus to make disciples of all the world (Matthew 28:18-20) remains binding on Christians.[18]

The second part outlines a history of missionary activity, beginning with the early Church and ending with David Brainerd and John Wesley.[18]

Part 3 comprises 26 pages of tables, listing area, population, and religion statistics for every country in the world. Carey had compiled these figures during his years as a schoolteacher. The fourth part answers objections to sending missionaries, such as difficulty learning the language or danger to life. Finally, the fifth part calls for the formation by the Baptist denomination of a missionary society and describes the practical means by which it could be supported. Carey's seminal pamphlet outlines his basis for missions: Christian obligation, wise use of available resources, and accurate information.[citation needed]

Carey later preached a pro-missionary sermon (the Deathless Sermon), using Isaiah 54:2–3 as his text, in which he repeatedly used the epigram which has become his most famous quotation:

Expect great things from God; attempt great things for God.

Carey finally overcame the resistance to missionary effort, and the Particular Baptist Society for the Propagation of the Gospel Amongst the Heathen (subsequently the Baptist Missionary Society and since 2000 BMS World Mission) was founded in October 1792, including Carey, Andrew Fuller, John Ryland, and John Sutcliff as charter members. They then concerned themselves with practical matters such as raising funds, as well as deciding where they would direct their efforts. A medical missionary, Dr John Thomas, had been in Calcutta and was in England raising funds; they agreed to support him and that Carey would accompany him to India.

Missionary life in India

[edit]

Carey, his eldest son Felix, Thomas and his wife and daughter sailed from London aboard a British ship in April 1793. Dorothy Carey had refused to leave England, being pregnant with their fourth son and having never been more than a few miles from home; but before they left they asked her again to come with them and she gave consent, with the knowledge that her sister Kitty would help her give birth. En route they were delayed at the Isle of Wight, at which time the captain of the ship received word that he endangered his command if he conveyed the missionaries to Calcutta, as their unauthorised journey violated the trade monopoly of the British East India Company. He decided to sail without them, and they were delayed until June when Thomas found a Danish captain willing to offer them passage. In the meantime, Carey's wife, who had by now given birth, agreed to accompany him provided her sister came as well. They landed at Calcutta in November.[19]

During the first year in Calcutta, the missionaries sought means to support themselves and a place to establish their mission. They also began to learn the Bengali language to communicate with others. A friend of Thomas owned two indigo factories and needed managers, so Carey moved with his family west to Midnapore. During the six years that Carey managed the indigo plant, he completed the first revision of his Bengali New Testament and began formulating the principles upon which his missionary community would be formed, including communal living, financial self-reliance, and the training of indigenous ministers. His son Peter died of dysentery, which, along with other causes of stress, resulted in Dorothy suffering a nervous breakdown from which she never recovered.[19]

Meanwhile, the missionary society had begun sending more missionaries to India. The first to arrive was John Fountain, who arrived in Midnapore and began teaching. He was followed by William Ward, a printer; Joshua Marshman, a schoolteacher; David Brunsdon, one of Marshman's students; and William Grant, who died three weeks after his arrival. Because the East India Company was still hostile to missionaries, they settled in the Danish colony in Serampore and were joined there by Carey on 10 January 1800.[19]

Late Indian period

[edit]

Once settled in Serampore, the mission bought a house large enough to accommodate all of their families and a school, which was to be their principal means of support. Ward set up a print shop with a secondhand press Carey had acquired and began the task of printing the Bible in Bengali. In August 1800 Fountain died of dysentery.[20] By the end of that year, the mission had their first convert, a Hindu named Krishna Pal. They had also earned the goodwill of the local Danish government and Richard Wellesley, then Governor-General of India.

In May 1799 William Ward and Hannah and Joshua Marshman arrived from England and joined Carey in his work.[21] The three men became known as the Serampore trio.[22]

The conversion of Hindus to Christianity posed a new question for the missionaries concerning whether it was appropriate for converts to retain their caste. In 1802, the daughter of Krishna Pal, a Sudra, married a Brahmin. This wedding was a public demonstration that the church repudiated the caste distinctions.

