Mount Adams (Washington)

| Mount Adams | |

|---|---|

| Pahto Klickitat | |

Mount Adams from the west-northwest | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 12,281 ft (3,743 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 8,116 ft (2,474 m)[2] |

| Isolation | 46.1 mi (74.2 km)[2] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 46°12′09″N 121°29′27″W / 46.202411792°N 121.490894694°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | John Adams |

| Geography | |

| Location | Yakama Nation / Skamania County, Washington, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Adams East |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | Less than 520,000 years |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 950 CE[3] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1854 by A.G. Aiken and party |

| Easiest route | South Climb Trail #183 |

Mount Adams, known by some Native American tribes as Pahto or Klickitat,[4] is an active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range.[5] Although Adams has not erupted in more than 1,000 years, it is not considered extinct. It is the second-highest mountain in Washington, after Mount Rainier.[6]

Adams, named for President John Adams, is a member of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, and is one of the arc's largest volcanoes,[7] located in a remote wilderness approximately 34 miles (55 km) east of Mount St. Helens.[8] The Mount Adams Wilderness consists of the upper and western part of the volcano's cone. The eastern side of the mountain is designated as part of the territory of the Yakama Nation.[9][10]

Adams' asymmetrical and broad body rises 1.5 miles (2.4 km) above the Cascade crest. Its nearly flat summit was formed as a result of cone-building eruptions from separated vents. The Pacific Crest Trail traverses the western flank of the mountain.[11][12]

Geography

[edit]General

[edit]

Mount Adams stands 37 miles (60 km) east of Mount St. Helens and about 50 miles (80 km) south of Mount Rainier. It is 30 miles (48 km) north of the Columbia River and 55 miles (89 km) north of Mount Hood in Oregon. The nearest major cities are Yakima, 50 miles (80 km) to the northeast, and the Portland metropolitan area, 60 miles (97 km) to the southwest. Between half and two thirds of Adams is within the Mount Adams Wilderness of the Gifford Pinchot National Forest. The remaining area is within the Mount Adams Recreation Area of the Yakama Indian Reservation. While many of the volcanic peaks in Oregon are located on the Cascade Crest, Adams is the only active volcano in Washington to be so. It is farther east than all the rest of Washington's volcanoes except Glacier Peak.[13]

Adams is one of the long-lived volcanoes in the Cascade Range, with minor activity beginning 900,000 years ago and major cone building activity beginning 520,000 years ago. The whole mountain has been completely eroded by glaciers to an elevation of 8,200 feet (2,500 m) twice during its lifetime. The current cone was built during the most recent major eruptive period 40,000–10,000 years ago.[14][15]

Standing at 12,281 feet (3,743 m), Adams towers about 9,800 feet (3,000 m) over the surrounding countryside. It is the second-highest mountain in Washington and third-highest in the Cascade Range. Because of the way it developed, it is the largest stratovolcano in Washington and second-largest in the Cascades, behind only Mount Shasta. Its large size is reflected in its 18 miles (29 km)-diameter base, which has a prominent north–south trending axis.[13]

Adams is the source of the headwaters for two major rivers, the Lewis River and White Salmon River. The many streams that emanate from the glaciers and from springs at its base flow into two more major river systems, the Cispus River and the Klickitat River. The streams on the north and west portions of Adams feed the Cispus River, which joins the Cowlitz River near Riffe Lake, and the Lewis River.[citation needed]

To the south, the White Salmon River has its source on the lower flanks of the west side of Adams and gains additional flows from streams along the southwest side of the mountain. Streams on the east side all flow to the Klickitat River. Streams on all sides, at some point in their courses, provide essential irrigation water for farming and ranching. The Klickitat and White Salmon rivers are nearly completely free flowing, with only small barriers to aid irrigation (White Salmon)[16] and erosion control (Klickitat).[17][18] The Cispus and Lewis rivers have been impounded with dams farther downstream for flood control and power generation purposes.[citation needed]

Mount Adams is the second-most isolated, in terms of access, stratovolcano in Washington; Glacier Peak is the most isolated. Only two major highways pass close to it. Highway 12 passes about 25 miles (40 km) to the north of Adams through the Cascades. Highway 141 comes within 13 miles (21 km) of Adams as it follows the White Salmon River valley up from the Columbia River to the small town of Trout Lake. From either highway, travelers have to use Forest Service roads to get closer to the mountain. The main access roads, FR 23, FR 82, FR 80, and FR 21, are paved for part of their length. Almost all other roads are gravel or dirt, with varying degrees of maintenance.[19][20] Access to the Mount Adams Recreation Area is by way of FR 82, which becomes BIA 285 at the Yakama reservation boundary. BIA 285 is known to be extremely rough and often suitable only for trucks or high-clearance vehicles.[21] Two small towns, Glenwood and Trout Lake, are located in valleys within 15 miles (24 km) of the summit, Glenwood on the southeast quarter and Trout Lake on the southwest quarter.[citation needed]

The mountain's size and distance from major cities, and the tendency of some people to forget or ignore Mount Adams, has led some people to call this volcano "The Forgotten Giant of Washington".[14]: 237

On a clear day from the summit, other visible volcanoes in the Cascade Range include: Mount Rainier, Mount Baker, and Glacier Peak to the north, as well as Mount St. Helens to the west, all in Washington; and Mount Hood, Mount Jefferson, and the Three Sisters, all to the south in Oregon.[22][23]

Summit area

[edit]Contrary to legend, the flatness of Adams' current summit area is not due to the loss of the volcano's peak. Instead, it was formed as a result of cone-building eruptions from separated vents. A false summit, Pikers Peak, rises 11,657 feet (3,553 m) on the south side of the nearly half-mile (800 m) wide summit area. The true summit is about 600 feet (180 m) higher on the gently sloping north side. A small lava and scoria cone marks the highest point. Suksdorf Ridge is a long buttress descending from the false summit to an elevation of 8,000 feet (2,000 m). This structure was built by repeated lava flows in the late Pleistocene. The Pinnacle forms the northwest false summit and was created by erosion from the Adams and White Salmon glaciers. On the east side, The Castle is a low prominence at the top of Battlement Ridge. The summit crater is filled with snow and is open on its west rim.[7]

Flank terrain features

[edit]Prominent ridges descend from the mountain on all sides. On the north side, the aptly named North Cleaver comes down from a point below the summit ice cap heading almost due north. The Northwest Ridge and West Ridge descend from the Pinnacle, to the northwest and west, respectively. Stagman Ridge descends west-southwest from a point about halfway up the west side and turns more southwest at about 6,000 feet (1,830 m). South of Stagman Ridge lies Crofton Ridge. Crofton gradually becomes very broad as it descends southwesterly from the tree line. MacDonald Ridge, on the south side, starts at about tree line below the lower end of Suksdorf Ridge and descends in a southerly direction.

Three prominent ridges descend from the east side of the mountain. The Ridge of Wonders is farthest south and ends at an area away from the mountain called The Island. Battlement Ridge is very rugged and descends from high on the mountain. The farthest ridge north on the east side, Victory Ridge, descends from a lower elevation on the mountain than Battlement Ridge beneath the precipitous Roosevelt Cliff. Lava Ridge, starting at about the same location as the North Cleaver, descends slightly east of north.[24][25]

Several rock prominences exist on the lower flanks of Adams. The Spearhead is an abrupt rocky prominence near the bottom of Battlement Ridge. Burnt Rock, The Hump, and The Bumper are three smaller rocky prominences at or below the tree line on the west side.[24][25]

Glaciers

[edit]

In the early 21st century, glaciers covered a total of 2.5% of Adams' surface. During the last ice age about 90% of the mountain was glaciated. Mount Adams has 209 perennial snow and ice features and 12 officially named glaciers. The total ice-covered area makes up 9.3 square miles (24 km2), while the area of named glaciers is 7.7 sq mi (20 km2).[26] Most of the largest remaining glaciers (including the Adams, Klickitat, Lyman, and White Salmon) originate from Adams' summit ice cap.[27][28]

On the northwest face of the mountain, Adams Glacier cascades down a steep channel in a series of icefalls before spreading out and terminating at around the 7,000 feet (2,130 m) elevation, where it becomes the source of the Lewis River and Adams Creek, a tributary of the Cispus River.[27] Its eastern lobe ends at a small glacial tarn, Equestria Lake. In the Cascades, Adams Glacier is second in size only to Carbon Glacier on Mount Rainier.[24][25][29][30]