Brunsdon and Thomas died in 1801. The same year, the Governor-General founded Fort William College, a college intended to educate civil servants. He offered Carey the position of professor of Bengali. Carey's colleagues at the college included pundits, whom he could consult to correct his Bengali testament. One of his colleagues was Madan Mohan who taught him the Sanskrit language.[23][citation needed] He also wrote grammars of Bengali and Sanskrit, and began a translation of the Bible into Sanskrit. He also used his influence with the Governor-General to help put a stop to the practices of infant sacrifice and suttee, after consulting with the pundits and determining that they had no basis in the Hindu sacred writings (although the latter would not be abolished until 1829).

Dorothy Carey died in 1807.[24] Due to her debilitating mental breakdown, she had long since ceased to be an able member of the mission, and her condition was an additional burden to it. John Marshman wrote how Carey worked away on his studies and translations, "…while an insane wife, frequently wrought up to a state of most distressing excitement, was in the next room…".

Several friends and colleagues had urged William to commit Dorothy to an asylum. But he recoiled at the thought of the treatment she might receive in such a place and took the responsibility to keep her within the family home, even though the children were exposed to her rages.[25]

In 1808 Carey remarried. His new wife Charlotte Rhumohr, a Danish member of his church was, unlike Dorothy, Carey's intellectual equal. They were married for 13 years until her death.

From the printing press at the mission came translations of the Bible in Bengali, Sanskrit, and other major languages and dialects. Many of these languages had never been printed before; William Ward had to create punches for the type by hand. Carey had begun translating literature and sacred writings from the original Sanskrit into English to make them accessible to his own countryman. On 11 March 1812, a fire in the print shop caused £10,000 in damages and lost work. Among the losses were many irreplaceable manuscripts, including much of Carey's translation of Sanskrit literature and a polyglot dictionary of Sanskrit and related languages, which would have been a seminal philological work had it been completed. However, the press itself and the punches were saved, and the mission was able to continue printing in six months. In Carey's lifetime, the mission printed and distributed the Bible in whole or part in 44 languages and dialects.

Also, in 1812, Adoniram Judson, an American Congregational missionary en route to India, studied the scriptures on baptism in preparation for a meeting with Carey. His studies led him to become a Baptist. Carey's urging of American Baptists to take over support for Judson's mission, led to the foundation in 1814 of the first American Baptist Mission board, the General Missionary Convention of the Baptist Denomination in the United States of America for Foreign Missions, later commonly known as the Triennial Convention. Most American Baptist denominations of today are directly or indirectly descended from this convention.

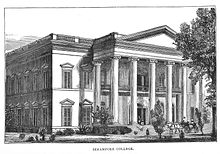

In 1818, the mission founded Serampore College to train indigenous ministers for the growing church and to provide education in the arts and sciences to anyone regardless of caste or country. Frederick VI, King of Denmark, granted a royal charter in 1827 that made the college a degree-granting institution, the first in Asia.[26]

In 1820 Carey founded the Agri Horticultural Society of India at Alipore, Calcutta, supporting his enthusiasm for botany. When William Roxburgh went on leave, Carey was entrusted to maintain the Botanical Garden at Calcutta. The genus Careya was named after him.[27]

Carey's second wife, Charlotte, died in 1821, followed by his eldest son Felix. In 1823 he married a third time, to a widow named Grace Hughes.

Internal dissent and resentment was growing within the Missionary Society as its numbers grew, the older missionaries died, and they were replaced by less experienced men. Some new missionaries arrived who were not willing to live in the communal fashion that had developed, one going so far as to demand "a separate house, stable and servants." Unused to the rigorous work ethic of Carey, Ward, and Marshman, the new missionaries thought their seniors - particularly Marshman - to be dictatorial, assigning them work not to their liking.

Andrew Fuller, who had been secretary of the Society in England, had died in 1815, and his successor, John Dyer, was a bureaucrat who attempted to reorganise the Society along business lines and manage every detail of the Serampore mission from England. Their differences proved to be irreconcilable, and Carey formally severed ties with the missionary society he had founded, leaving the mission property and moving onto the college grounds. He lived a quiet life until his death in 1834, revising his Bengali Bible, preaching, and teaching students. The couch on which he died, on 9 June 1834, is now housed at Regent's Park College, the Baptist hall of the University of Oxford.

Life in India

[edit]Much of what is known about Carey's activities in India is from missionary reports sent back home. Historians such as Comaroffs, Thorne, Van der Veer and Brian Pennington note that the representation of India in these reports must be examined in their context and with care for its evangelical and colonial ideology.[12] The reports by Carey were conditioned by his background, personal factors and his own religious beliefs. The polemic notes and observations of Carey, and his colleague William Ward, were in a community suffering from extreme poverty and epidemics, and they constructed a view of the culture of India and Hinduism in light of their missionary goals.[12][29] These reports were by those who had declared their conviction in foreign missionary work, and the letters describe experiences of foreigners who were resented by both the Indian populace as well as European officials and competing Christian groups. Their accounts of culture and Hinduism were forged in Bengal that was physically, politically and spiritually difficult to preach in.[12] Pennington summarises the accounts reported by Carey and his colleagues as follows,

Plagued with anxieties and fears about their own health, regularly reminded of colleagues who had lost their lives or reason, uncertain of their own social location, and preaching to crowds whose reactions ranged from indifference to amusement to hostility, missionaries found expression for their darker misgivings in their production of what is surely part of their speckled legacy: a fabricated Hinduism crazed by blood-lust and devoted to the service of devils.[12]

Carey recommended that his fellow Anglo-Indians learn and interpret Sanskrit in a manner "compatible with colonial aims",[30] writing that "to gain the ear of those who are thus deceived, it is necessary for them to believe that the speaker has a superior knowledge of the subject. In these circumstances, knowledge of Sanskrit is valuable."[30] According to Indian historian V. Rao, Carey lacked tolerance, understanding and respect for Indian culture, with him describing Indian music as "disgusting" and bringing to mind practices "dishonorable" to God. Such attitudes affected the literature authored by Carey and his colleagues.[13]

Family history

[edit]Biographies of Carey, such as those by F. D. Walker[31] and J. B. Myers, only allude to Carey's distress caused by the mental illness and subsequent breakdown suffered by his wife, Dorothy, in the early years of their ministry in India. More recently, Beck's biography of Dorothy Carey paints a more detailed picture: William Carey uprooted his family from all that was familiar and sought to settle them in one of the most unlikely and difficult cultures in the world for an uneducated 18th-century British working-class woman. Faced with enormous difficulties in adjusting to all this change, she failed to make the adjustment emotionally and ultimately, mentally, and her husband seemed unable to help her.[32] Carey even wrote to his sisters in England on 5 October 1795, "I have been for some time past in danger of losing my life. Jealousy is the great evil that haunts her mind."[33]

Dorothy's mental breakdown ("at the same time William Carey was baptizing his first Indian convert and his son Felix, his wife was forcefully confined to her room, raving with madness"[34]) led inevitably to other family problems. Joshua Marshman was appalled by Carey's neglect of his four boys when he first met them in 1800. Aged 4, 7, 12 and 15, they were unmannered, undisciplined, and uneducated.[35]

Eschatology

[edit]Besides Iain Murray's study, The Puritan Hope,[36] less attention has been paid in Carey's numerous biographies to his postmillennial eschatology as expressed in his major missionary manifesto, notably not even in Bruce J. Nichols's article "The Theology of William Carey."[37] Carey was a Calvinist."[38] and a postmillennialist. Even the two dissertations that discuss his achievements (by Oussoren[39] and Potts[40]) ignore large areas of his theology. Neither mentions his eschatological views, which played a major role in his missionary zeal.[41] One exception, in James Beck's biography of his first wife,[32] mentions his personal optimism in the chapter on "Attitudes Towards the Future," but not his optimistic perspective on world missions, which derived from postmillennial theology.[42]