The Pinnacle, White Salmon, and Avalanche glaciers on the west side of the mountain are less thick and voluminous, and are generally patchy in appearance. They all originate from glacial cirques below the actual summit. Although the White Salmon Glacier does not originate from the summit ice cap, it does begin very high on the mountain at about 11,600 feet (3,540 m). In the early 20th century, a portion of it descended from the summit ice cap,[28] but volume loss has separated it. Some of its glacial ice feeds the Avalanche Glacier below it to the southwest while the rest tumbles over some large cliffs to its diminutive lower section to the west. The White Salmon and Avalanche Glaciers feed the many streams of the Salt Creek and Cascade Creek drainages, which flow into the White Salmon River. The Pinnacle Glacier is the source of a fork of the Lewis River as well as Riley Creek, which is also a tributary of the Lewis River.[24][25][30]

The south side of the mountain along Suksdorf Ridge is moderately glacier-free, with the only glaciers being the relatively small Gotchen Glacier and the Crescent Glacier. The south side, however, does have some perennial snowfields on its slopes. The Crescent Glacier is the source of Morrison Creek; and, although it does not feed it directly, the Gotchen Glacier is the source of Gotchen Creek. Both creeks drain to the White Salmon River.[25][30]

The rugged east side has four glaciers, the Mazama Glacier, Klickitat Glacier, Rusk Glacier, and the Wilson Glacier. During the last ice age, they carved out two immense canyons: the Hellroaring Canyon and the Avalanche Valley. This created the Ridge of Wonders between the two. Of the four glaciers on the east side, the Mazama Glacier is the farthest south and begins between the Suksdorf Ridge and Ridge of Wonders at about 10,500 feet (3,200 m). Near its terminus, it straddles the Ridge of Wonders and a small portion feeds into the Klickitat Glacier. The glacier gains more area from additional glacier ice that collects from drifting snow and avalanches below the Suksdorf Ridge as the ridge turns south. The Mazama Glacier terminates at about 8,000 feet (2,440 m) and is the source of Hellroaring Creek, which flows over several waterfalls before it joins Big Muddy Creek. Klickitat Glacier on the volcano's eastern flank originates in a 1 mile (1.6 km) wide cirque and is fed by two smaller glaciers from the summit ice cap. It terminates around 6,600 feet (2,010 m), where it becomes the source of Big Muddy Creek, a tributary of the Klickitat River. The Rusk Glacier does not start from the summit ice cap but starts at 10,500 feet (3,200 m) below the Roosevelt Cliff and is fed by avalanching snow and ice from the summit cap. It is enclosed on the south by Battlement Ridge and Victory Ridge on the north and terminates at about 7,100 feet (2,160 m). It is the source of Rusk Creek, which flows over two waterfalls before joining the Big Muddy on its way to the Klickitat. The Wilson Glacier, like the Rusk Glacier, starts below the Roosevelt Cliff and is fed by avalanching snow and ice; however, the Wilson Glacier starts slightly higher at about 10,800 feet (3,290 m). It is also fed by an arm of the Lyman Glacier as it flows down from the summit ice cap. The Wilson Glacier terminates at 7,500 feet (2,290 m) where it is the source of Little Muddy Creek, another tributary of the Klickitat.[25][30]

The north side is distinguished by two major glaciers, the Lyman and Lava Glaciers. Like the Adams Glacier, the Lyman Glacier is characterized by deep crevasses and many icefalls as it cascades down from the summit ice cap.[27] It is divided into two arms by a very rugged ridge at 10,200 feet (3,110 m) and terminates at 7,400 feet (2,260 m). The Lava Glacier originates in a large cirque below the summit at about 10,000 feet (3,050 m), sandwiched between the North Cleaver on the west and the Lava Ridge to the east. It terminates at about 7,600 feet (2,320 m). The Lava and Lyman Glaciers are the source of the Muddy Fork of the Cispus River.[25][26][30]

The total glacier area on Mount Adams decreased 49%, from 12.2 square miles (31.5 km2) to 6.3 square miles (16.2 km2), between 1904 and 2006, with the greatest loss occurring before 1949. Since 1949, the total glacier area has been relatively stable with a small amount of decline since the 1990s.[30][31]

Surrounding area

[edit]

Mount Adams is surrounded by a variety of other volcanic features and volcanoes. It stands near the center of a north–south trending volcanic field that is about 4 miles (6.4 km) wide and 30 miles (48 km) long, from just south of the Goat Rocks to Guler Mountain, the vent farthest south in the field. This field includes over 120 vents; about 25 of these are considered flank volcanoes of Mount Adams. The largest flank volcano is a basaltic shield volcano on Adams east base called Goat Butte. This structure is at least 150,000 years old. Little Mount Adams is a symmetrical cinder cone on top of the Ridge of Wonders on Adams' southeast flank.[32]

Potato Hill is a cinder cone on Adams' north side that was created in the late Pleistocene and stands 800 feet (240 m) above its lava plain.[33]

Lavas from its base flowed into the Cispus Valley where they were later modified by glaciers. At the 7,500 feet (2,290 m) level on Adams' south flank is South Butte. The lavas associated with this structure are all younger than Suksdorf Ridge but were emplaced before the end of the last ice age.[33]

Several relatively young obvious lava flows exist in the area around Adams. Most of these flows are on the north side of the mountain and include the flow in the Mutton Creek area, Devils Garden, the Takh Takh Meadows Flow, and the much larger Muddy Fork Lava Flow to the north of Devils Garden. Only one obvious flow appears on the south slopes of Adams, the A. G. Aiken Lava Bed. Other smaller flows exist in various locations around the mountain as well.[14]

The many other vents and volcanoes encompassed by the Mount Adams field include Glaciate Butte and Red Butte on the north, King Mountain, Meadow Butte, Quigley Butte, and Smith Butte on the south, with others interspersed throughout.[14]

Located about 25 miles (40 km) north of Adams is Goat Rocks Wilderness and the heavily eroded ruins of a stratovolcano that is much older than Adams. Unlike Adams, the Goat Rocks volcano was periodically explosive and deposited ash 2.5 million years ago that later solidified into 2,100-foot (640 m) thick tuff layers.[34]

In the area surrounding Mount Adams, many caves have formed around inactive lava vents.[23] These caves, usually close to the surface, can be hundreds of feet (meters) deep and wide.[35] A few of the more well known caves include the Cheese Cave, Ice Cave, and Deadhorse Caves. Cheese Cave has the largest bore of the caves near Adams with a diameter of 40–50 feet (12–15 m) and a length of over 2,000 feet (610 m).[36] Ice cave, which is made up of several sections created by several sinkholes, has an ice section that is 120 feet (37 m) long and 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m) in diameter and noted for its ice formations.[37][38] From the same entrance, the tube continues another 500 feet (150 m) to the west.[39][40] Deadhorse Cave is a massive network of lava tubes. It is the most complex lava tube in the United States with 14,441 feet (4,402 m) of passage.[41] These caves are all just outside of Trout Lake. These and many other caves in the Trout Lake area were at one time part of a huge system that originated at the Indian Heaven volcanic field. The most obscure caves around Adams are the Windholes on the southeast side near Island Cabin Campground.[42]

Geology

[edit]

Adams is made of several overlapping cones that together form an 18-mile-diameter (29 km) base which is elongated in its north–south axis and covers an area of 250 square miles (650 km2). The volcano has a volume of 70 cubic miles (290 km3) placing it second only to Mount Shasta in that category among the Cascade stratovolcanoes.[7] Mount Adams was created by the subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate, which is located just off the coast of the Pacific Northwest.[14]

Mount Adams was born in the mid- to late Pleistocene and grew in several pulses of mostly lava-extruding eruptions. Each eruptive cycle was separated from one another by long periods of dormancy and minor activity, during which, glaciers eroded the mountain to below 9,000 feet (2,700 m). Potassium-argon dating has identified three such eruptive periods; the first occurring 520,000 to 500,000 years ago, the second 450,000 years ago, and the third 40,000 to 10,000 years ago.[14] Most of these eruptions and therefore most of the volcano, consist of lava flows with little tephra. The loose material that makes up much of Adams' core is made of brecciated lava.[7]