Translation, education, and schools

[edit]

Carey devoted great efforts and time to the study not only of the common language of Bengali, but to many other Indian vernaculars, and the ancient root language of Sanskrit. In collaboration with the College of Fort William, Carey undertook the translation of the Hindu classics into English, beginning with the Ramayana. He then translated the Bible into Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, and Sanskrit, and parts of it into other dialects and languages.[43] For 30 years Carey served in the college as the professor of Bengali, Sanskrit and Marathi,[43][44] publishing, in 1805, the first book on Marathi grammar.[45][46]

The Serampore Mission Press that Carey founded is credited as the only press that "consistently thought it important enough that costly fonts of type be cast for the irregular and neglected languages of the Indian people.".[47] Carey and his team produced textbooks, dictionaries, classical literature, and other publications that served primary school children, college-level students, and the general public, including the first systematic Sanskrit grammar, which served a model for later publications.[48]

In the latter 1700s and early 1800s in India, only children of certain social strata received education, and even that was limited to basic accounting and Hindu religion. Only the Brahmins and writer castes could read, and only men, women being completely unschooled. Carey started Sunday Schools in which children learned to read using the Bible as their textbook.[49] In 1794, he opened, at his own cost, what is considered the first primary school in India.[50] The public school system that Carey initiated expanded to include girls in an era when the education of the female was considered unthinkable. Carey's work is considered to have started what became the Christian Vernacular Education Society, providing English medium education across India.[51]

Legacy

[edit]Carey spent 41 years in India without a furlough. His mission included about 700 converts in a nation of millions, but he had laid an impressive foundation of Bible translations, education, and social reform.[52] He has been called the "father of modern missions"[7] and "India's first cultural anthropologist."[53]

His teaching, translations, writings and publications, his educational establishments and influence in social reform are said to have "marked the turning point of Indian culture from a downward to an upward trend".

[Carey] saw India not as a foreign country to be exploited, but as his heavenly Father's land to be loved and saved... he believed in understanding and controlling nature instead of fearing, appeasing or worshipping it; in developing one's intellect instead of killing it as mysticism taught. He emphasized enjoying literature and culture instead of shunning it as maya.

Carey was instrumental in launching Serampore College in Serampore.[55]

Carey's passionate insistence on change resulted in the founding of the Baptist Missionary Society.[56]

Many schools are named after him:

- William Carey Christian School (WCCS) in Sydney, NSW

- William Carey International University, founded in 1876 in Pasadena, California

- Carey Theological College in Vancouver, British Columbia

- Carey Baptist College in Auckland, New Zealand

- Carey Baptist Grammar School in Melbourne, Victoria

- Carey College in Colombo, Sri Lanka

- William Carey University, founded in Hattiesburg, Mississippi in 1892,[57]

- Carey Baptist College in Perth, Australia

- Carey Mission and school in the western frontier of Michigan: Founded by Baptist missionary to the tribes Isaac McCoy in 1822

- The William Carey Academy of Chittagong, Bangladesh has kindergarten to grade 12.

- The William Carey Memorial School: A co-ed English medium in Serampore, Hooghly.

- William Carey International School: An English-medium school established on 17 August 2008 in Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Artefacts

[edit]St James Church in Paulerspury, Northamptonshire, where Carey was christened and attended as a boy, has a William Carey display. Carey Baptist Church in Moulton, Northamptonshire, also has a display of artefacts related to William Carey, as well as the nearby cottage where he lived.[60]

In Leicester, Harvey Lane Baptist Church, the last church in England where Carey served before he left for India, was destroyed by a fire in 1921. Carey's nearby cottage had served as a Memories of Carey museum from 1915 until it was destroyed to make way for a new road system in 1968.[61] Artefacts from the museum were given to Central Baptist Church in Charles Street, Leicester which houses the William Carey Museum.[62][63]