Andesite and basalt flows formed a 20-to-200-foot (6 to 60 m) thick circle around the base of Mount Adams, and filled existing depressions and ponded in valleys. Most of the volcano is made of andesite together with a handful of dacite and pyroclastic flows which erupted early in Adams' development. The present main cone was built when Adams was capped by a glacier system in the last ice age. The lava that erupted was shattered when it came in contact with the ice and the cone interior is therefore made of easily eroded andesite fragments. Since its construction, constant emissions of heat and caustic gases have transformed much of the rock into clays (mostly kaolinite), iron oxides, sulfur-rich compounds and quartz.[43]

The present eruptive cone above 7,000 feet (2,100 m) was constructed sometime between 40,000 to 10,000 years ago. Since that time the volcano has erupted at least ten times, generally from above 6,500 feet (2,000 m). One of the more recent flows issued from South Butte and created the 4.5-mile (7.2 km) long by 0.5-mile (0.8 km) wide A.G. Aiken Lava Bed. This flow looks young but has 3,500-year-old Mount St. Helens ash on it, meaning it is at least that old.[5] Of a similar age are the Takh Takh Meadows and Muddy Fork lava flows. The lowest vent to erupt since the main cone was constructed is Smith Butte on the south slope of Adams. The last lava known to have erupted from Adams is an approximately 1000-year-old flow that emerged from a vent at about 8,200 feet (2,500 m) on Battlement Ridge.[14]

The Trout Lake Mudflow is the youngest large debris flow from Adams and the only large one since the end of the last Ice Age. The flow dammed Trout Creek and covered 25 miles (40 km) of the White Salmon River valley. Impounded water later formed Trout Lake. The Great Slide of 1921 started close to the headwall of the White Salmon Glacier and was the largest avalanche on Adams in historic time. The slide fell about 1 mile (1.6 km) and its debris covered about 1 square mile (2.6 km2) of the upper Salt Creek area.[44] Steam vents were reported active at the slide source for three years, leading to speculation that the event was started with a small steam explosion.[43] This was the only debris flow in Mount Adams' recorded history, but there are five known lahars.[45]

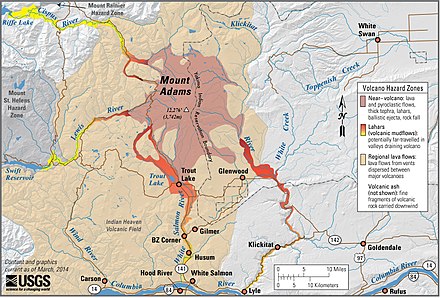

Since then, thermal anomalies (hot spots) and gas emissions (including hydrogen sulfide) have occurred especially on the summit plateau and indicate that Adams is dormant, not extinct. Future eruptions from Adams will probably follow patterns set by previous events and will thus be flank lava flows of andesite or basalt. Because the primary products were andesite, the eruptions that occur on Adams tend to have a low to moderate explosiveness and present less of a hazard than the violent eruptions of St. Helens and some of the other Cascade volcanoes. However, since the interior of the main cone is little more than a pile of fragmented lava and hydrothermally altered rock, there is a potential for very large landslides and other debris flows.[43]

In 1997, Adams experienced two slides seven weeks apart that were the largest slides in the Cascades, ignoring the catastrophic landslide eruption of Mount St. Helens, since a slide that occurred on Little Tahoma in 1963.[46] The first occurred at the end of August and consisted of mainly snow and ice with some rock. It fell from a similar location and in a similar path to the slide of 1921. The second slide that year occurred in late October and originated high on Battlement Ridge just below The Castle. It consisted of mainly rock and flowed three miles down the Klickitat Glacier and the Big Muddy Creek streambed. Both slides were estimated to have moved as much as 6.5 million cubic yards (5.0 million cubic meters) of material.[14]

The Indian Heaven volcanic field is located between St. Helens and Adams and within the Indian Heaven Wilderness. Its principal feature is an 18-mile (29 km) long linear zone of shield volcanoes, cinder cones, and flows with volumes of up to </ref>t|23|cumi|km3}} with the highest peak, Lemei Rock. The shield volcanoes, which form the backbone of the volcanic field, are located on the northern and southern sides of the field. Mount St. Helens and Mount Adams are on the western and the eastern sides.[29]

To the east, across the Klickitat River, lies the Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. This area contains many small shield volcanoes and cinder cones of mainly alkalic intraplate basalt with fractionated intermediate alkalic products, subordinate subalkaline mafic lavas, and several rhyolites as secondary products. There are about 205 vents that were active between 4.2 million and 600 thousand years ago.[15]

Seismic activity around Adams is very low and it is one of the quietest volcanoes in Oregon and Washington. It is monitored by the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and the Cascades Volcano Observatory via a seismic station on the southwest flank of the mountain.[47]

During the month of September of 2024, the U.S. Geological Survey Cascades Volcano Observatory recorded six earthquakes ranging in magnitudes 0.9 to 2.0. With a normal rate of one earthquake every 2-3 years, this is above background levels, and the most since recordkeeping began in 1982. The USGS plans to install temporary seismic stations around Mount Adams to better estimate the size and depth of these earthquakes.[48][49][50]

Recreation

[edit]

Like many other Cascade volcanoes, Mount Adams offers many recreational activities, including mountain climbing, backcountry skiing, hiking and backpacking, berry picking, camping, boating, fishing, rafting, photography, wildlife viewing, and scenic driving among other things.[9][51]

The 47,122-acre (19,070 ha)[52] Mount Adams Wilderness along the west slope of Mount Adams offers an abundance of opportunities for hiking, backpacking, backcountry camping, mountain climbing and equestrian sports. Trails in the wilderness pass through dry east-side and moist west-side forests, with views of Mt. Adams and its glaciers, tumbling streams, open alpine forests, parklands, and a variety of wildflowers among lava flows and rimrocks.[9] A Cascades Volcano Pass from the United States Forest Service (USFS) is required for activities above 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from June through September.[53]

On the north side, the Midway High Lakes Area, which lies mostly outside the wilderness area, is one of the more popular areas around Mount Adams. The area is made up of four large lakes, Council Lake, Takhlakh Lake, Ollalie Lake, and Horseshoe Lake; one small lake, Green Mountain Lake; and a group of small lakes, Chain of Lakes. The area offers developed and primitive camping as well as a good number of trails for hiking and backpacking. Most trails are open to horses and many outside the wilderness are open to motorcycles. More scenery similar to what is encountered in the Mount Adams Wilderness abounds. The area also offers boating and fishing opportunities on several of the lakes.[19][54]

On the south side of Adams, the Morrison Creek area provides additional opportunities for hiking, backpacking, biking, and equestrian sports with several long loop trails. A few small and primitive campgrounds exist in the area, including the Wicky Creek Shelter. Generally, there are trailheads at these campgrounds.[20]

On the southeast side of the mountain, the Mount Adams Recreation Area, another very popular area, offers activities such as hiking, camping, picnicking, and fishing. The area features Bird Creek Meadows, a popular picnic and hiking area noted for its outstanding display of wildflowers,[55] and exceptional views of Mount Adams and its glaciers, as well as Mount Hood to the south.[56] Some areas of the Yakama Indian Reservation are open for recreation, while other areas are open only to members of the tribe.[21]

Climbing

[edit]

Each year, thousands of outdoor enthusiasts attempt to summit Mount Adams. The false summits and broad summit plateau have disheartened many climbers as this inscription on a rock at Piker's Peak indicates. "You are a piker if you think this is the summit. Don't crab, the mountain was here first."[57] Crampons and ice axes are needed on many routes because of glaciers and the route's steepness. Aside from crevasses on the more difficult glacier routes, the biggest hazard is the loose rocks and boulders which are easily dislodged and a severe hazard for climbers below. These falling rocks are especially dangerous for climbers on the precipitous east faces and the steep headwalls of the north and west sides. Routes in those areas should only be climbed early in the season under as ideal conditions as can be had. Other hazards faced by climbers on Adams include sudden storms and clouds, avalanches, altitude sickness, and inexperience. Climbing Mount Adams can be dangerous for a variety of reasons and people have died in pursuit of the summit while many others have had close calls.[57][58][59][60]

Routes

[edit]There are 25 main routes to the summit with alternates of those main routes.[52] They range in difficulty from the relatively easy non-technical South Spur (South Climb) route to the extremely challenging and dangerous Victory Ridge, Rusk Glacier Headwall, and Wilson Glacier Headwall routes up Roosevelt Cliff.[60][61]

| Route Name | Grade (YDS, AIRS) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| South Spur (South Climb) | I | Most popular route on Adams; non-technical; first climbed in 1863 or 1864 |

| Southwest Chute | I | Steep scree or snow climb; first climbed in 1965 |

| Avalanche Glacier Headwall | I | Steep scree or snow climb; first climbed in 1976 |

| Avalanche-White Salmon Glacier | I | Moderate glacier and scree climb; first climbed in 1957 |

| West Ridge | I, Class 2 | Steep ridge climb; first climbed in 1963 |

| Pinnacle Glacier Headwall | II, Class 4 | Steep unstable rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1965 |

| Northwest Ridge | II | Steep ridge climb; first climbed in 1924 |

| North Face of Northwest Ridge | II | Steep rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1967 |

| Adams Glacier to NW Ridge | II, AI2 | Steep rock and glacier climb |

| Adams Glacier | II, AI2 | Classic, difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1945 |

| Stormy Monday Couloir | III, Class 4–5 | Steep unstable rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1975 |

| North Ridge Headwall | II, Class 4 | Steep unstable rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1960 |

| North Cleaver | II, Class 2–3 | Steep ridge climb; likely route of first ascent in 1854 |

| Lava Glacier Headwall West | II, Class 4 | Steep unstable rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1965 |

| Lava Glacier Headwall East | II, Class 4 | Steep unstable rock or snow climb; first climbed in 1960 |

| Lava Ridge | II, Class 2–3 | Steep ridge climb; first climbed in 1961 |

| Lyman Glacier North Arm | II, AI2 | Difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1948 |

| Lyman Glacier South Arm | III, AI2 | Difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1966 |

| Wilson Glacier | III, AI2 | Difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1961 |

| Wilson Glacier Headwall | IV, Class 4 | Very steep, unstable rock and glacier climb; first climbed in 1961 |

| Victory Ridge | IV-V, Class 4–5 | Very steep, unstable rock and glacier climb; first climbed in 1962 |

| Rusk Glacier Headwall | IV, Class 4 | Very steep, unstable rock and glacier climb; first climbed in 1978 |

| Battlement Ridge | III, Class 3–4 | Steep glacier and unstable rock climb; first climbed in 1921[59] |

| South Side of Battlement Ridge | III, Class 3–4 | Steep unstable rock climb; first climbed in 1934 |

| Klickitat Glacier | III, Class 3–4, AI2 | Difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1938 |

| Klickitat Headwall | III, Class 3–4, AI2 | Steep unstable rock and ice climb; first climbed in 1971 |

| South Klickitat Glacier | III, Class 3–4, AI2 | Difficult, steep glacier climb; first climbed in 1962 |

| Mazama Glacier | I | Easy glacier climb |

| Mazama Glacier Headwall | II, AI2 | Shorter, more direct alternate from the Mazama Glacier route |

Hiking

[edit]While the summit is the main draw for many who visit Adams,[citation needed] many trails pass through the area around Mount Adams where visitors can find extensive vistas, local history, displays of wildflowers, lava formations, and several waterfalls.

One such trail is the unofficially named "Round the Mountain Trail" that encircles Mount Adams and is approximately 35 miles (56 km) long.[62] It is called the "Round the Mountain Trail" unofficially because it is made up of three different named trails and an area where there is no trail. The 8–10 miles (13–16 km) section of the trail on the Yakama Indian Reservation may require special permits.[62]

Many trails access the "Round the Mountain Trail" in the Mount Adams Wilderness. On the south, the Shorthorn Trail #16 leaves from near the Morrison Creek Campground, and the South Climb Trail #183 starts at Cold Springs Trailhead/Campground and heads up the South Spur, the most popular climbing route to the summit. On the west side, there are three trails going up: the Stagman Ridge Trail #12, Pacific Crest Trail #2000, and the Riley Creek Trail #64. There are four trails providing access to the "Round the Mountain Trail" on the north side: the Divide Camp Trail #112, Killen Creek Trail #113, Muddy Meadows Trail #13, and the Pacific Crest Trail again as it heads down the mountain to the north. These trails accessing the "Round the Mountain Trail" generally gain between 1,500 feet (460 m) and 3,000 feet (910 m) in between 3 miles (4.8 km) and 6 miles (9.7 km). Trails are mostly snow-covered from early winter until early summer. Other popular trails in the Mount Adams Wilderness include the Lookingglass Lake Trail #9A, High Camp Trail #10, Salt Creek Trail #75, Crofton Butte Trail #73, and the Riley Connector Trail #64A.[9][20][63]

In the Mount Adams Recreation Area, many of the trails are geared toward leisurely walks and are located in the Bird Creek Meadows area. There are many loop trails at Bird Creek Meadows, including the Trail of the Flowers #106 in the main picnic area. Trails travel through meadows and past cold mountain streams and waterfalls, including Crooked Creek Falls.[64][65] Hikers can access the Hellroaring Overlook, where they can view Hellroaring Meadows, a glacial valley about 1,000 feet (300 m) down from the viewpoint precipice. From here, hikers can gaze up 5,800 feet (1,800 m) at Mount Adams, the Mazama Glacier, and various waterfalls tumbling off of high cliffs below the glaciers terminus.[66] Little Mount Adams 6,821 ft (2,079 m), a symmetrical cinder cone on top of the Ridge of Wonders, rises from the northeast end of Hellroaring Meadow and the Hellroaring Creek valley. A trail used to ascend from Bench Lake at the bottom of the canyon to the east base of the peak,[63] but this trail has recently been abandoned.[21] To reach the top, hikers must traverse rocky terrain; and if they exist, user-made trails.[21][63][67]

High Lakes Trail #116, the namesake of the Midway High Lakes Area, crosses the relatively flat area on the north side of the mountain following a trail the Yakama Native Americans used for picking huckleberries. Like several other trails around Adams, this trail has extensive views of the mountain. Other trails, like the Takh Takh Meadows Trail #136, pass through meadows and old lava flows. One of the longest trails on the Gifford Pinchot, Boundary Trail #1, has its eastern terminus in the Midway High Lakes area at Council Lake. Other trails in the area include the Council Bluff Trail #117, Green Mountain Trail #110, and East Canyon Trail #265.[19][63]

Several long trails pass through the Morrison Creek area on the south side of the mountain. The Snipes Mountain Trail #11 follows the eastern edge of the A.G. Aiken Lava Bed from the lower end for 6 miles (9.7 km) to the Round the Mountain Trail. The Cold Springs Trail #72 follows the western edge for 4 miles (6.4 km). Other trails in the area include the Gotchen Trail #40, Morrison Creek Trail #39, and Pineway Trail #71.[20][63]

Camping

[edit]

Campgrounds near Mount Adams are open during the snow-free months of summer. Campgrounds in the area include the Takhlakh Lake Campground, offering views across the lake of Mount Adams; Olallie Lake; Horseshoe Lake; Killen Creek; Council Lake; and Keenes Horse Camp. Adams Fork Campground and Twin Falls Campground are located along the Lewis and Cispus Rivers. Most lakes within the Midway High Lakes Area offer scenic views of Mount Adams and its glaciers.[51] Adams Fork Campground, Cat Creek Campground, and Twin Falls Campground are located nearer to Mount Adams and are just a few of the many campgrounds along the scenic Lewis and Cispus Rivers.[19]

The Morrison Creek area has three designated campgrounds: Morrison Creek Campground, Mount Adams Horse Camp, and the Wicky Creek Shelter. Many climbers also camp at the Cold Springs Trailhead.[20]

There are three campgrounds in the Mount Adams Recreation Area. A campground is located at Bird Lake, Mirror Lake, and Bench Lake. Bench Lake is the largest campground of the three and has excellent views up the Hellroaring Canyon.[21]

Farther down the southeast slope of Adams, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has two campgrounds along Bird Creek: Bird Creek Campground and Island Cabin Campground. Island Cabin is also used in winter by snowmobilers.[68]

Several of the campgrounds in the National Forest and all campgrounds in the Mount Adams Recreation Area require fees.[19][20][21] The campgrounds on DNR lands require a Discover Pass.[68]