Angus Library and Archive in Oxford holds the largest single collection of Carey letters as well as numerous artefacts such as his Bible and the sign from his cordwainer shop. There is a large collection of historical artefacts including letters, books, and other artefacts that belonged to Carey at the Center for Study of the Life and Work of William Carey at Donnell Hall on the William Carey University Hattiesburg campus.[64]

See also

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Baptists |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity in India |

|---|

|

- Carey Baptist Church in Reading, England

- Carey Saheber Munshi

- William Carey University, Meghalaya

- Baptist Missionary Society

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mangalwadi, Vishal (1999). The Legacy of William Carey: A Model for the Transformation of a Culture. Crossway Books. pp. 61–67. ISBN 978-1-58134-112-6.

- ^ a b c William Carey British missionary Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Riddick, John F. (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Praeger Publications. p. 158. ISBN 0-313-32280-5.

- ^ "Northants celebrates 250th anniversary of William Carey". BBC News. 18 August 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Smith, George (1922). The Life of William Carey: Shoemaker & Missionary. J. M. Dent & Co. p. 292.

- ^ Sharma, Arvind (1988). Sati: Historical and Phenomenological Essays. Motilal Benarasidass. pp. 57–63. ISBN 81-208-0464-3.

- ^ a b Gonzalez, Justo L. (2010) The Story of Christianity Vol. 2: The Reformation to the Present Day, Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-06185589-4, p. 419

- ^ William Carey, An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens (1792; repr., London: Carey Kingsgate Press, 1961)

- ^ Thomas, T. Jacob (1994). "Interaction of the Gospel and Culture in Bengal" (PDF). Indian Journal of Theology. 36 (2). Serampore College Theology Department and Bishop's College, Kolkata: 46, 47.

- ^ Kopf, David (1969). British Orientalism and the Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1778–1835. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. pp. 70, 78.

- ^ "Saving souls and promoting good grammar". 7 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Brian K. Pennington (2005), Was Hinduism Invented?: Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction, pp. 76–77, Oxford University Press

- ^ a b V Rao (2007), Contemporary Education, pp. 17–18, ISBN 978-81-3130273-6

- ^ "Paulerspury: Pury End". The Carey Experience. Retrieved 9 July 2016.

- ^ "William Carey's Historical Wall – Carey Road, Pury End, Northamptonshire, UK". UK Historical Markers. Waymarking.com. Retrieved 9 July 2016. Includes image of memorial stone

- ^ "Glimpses #45: William Carey's Amazing Mission". Christian History Institute. Archived from the original on 4 April 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Carpenter, John, (2002) "New England Puritans: The Grandparents of Modern Protestant Missions," Fides et Historia 30.4, 529.

- ^ a b An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians, to use means for the Conversion of the Heathens reprinted London: Carey Kingsgate Press, 1961

- ^ a b c "Note from the preparer of this etext_ I have had to insert a view comments mainly in regards to adjustments to fonts to allow".

- ^ Woodall, R. (12 September 1946). "Fountain" (PDF). wmcarey.edu. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ William Carey University website, William Ward, Chronology

- ^ Britannica.com website, Serampore Trio

- ^ Google Books website, ‘’Religion and World Civilizations [3 volumes]: How Faith Shaped Societies’’ edited by Andrew Holt, page 295

- ^ William Carey's Less-than-Perfect Family Life, Christian History, Issue 36, 10 January 1992

- ^ Timothy George, The Life and Mission of William Carey, IVP, p. 158

- ^ The Senate of Serampore College

- ^ Culross, James (1882). William Carey. New York: A.C. Armstrong & Son. p. 190.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Carey.

- ^ Robert Eric Frykenberg and Alaine M. Low (2003), Christians and Missionaries in India, pp. 156–157, ISBN 978-0-8028-3956-5

- ^ a b Silvia Nagy (2010), Colonization Or Globalization?: Postcolonial Explorations of Imperial Expansion, p. 62, ISBN 978-073-91-31763

- ^ Frank Deauville Walker, William Carey (1925, repr. Chicago: Moody Press, 1980). ISBN 0-8024-9562-1.