Winter recreation

[edit]For winter recreation, there are a number of Washington state sno-parks on the south side that are popular with snowmobilers and cross-country skiers. There are three sno-parks on Mount Adams south slope: Snow King, Pineside, and Smith Butte Sno-parks. The south side of the mountain, especially the A.G. Aiken Lava Bed, is especially popular with snowmobilers and skiers. The Mount Adams Recreation Highway (FR 80) is plowed all the way to Pineside and Snow King Sno-parks at about 3,000 feet (910 m) elevation for most of the year, as long as there is enough money in the Forest Service's winter budget. Smith Butte Sno-park, at about 4,000 feet (1,200 m), is accessible in low-snow years. Most of the time, the road is not plowed all the way to Smith Butte. The U.S. Forest Service does this to not dry up the forest service's snowplowing funds.[9][20]

While the south side has several sno-parks near Adams, the north side has only one nearby, the Orr Creek Sno-park. This sno-park provides winter access to the Midway High Lakes Area. All the sno-parks in the area require a Washington state Sno-Park Permit.[19]

History

[edit]

Native American legends

[edit]Native Americans in the area have composed many legends concerning the three "smoking mountains" that guard the Columbia River. According to the Bridge of the Gods tale, Wy'east (Mount Hood) and Pahto (Mount Adams, also called Paddo or Klickitat by Native peoples) were the sons of the Great Spirit. The brothers both competed for the love of the beautiful La-wa-la-clough (Mount St. Helens). When La-wa-la-clough chose Pahto, Wy'east struck his brother hard so that Pahto's head was flattened and Wy'east took La-wa-la-clough from him (thus attempting to explain Adams' squat appearance).[14] Other versions of the story state that losing La-wa-la-clough caused Pahto such grief that he dropped his head in shame.[69][70][71]

In a Klickitat legend, the chief of the gods, Tyhee Saghalie, came to The Dalles with his two sons. The sons quarreled about who would settle where. To settle the dispute, Saghalie shot an arrow to the west and to the north and told his sons to find them and to settle where the arrows had fallen. So one settled in the Willamette Valley and the other in the area between the Yakima and Columbia Rivers and they became the ancestors of the Multnomah and Klickitat tribes respectively. To separate the tribes, Saghalie raised the Cascade Mountains. He also created the "Bridge of the Gods" as a way for the tribes to meet with one another easily. A "witch-woman," whose name was Loowit, lived on the bridge and had control of the only fire in the world. She wanted to give the tribes fire to improve their condition and Saghalie consented. He was so pleased with Loowit's faithfulness that he offered Loowit whatever she wanted. She asked for youth and beauty and Saghalie granted her wish. Suitors came from near and far until finally she could not decide between Klickitat and Wiyeast. Klickitat and Wiyeast went to war over the matter until finally Sahalie decided to punish them for creating such chaos. He broke the Bridge of the Gods and put the three lovers to death. However, to honor their beauty, he raised up three mountains: Wiyeast (Hood), Klickitat (Adams), and Loowit (St. Helens).[27][72][73][74][75]

In a similar legend from the Klickitats, there was a large inland sea between the Cascades and the Rocky Mountains. The Native Americans lived on the sea and each year they would hold two large powwows at Mount Multnomah, one in the spring and one in the fall. The demigod Koyoda Spielei lived among them and settled disputes among the living things of the earth, including the mountains Pa-toe (Adams) and Yi-east (Hood), sons of the Great Spirit Soclai Tyee. For many years, peace prevailed over the land. Then a beautiful female mountain moved to the valley between Pa-toe and Yi-east. She fell in love with Yi-east, but liked to flirt with Pa-toe. This caused the two mountains to quarrel with each other and it quickly escalated into an all-out brawl. Ignoring Koyoda's calls for peace, they belched forth smoke and ash and threw hot rocks at each other. Sometime later, they paused for a rest and discovered the catastrophe they had caused. The forests and meadows had been burnt to the ground and many animals and other living things had been killed. The earth had been shaken so severely that a hole had been created in the mountains and the sea had drained away and the Bridge of the Gods was formed. The female mountain had hid herself in a cave during the battle and because they could no longer find her, they were about to resume fighting. However, while they had been fighting, Koyoda went to Soclai and told him what was happening. Soclai arrived in time to stop them from resuming their quarrel. He decreed that the female mountain should remain in the cave forever and the Bridge of the Gods was to be a covenant of peace between the mountains that he would cause to fall if they ever resumed their quarrel. He also placed an ugly old woman, known as Loo-wit, as a mountain to guard the bridge and remind the brothers that beauty is never permanent. After many years, the signs of the great battle and the evidence of the inland sea had disappeared and there was happiness and contentment over the earth. The female mountain wished to come out of her cave and grew very lonely. To ease her loneliness, Soclai sent the Bats, a tribe of beautiful birds, to be her companions. Yi-east eventually learned that the Bats were her guardians and carried out secret communication with the female mountain through them. He befriended Loo-wit and crossed the bridge at night to meet with the female mountain. One night, he stayed too long and had to hurry to get back to his proper place. He caused the ground to shake so much in his haste that a large rock fell and blocked the entrance to the cave. When Soclai found this, he was furious with the Bats and punished them by turning them into bats that are seen today. He allowed the female mountain to remain out of the cave on her promise to be good, but would not allow her and Yi-east to be married, fearing the inevitable quarrel that might start again. He did promise to look for a mate for Pa-toe, hoping this would initiate a lasting peace. However, because of his many duties, he forgot this promise, and the two mountains were only held in check by his threats. Eventually, when Soclai was in another part of the world, they resumed their quarrel and created chaos again. Their violence broke the Bridge of the Gods and destroyed the landscape again. Loo-wit, in her attempts to stop the two brothers, was badly burned and scarred; and when the bridge collapsed, she fell with it. Finally, Pa-toe won the battle and Yi-east admitted defeat. Soclai returned from where he had been, but he was too late to avert the disaster. He found Loo-wit and because she had been faithful in her guardianship, he rewarded her by giving her her greatest desire, youth, and beauty. Having received this gift, she moved to the west side of the Cascades and remains there to this day as Mount St. Helens. Since Pa-toe won the battle, the female mountain belonged to him. She was heartbroken but took her place at his side. She soon fell at his feet and into a deep sleep from which she never awoke. She is now known as Sleeping Beauty. Pa-toe became so sad that he caused her deep sleep, he lowered his own head in remorse.[76]

The Yakamas also have a legend attempting to explain Adams' squat appearance. Long ago, the Sun was a man and he had five wives who were mountains: Plash-Plash (the Goat Rocks), Wahkshum (the Simcoe Mountains), Pahto (Adams), Rainier, and St. Helens. Because she was the third wife to be greeted by the Sun in the morning, Pahto became jealous. She broke down both Plash-Plash and Wahkshum, but left Rainier and St. Helens alone. She was happy that she was now the first to be greeted, but wanted more, so she crossed the Columbia and took plants and animals from the mountains there. The other mountains were afraid of her, but Klah Klahnee (the Three Sisters) convinced Wyeast (Hood) to confront Pahto. Wyeast initially tried being nice, but Pahto would have none of it. So Wyeast hit her head and knocked it off, creating Devils Garden. Wyeast then shared what Pahto had taken with the rest of the mountains. After this, Pahto became mean and she would send thunderstorms, heavy rain, and snow to the valleys below. The Great Spirit had been watching all this time and came to Pahto. He gave her a new head in the form of White Eagle and his son Red Eagle and he reminded her that she was his daughter. Pahto repented and promised to stop being mean and greedy.[77]

In many of the legends of the Cascade Mountains, there are thunderbirds that live on them and Adams is no exception. This particular thunderbird was named Enumtla and he terrorized the inhabitants of the land. Speelyi, the Klickitat coyote god, came along one day and they implored him to do something. Speelyi transformed himself into a feather and waited. It did not take long for Enumtla to see the feather and investigate. Being suspicious, he thundered at the feather with no effect. He paused and suddenly the magic feather let loose a terrific volley of thunder and lightning and stunned Enumtla. Speelyi then managed to overpower Enumtla and decreed that the thunderbird could no longer terrify the people, could only thunder on hot days, and could not destroy with lightning.[72]

Several other tribes have legends involving battles and disagreements between the great peaks. The Cowlitz and Chehalis have a legend where Rainier and St. Helens were female mountains and quarreled over Adams, the male mountain. In a different legend from the Cowlitz, St. Helens was the man and Pahto (Adams) and Takhoma (Rainier) were his wives and the two wives quarreled with each other. A thunderbird legend from the Yakamas has a terrific battle between the thunderbird, Enumklah, and his five wives, Tahoma (Rainier), Pahto (Adams), Ah-kee-kun (Hood), Low-we-lat-Klah (St. Helens), and Simcoe. Pahto and Tahoma were badly beaten, Ah-kee-kun and Low-we-lat-Klah escaped without injury, and Simcoe suffered the greatest injury for starting the battle.[78]

Exploration

[edit]Adams was known to the Native Americans as Pahto (with various spellings) and Klickitat. In various tribal languages (Plateau Penutian, Chinookan, Salishan), Pahto means high up, very high, standing up, or high sloping mountain.[79][80] The Klickitat name is of Klickitat origin and comes from the Chinookan for beyond.