- ^ a b Beck, James R. Dorothy Carey: The Tragic and Untold Story of Mrs. William Carey. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1992. ISBN 0-8010-1030-6.

- ^ "Dorothy's Devastating Delusions," Christian History & Biography, 1 October 1992.

- ^ Book Review - Dorothy Carey: The Tragic And Untold Story Of Mrs. William Carey Archived 15 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Missionaries of the World website, Hannah Marshmann, article dated July 4, 2011

- ^ Iain H. Murray, The Puritan Hope. Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1975. ISBN 0-85151-037-X.

- ^ "The Theology of William Carey," Evangelical Review of Theology 17 (1993): 369–80.

- ^ Yeh, Allan; Chun, Chris (2013). Expect Great Things, Attempt Great Things: William Carey and Adoniram Judson, Missionary Pioneers. Wipf and Stock. p. 13. ISBN 9781610976145.

- ^ Aalbertinus Hermen Oussoren, William Carey, Especially his Missionary Principles (Diss.: Freie Universität Amsterdam), (Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff, 1945).

- ^ E. Daniels Potts. British Baptist Missionaries in India 1793–1837: The History of Serampore and its Missions, (Cambridge: University Press, 1967).

- ^ D. James Kennedy, "William Carey: Texts That Have Changed Lives"[permanent dead link]: "It was the belief of these men that there was going to be ushered in by the proclamation of the Gospel a glorious golden age of Gospel submission on the part of the heathen. It is very interesting to note that theologically that is what is known as 'postmillennialism,' a view which is not very popular today, but was the view that animated all the men who were involved in the early missionary enterprise."

- ^ Thomas Schirrmacher, William Carey, Postmillennialism and the Theology of World Missions

- ^ a b "William Carey". 20 February 2024.

- ^ Smith, George (1885). The Life of William Carey, D.D.: Shoemaker and Missionary, Professor ..., Part 4. R & R Clark, Edinburgh. pp. 69–70.

- ^ Rao, Goparaju Sambasiva (1994). Language Change: Lexical Diffusion and Literacy. Academic Foundation. pp. 48 and 49. ISBN 978-81-7188-057-7. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014.

- ^ Carey, William (1805). A Grammar of the Marathi Language. Serampur: Serampore Mission Press. ISBN 978-1-108-05631-1.

- ^ Kopf, David (1969). British Orientalism and the Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1778–1835. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. pp. 71, 78.

- ^ Brockington, John (1991–1992). "William Carey's Significance as an Indologist" (PDF). Indologica Taurinensia. 17–18: 87–88. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- ^ Smith 1885, p. 150>

- ^ Smith 1885, p. 148>

- ^ Smith 1885, p. 102>

- ^ "William Carey". Christianity Today. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ Kopf, David (1969). British Orientalism and the Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1778–1835. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. pp. 70, 78.

- ^ Mangalwadi, Vishal (1999). The Legacy of William Carey: A Model for the Transformation of a Culture. Crossway Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-58134-112-6.

- ^ Yeh page=39

- ^ Yeh, Allan; Chun, Chris (2013). Expect Great Things, Attempt Great Things: William Carey and Adoniram Judson, Missionary Pioneers. Wipf and Stock. p. 117. ISBN 9781610976145.

- ^ "About William Carey". William Carey University. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Watson, Jeannie. "Reverend Isaac McCoy & the Carey Mission" (PDF). Michigan Genealogy on the Web. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ The Baptist Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. 1881. pp. 766–767. Retrieved 23 July 2024.

- ^ Cooper, Matthew. "The Carey Experience". Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "William Carey". Blue plaques. Leicester..

- ^ "Central Baptist Church and William Carey Museum". Visit Leicester. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "William Carey Museum". Central Baptist. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ "Center for Study of the Life and Work of William Carey". William Carey university.

References

[edit]- Chatterjee, Sunil Kumar. William Carey and Serampore, Calcutta, Ghosh publishing concern, 1984.

- Daniel, J.T.K.and Hedlund, R.E. (ed.). Carey's Obligation and Indian Renaissance, Serampore, Council of Serampore College, 1993.

- M.M. Thomas. Significance of William Carey for India today, Makkada, Marthoma Diocesan Centre, 1993.

- Beck, James R. Dorothy Carey: The Tragic and Untold Story of Mrs. William Carey. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1992.

- Carey, William. An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens. Leicester: A. Ireland, 1791.

- An Enquiry into the Obligations of Christians to Use Means for the Conversion of the Heathens at Project Gutenberg

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1887). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 9. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Farrer, Keith. (2005). William Carey – Missionary and Botanist. Carey Baptist Grammar School. Melbourne.

- Dutta, Sutapa. British Women Missionaries in Bengal, 1793–1861. U.K.: Anthem Press, 2017.

- Marshman, John Clark. Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward Embracing the History of the Serampore Mission. 2 vols. London: Longman, 1859.

- Murray, Iain. The Puritan Hope: Revival and the Interpretation of Prophecy. Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1971.

- Nicholls, Bruce J. "The Theology of William Carey." In Evangelical Review of Theology 17 (1993): 372.

- Oussoren, Aalbertinus Hermen. William Carey, Especially his Missionary Principles. Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff, 1945.

- Potts, E. Daniels. British Baptist Missionaries in India 1793–1837: The History of Serampore and its Missions. Cambridge: University Press, 1967.

- Smith, George. The Life of William Carey: Shoemaker and Missionary. London: Murray, 1887.

- The Life of William Carey: Shoemaker and Missionary at Project Gutenberg

- Walker, F. Deauville. William Carey: Missionary Pioneer and Statesman. Chicago: Moody, 1951.

Further reading

[edit]- Carey, Eustace - Memoir of William Carey, D. D. Late missionary to Bengal, Professor of Oriental Languages in the College of Fort William, Calcutta. Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln, 1836; 2nd edition: London: Jackson & Walford: 1837.

- Carey, S. Pearce - William Carey "The Father of Modern Missions", edited by Peter Masters, Wakeman Trust, London, 1993 ISBN 1-870855-14-0 (S. Pearce Carey was a grandson and prominent Baptist minister in Melbourne, Australia.)[1]

- Cule, W.E. - The Bells of Moulton, The Carey Press, 1942 (Children's biography)

- A Grammar of the Bengalee Language (1801)

- Kathopakathan [কথোপকথন] (i.e. "Conversations") (1801)

- Itihasmala [ইতিহাসমালা] (i.e. "Chronicles") (1812)

External links

[edit]- The Church of St John the Baptist, Piddington

- William Carey biographies Archived 14 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Center for the study of the life and work of William Carey, USA includes Works by and about Carey

- Works by William Carey at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Carey at the Internet Archive

- The William Carey Experience

- The Carey Exhibition, Central Baptist Church, Leicester

- Missionary Marriage Issues: What About Dorothy?

- ^ "Day by Day". The Methodist. Vol. XXXVI, no. 25. New South Wales, Australia. 18 June 1927. p. 3. Retrieved 22 October 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1761 births

- 1834 deaths

- English Baptist missionaries

- English Calvinist and Reformed Christians

- English evangelicals

- Baptist writers

- Translators of the Bible into Bengali

- Translators of the Bible into Telugu

- Translators of the Bible into Punjabi

- Translators to Sanskrit

- Clergy from Northampton

- Clergy from Leicester

- Shoemakers

- Social history of India

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges

- Anglican saints

- British missionary linguists

- 18th-century English Baptist ministers

- 19th-century English Baptist ministers

- British people in colonial India

- Baptist missionaries in India

- British missionary educators

- People from West Northamptonshire District

- Protestant missionaries in Asia

- Christian missionaries in India

- Protestantism in India

- Missionary botanists

- Christian revivalists

- Church Mission Society missionaries

- Scholars from West Bengal