In 1805, on the journey westward down the Columbia, the Lewis and Clark Expedition recorded seeing the mountain; noting that it was "a high mountain of emence hight covered with snow"[81] and thought it "perhaps the highest pinnacle in America."[27][81] They initially misidentified it as Mount St. Helens, which had been previously discovered and named by George Vancouver. On the return journey in 1806, they recorded seeing both, but did not give Adams a name, only calling it "a very high humped mountain".[81] This is the earliest recorded sighting of the volcano by European explorers.[81]

For several decades after Lewis and Clark sighted the mountain, people continued to get Adams confused with St. Helens, due in part to their somewhat similar appearance and similar latitude. In the 1830s, Hall J. Kelley led a campaign to rename the Cascade Range as the President's Range and rename each major Cascade mountain after a former President of the United States. Mount Adams was not known to Kelley and was thus not in his plan. Mount Hood, in fact, was designated by Kelley to be renamed after President John Adams and St. Helens was to be renamed after George Washington. In a mistake or deliberate change by mapmaker and proponent of the Kelley plan, Thomas J. Farnham, the names for Hood and St. Helens were interchanged. And, likely because of the confusion about which mountain was St. Helens, he placed the Mount Adams name north of Mount Hood and about 40 miles (64 km) east of Mount St. Helens. By what would seem sheer coincidence, there was in fact a large mountain there to receive the name. Since the mountain had no official name at the time, Kelley's name stuck even though the rest of his plan failed.[13] However, it was not official until 1853, when the Pacific Railroad Surveys, under the direction of Washington Territory governor Isaac I. Stevens, determined its location, described the surrounding countryside, and placed the name on the map.[14][27][60][80][82]

Since its discovery by explorers, the height of Adams has also been subject to revision. The topographer for the Pacific Railroad Surveys, Lt. Johnson K. Duncan, and George Gibbs, ethnologist and naturalist for the expedition, thought it was about the same height as St. Helens. Its large, uneven size apparently contributed to the underestimation.[60] The Northwest Boundary Survey listed Adams as having an elevation of 9,570 feet (2,920 m)[60] while a later United States Coast and Geodetic Survey gave it an elevation of 11,906 feet (3,629 m).[83] The height was more closely determined in 1895 by members of the Mazamas mountaineering club, William A. Gilmore, Professor Edgar McClure, and William Gladstone Steel. Using a boiling point thermometer, mercurial barometer, and an aneroid barometer, they determined the elevation to be 12,255, 12,402, and 12,150 feet (3,735, 3,780, and 3,703 m) respectively.[84] None of these numbers were used on any map because that same year, 1895, the US Geological Survey (USGS), using a triangulation method, also measured the height of several mountains in the Cascades and they measured Adams as having an elevation of 12,470 feet (3,800 m).[85] The USGS further refined their measurement sometime in late 1909 or early 1910 to 12,307 feet (3,751 m) and again in 1970 to 12,276 feet (3,742 m) for the release of the Mount Adams East 1:24000 quadrangle. The current elevation, 12,281 feet (3,743 m), is generated by the new method, NAVD88, for calculating altitudes.

Claude Ewing Rusk, a local settler and mountaineer, was one of those most familiar with Adams and he was instrumental in many of the names given to places around the mountain. In 1890, he, his mother Josie, and his sister Leah completed a circuit of the mountain and explored, to some extent, all ten of its principle glaciers. This was the first recorded circuit of Adams by a woman[59] and likely the first recorded circuit by anyone.[60] While they were on the east side, they named Avalanche Valley. Later, in 1897, after they had completed an ascent of Adams, they went to the Ridge of Wonders and his mother, awestruck by the scene, named it as such.[59]

No detailed descriptions of Adams or its glaciers existed until Professor William Denison Lyman and Horace S. Lyman published descriptions of three of its glaciers and various other features of the southern flanks of the mountain in 1886. The White Salmon/Avalanche, Mazama, and Klickitat Glaciers were those described. They also postulated Adams to be the source of some of the Columbia River basalt flows. They thought that Adams was within what was originally an enormous caldera that was about one hundred miles across. The southern boundary of this enormous caldera was the anticline ridge that forms the southern border of the Glenwood Valley.[37] Modern geology has since dismissed this theory. From information collected on an outing of the Mazamas in 1895, Professor Lyman expanded his descriptions of those three glaciers in 1896.[86] Adams was finally properly surveyed in 1901, when Rusk led noted geologist/glaciologist Harry Fielding Reid to Adams' remote location. Reid conducted the first systematic study of the volcano and also named its most significant glaciers, Pinnacle, Adams, Lava, Lyman, and Rusk with suggestions from Rusk.[59][60] He also named Castle Rock (The Castle), Little Mount Adams, and Red Butte.[28][59][87] Reid noted that it was apparent that the glaciers of Adams had been significantly larger during the Little Ice Age.[28][87] The geologic history of Adams would have to wait another 80 years before it was fully explored.[14]

On the 1895 Mazamas expedition, the first heliography between several of the peaks of the Cascades was attempted with some success. A party on Mount Hood was able to communicate back and forth with the party on Mount Adams, but the parties on Rainier, Baker, Jefferson, and Diamond Peak were not successful, mainly because of dense smoke and logistical problems.[59][83][88]

The first ascent of Mount Adams was in 1854 by Andrew Glenn Aiken,[89] Edward Jay Allen, and Andrew J. Burge.[80][82][90] While most sources list the aforementioned names, at least one substitutes Colonel Benjamin Franklin Shaw for Andrew Burge.[27] Their route was likely up the North Cleaver because that summer they were improving a newly designated military road that passes through Naches Pass, which is to the north of Adams.[82]

While the north and south faces of Adams are climbed easily, the west and east faces of the mountain were deemed impossible to climb because of the steep cliffs and ice cascades.[27] To some, this assumption was a challenge and for years, C. E. Rusk searched for a way to climb the east face. On one of these excursions, in 1919, Rusk named the Wilson Glacier, Victory Ridge, and the Roosevelt Cliff. It was on this trip that Rusk decided that the Castle held the easiest route up. In 1921, 67 years after the first ascent of Adams, a group from the Cascadians mountaineering club, led by Rusk, completed the first ascent of the precipitous east face of the mountain. Their route took them up the Rusk Glacier, onto Battlement Ridge, up and over The Castle, and across the vast, heavily crevassed eastern side of the summit ice cap.[59] One of the party, Edgar E. Coursen, said that the route was "thrilling to the point of extreme danger."[90] Others in the party were Wayne E. Richardson, Clarence Truitt, Rolland Whitmore, Robert E. Williams, and Clarence Starcher.[59][91] Three years later, in 1924, a group of three men from the Mazamas finally climbed the west face of Adams.[92] This route is straightforward, but made difficult by icefalls, mud slips, and easily started rock avalanches.[90]

Some of the caves around Adams were subject to commercial ventures. In the 1860s, ice was gathered from the Ice Cave and shipped to Portland and The Dalles in years of short supply elsewhere.[93] Oddly, a "claim" to the cave using mining laws was used in order to gain exclusive access to the ice.[39] Cheese Cave was used for potato storage in the 1930s and later was home to the Guler Cheese Company, which produced, for a number of years in the 1950s, a bleu cheese similar to the Roquefort produced in Roquefort-sur-Soulzon, France.[36][94][95] A legend from the Klickitats regarding the formation of the caves, involves a man and his wife who were of gigantic stature. The man left his wife and married a mouse, which became a woman. His wife was furious and because she threatened to kill the man and the "mouse-wife," they hid farther up the mountain at a lake. The man's wife assumed they were underground and began digging for them. In the process, she dug out the many caves in the area. Eventually, she reached the place where they were and the man allowed her to kill the "mouse-wife" to save his own life. Her blood colored the rocks of the lake red and the place was known as Hool-hool-se, which is from the Native American word for mouse. Eventually, the wife killed the man as well and lived alone in the mountains.[82]

Adams was the feature of a 1915 documentary When the Mountains Call. This film documented the journey from Portland to the summit and showed many of the sights along the way.[96]

Forest Service operations

[edit]

Adams and the lands surrounding it were initially set aside as part of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve under the Department of the Interior in 1897. Eight years later, in 1905, the Bureau of Forestry, later the Forest Service, was created under the Department of Agriculture and all the Forest Reserves were transferred to the new agency. In 1907, the Forest Reserves were renamed to National Forests and in 1908, the Rainier National Forest was divided among three Forests. The southern half became the Columbia National Forest. The name was changed in 1949 to honor the first Chief of the Forest, Gifford Pinchot. In 1964, the lands around Mount Adams were set aside as a wilderness.[97]

Adams is home to the oldest building on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, the Gotchen Creek Guard Station just south of the A. G. Aiken Lava Bed. Built in 1909, it served as the administrative headquarters of the Mount Adams District until 1916. It was built along a major grazing trail to allow for easy monitoring of the thousands of sheep grazed on the lower slopes. Later, in the 1940s, as the amount of grazing decreased, the station housed the Forest Guards responsible for the area.[98] It has been wrapped in protective foil as a precautionary method to shield it from a large wildfire.[98][99]

In 1916, the Forest Service began preparations to establish the highest fire lookout in the Pacific Northwest at the top of Adams. This was part of an endeavor that began in 1915 on Mount Hood[100] and 1916 on St. Helens[101] The idea was to situate lookouts far above all low-lying hills and mountains to give the lookouts an immense area for observation without obstructions. Being at 12,281 feet (3,743 m), the new lookout would also be the third highest in the world and still is.[102] In 1917, building materials were moved to the base of the mountain and in 1918, Dan Lewis packed the building materials and lumber to the lower portion of Suksdorf Ridge.[103][104] The following summer was spent hauling the building materials to the top.[103][104] The four men assigned the job, Arthur "Art" Jones, Adolph Schmid, Julius Wang, and Jessie Robbins, had a difficult task ahead of them until they engineered a way to quickly and, for the most part, safely bring the building materials up the slope using a deadman/rope technique.[104] Construction of the standard D-6 building with a ¼ second story cupola[105] began in the summer of 1920 and was completed a year later by Art, Adolph, James Huffman and Joe Guler.[59] It was manned as a lookout during the last year of its construction through 1924. After which it was abandoned because of the difficulties of operating a lookout that high and because lower level clouds, smoke, and haze frequently and effectively blocked the view of the lower elevations. Arthur Jones was likely the one person most involved in the project, spending five seasons on the mountain. Others who worked on the project or staffed the lookout include Rudolph Deitrich, the last lookout, and Chaffin "Chafe" Johnson.[104]

After the lookout at the summit was abandoned, the Forest Service changed strategies from a few lookouts very high up to many lookouts on lower peaks. They placed many lookouts around Adams including one on the southwest slopes of Adams at Madcat Meadows, one on Goat Butte, one on Council Bluff above Council Lake, and many other places farther from the mountain. Eventually these lookouts became obsolete as airplanes became the cheaper method to spot fires. Almost all of these lookouts have since been abandoned and most have been removed or left to disintegrate.[106][107] One, Burley Mountain, is staffed every summer[108] and another, Red Mountain, was restored in 2010 and decisions regarding its future are pending.[105][109] Two lookouts remain nearby on the Yakama Indian Reservation. One, Satus Peak, is staffed every season and the other, Signal Peak, is staffed during periods of high fire danger.[105]

Sulfur mine

[edit]In 1929, Wade Dean formed the Glacier Mining Company and filed mining claims to the sulfur on Adams' 210-acre (85.0 ha) summit plateau. Beginning in 1932, the first assessment work was done. The initial test pits were dug by hand, but this proved to be dangerous work and an alternative was needed to drill through the up to 210 feet (64 m) thick ice cap more safely. The answer was a diamond tipped drilling machine, but, being a heavy machine, it could not be carried up the newly completed horse and mule trail like other supplies. So it winched itself up the mountain using a series of deadman anchors. One hundred sixty-eight pack string trips led by John Perry were made over the course of the mining activities. The crew stayed in the abandoned Forest Service lookout, a tight fit for the usual eight men and their equipment. This problem was alleviated somewhat in the later years of the project when an enclosed 8 by 12 feet (2.4 by 3.7 m) lean-to was added to the cabin. Another smaller lean-to was added later. The conditions and weather above 12,000 feet (3,700 m) could be incredibly variable with the highest temperature of 110 °F (43 °C) recorded 12 hours before the lowest temperature of −48 °F (−44 °C). This preliminary mining continued for several years until 1937 when the last crew worked from the summit lookout. In the years following, Dean periodically attempted to restart this venture and in 1946, he and Lt. John Hodgkins made several landings by airplane on the summit ice cap. Although sulfur was found, the amount of the ore that was able to be mined in a season was only enough to make up the cost of getting it off the mountain and was not enough to be competitive. Part of this stemmed from Dean's desire that if operations were expanded, an ore as well as passenger transport system was needed, and his desire that Adams not be significantly scarred by the operation. The project was fully abandoned in 1959.[104] Adams is the only large Cascade volcano to have its summit exploited by commercial miners.[14][45]

Climate

[edit]

Because of its remote location and relative inaccessibility, climate records are poor. The nearest weather station, Potato Hill, has only been measuring precipitation since 1982 and temperatures since 1989.[110] Temperature and precipitation records from Glenwood and Trout Lake, both considerably lower in elevation and farther from the mountain, are more complete and go back further, 1948 at Glenwood[111] and 1924 at Trout Lake.[112] Snowfall records from the three snow stations on Adams cover a number of years but are discontinuous and are limited to the northwest side. The Potato Hill station was monitored monthly from 1950 to 1976 and was replaced in 1982 with the automated precipitation sensor. It was upgraded in 1983 to report snow water equivalent and it was upgraded again in 2006 to report snow depth.[110] The Council Pass station was monitored monthly from 1956 to 1978 and the Divide Meadow station was monitored monthly from 1962 to 1978. Divide Meadow was the most representative of the snow depth on the west side of Adams because it was the highest station on the flanks of the mountain.[113]

Like the rest of the high Cascade mountains, Adams receives a large amount of snow, but because it lies farther east than many of its Washington compatriots, it receives less than one might expect for a mountain of its height. Although snowfall is not measured directly, it can be estimated from the snow depth; and since the Potato Hill station was upgraded to report daily snow depth in 2006, there has been an average of 217 inches (550 cm) of snow every year. Also since 2006, the most snow to fall in a day was 33 inches (84 cm) (May 19, 2021), in a month, 92 inches (230 cm) (Dec 2007), and in a year, 288 inches (730 cm) (2012).[110]

By April, there is, on average, 87 inches (220 cm) of snow on the ground at Potato Hill.[110] The average monthly snow depth at Potato Hill has not changed much from the records collected from 1950 to 1976, with only a small decrease in January, February, and May and a small increase in March and April. Records from Council Pass and Divide Meadow also show depth increasing throughout the winter, peaking in April. These two stations average a greater amount of snow than Potato Hill, with an average of 102 inches (260 cm) at Council Pass and 141 inches (360 cm) at Divide Meadow by April. Divide Meadow generally receives the most snow, with a record depth of 222 inches (560 cm) in 1972. The snowpack at Potato Hill starts building in late October to early November and the last of the snow generally melts by the beginning of June, but occasionally lingers into July.[113]

Temperatures and precipitation can be highly variable around Adams, due in part to its geographic location astride the Cascade Crest, which gives it more of a continental influence than some of its neighbors. At Potato Hill, December is the coldest month with an average high of 45 °F (7 °C) and an average low of 6 °F (−14 °C). July is the hottest month with an average high of 84 °F (29 °C) and an average low of 33 °F (1 °C). The highest recorded temperature is 95 °F (35 °C) on June 29, 2021, and the lowest is −16 °F (−27 °C) on November 24, 2010. Average annual precipitation is 66.8 inches (1,700 mm) with January being the wettest month at 10.3 inches (26 cm), slightly more than November and December. Potato Hill averages 159 precipitation days with 53 snow days.[110] In Trout Lake, the coldest month is January with an average high of 36 °F (2 °C) and an average low of 22 °F (−6 °C). July is the hottest month with an average high of 83 °F (28 °C) and an average low of 48 °F (9 °C).[114] The highest recorded temperature is 108 °F (42 °C) in 1939 and the lowest is −26 °F (−32 °C) in 1930.[112] Average annual precipitation is 43.7 inches (1,110 mm) with January being the wettest month with 8.2 inches (210 mm).[114] In Glenwood, the coldest month is December with an average high of 37 °F (3 °C) and an average low of 23 °F (−5 °C). August is the hottest month with an average high of 81 °F (27 °C) and an average low of 42 °F (6 °C). The highest recorded temperature is 101 °F (38 °C) in 1994 and the lowest is −27 °F (−33 °C) in 1983. Average annual precipitation is 29.9 inches (760 mm) with December being the wettest month with 6 inches (150 mm).[115]

The climate of Adams places it and the immediate area in two different level three eco-regions: the Cascades eco-region and the Eastern Cascades Slopes and Foothills eco-region. Within these two eco-regions are five level four eco-regions: the Western Cascade Mountain Highlands, Cascade Crest Montane Forest, and Cascades Subalpine/Alpine within the Cascades eco-region and the Yakima Plateau and Slopes and Grand Fir Mixed Forest within the Eastern Cascades Slopes and Foothills eco-region. Adams is unique among the Washington volcanoes in that it is in two level three eco-regions as well as being the only one within the Cascade Crest Montane Forest.[116]

| Climate data for Mount Adams Summit. 1991-2020 (Modeled) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 17.4 (−8.1) |

16.6 (−8.6) |

17.7 (−7.9) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

37.3 (2.9) |

47.8 (8.8) |

48.1 (8.9) |

43.1 (6.2) |

33.0 (0.6) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 11.3 (−11.5) |

9.2 (−12.7) |

9.3 (−12.6) |

11.9 (−11.2) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

34.8 (1.6) |

35.1 (1.7) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

14.5 (−9.7) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 5.2 (−14.9) |

1.8 (−16.8) |

0.8 (−17.3) |

2.3 (−16.5) |

8.8 (−12.9) |

14.4 (−9.8) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

12.9 (−10.6) |

8.0 (−13.3) |

4.7 (−15.2) |

10.1 (−12.2) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 13.49 (343) |

10.28 (261) |

10.55 (268) |

6.89 (175) |

4.58 (116) |

3.11 (79) |

0.89 (23) |

1.21 (31) |

2.90 (74) |

7.66 (195) |

12.80 (325) |

14.36 (365) |

88.72 (2,253) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 4.1 (−15.5) |

0.2 (−17.7) |

−0.9 (−18.3) |

0.0 (−17.8) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

11.0 (−11.7) |

16.1 (−8.8) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

12.2 (−11.0) |

9.4 (−12.6) |

6.4 (−14.2) |

3.8 (−15.7) |

7.0 (−13.9) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[117] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

[edit]Flora

[edit]

The climate of Adams gives it a large amount of diversity within its forests. On the west side, down in the lower valleys, grand fir and Douglas fir dominate the forest with Western hemlock and Western red cedar as well. On the east side, Douglas fir and ponderosa pine are dominant with some patches of dense lodgepole pine. Western hemlock and Western red cedar also occur but are limited to creek and river bottoms. Grand fir is present on sites with better moisture retention. At middle elevations on the west side, grand fir is increasingly replaced by Pacific silver fir and noble fir; and on the east side, lodgepole becomes much more prevalent. Above a certain elevation, lodgepole pine also appears in areas on the west side as well. As elevation increases, the forest changes again with subalpine fir, Engelmann spruce, and mountain hemlock becoming the dominant tree species on all sides of the mountain. Eventually, the last trees to disappear from the mountainside are the highly cold tolerant whitebark pine and mountain hemlock. Other conifers, 18 species in all, that play a lesser role than the dominant species are Western white pine, Sitka spruce, Western larch, Pacific yew, Alaska cedar, and mountain juniper. Adams is also home to many hardwoods as well including the tree species big leaf maple, Oregon white oak, quaking aspen, black cottonwood, and red alder. Large shrubs/small trees include the dwarf birch, Suksdorf's hawthorn, California hazelnut, bitter cherry, vine maple, Douglas maple, and blue elderberry and contribute to a vibrant fall display.[116][118]

Big Tree, (also known as Trout Lake Big Tree), is a massive ponderosa pine tree in majestic, old growth pine and fir forests at the southern base of Mount Adams.[119] The tree rises to a lofty 202 feet (62 m)[120] with a diameter of 7 feet (2.1 m),[121] and is one of the largest known ponderosa pine trees in the world.[119] As of 2015, however, the tree has been stressed by attacks from pine beetles.[121]

The large diversity of the flora around Adams is even more apparent in the herbage and, including the tree and shrub species previously mentioned, totals at least 843 species. This is more than any other mountain in the Pacific Northwest. The first extensive list of flora from the area around Mount Adams was published in 1896 by William Suksdorf and Thomas Howell and listed 480 species. Suksdorf had taken it upon himself to catalogue as many species around Adams as he could and the list was the result of his extraordinary collection efforts.[122] This was the most complete list for over a century and has finally been updated by David Beik and Susan McDougall to the current 843 species with hundreds of additional species listed.[118] Adams is home to many rare plants including tall bugbane, Suksdorf's monkeyflower, northern microseris (Microceris borealis), Brewer's potentilla (Potentilla breweri), and mountain blue-eyed grass.[118] The plant diversity is most evident in the many meadows and wetlands on the flanks of Adams. The notable Bird Creek Meadows includes in its famous display, magenta paintbrush, arrowleaf ragwort, penstemons, lupines, monkeyflowers, mountain heathers, and many others. In wetlands, generally at lower elevations, one can find bog blueberry, highbush cranberry, sundew, purple cinquefoil, and flatleaf bladderwort, in addition to many sedges and rushes. Subalpine and alpine meadows and parklands, while not as prolific as the meadows and wetlands of lower elevations, have a display as well with partrigefoot, Cascade rockcress, subalpine buttercup, Sitka valerian, alpine false candytuft, elegant Jacob's ladder, and various buckwheats as prominent players.[116]

Fauna

[edit]

Adams is home to a fairly wide variety of animal species. Several hoofed mammals call the mountain home: mountain goats, Roosevelt elk, black-tailed deer, and mule deer. Large carnivores include cougar, black bear, coyote, bobcat, and the Cascade mountain fox,[123] an endemic subspecies of the red fox. There have also been sightings of wolverine[123][124] and unconfirmed reports of wolves.[125] Many small mammals also make Adams their home. Squirrels and chipmunks are numerous throughout the forest. Douglas squirrels, least chipmunks, and Townsend's chipmunks live throughout the forest with golden-mantled ground squirrels and California ground squirrels occupying drier areas as well. These squirrels are preyed upon by the elusive and secretive pine martens that also call Adams their home. Hoary marmots and pikas make their home on open rocky areas at any altitude while the elusive snowshoe hare lives throughout the forest.[116][123][126][127]

The profusion of wildflowers attracts a large number of pollinators including butterflies such as Apollos, Melitaea, Coenonympha, snowflakes, painted ladies, garden whites, swallowtails, skippers, admirals, sulphurs, blues, and fritillaries.[127][128]

Many birds call Adams home or a stopover on their migration routes. Songbirds include three species of chickadee, two kinglets, several thrushes, warblers, sparrows, and finches. One unique songbird to the high elevations is the gray-crowned rosy finch, who can be found far up the mountain, well above the tree line. Raptors that live in the forest and meadows include Accipiters, red-tailed hawks, golden and bald eagles, ospreys, great horned owls, and falcons. The many snags around the mountain provide forage and nesting habitat for the many species of woodpeckers that live there including the hairy woodpecker, downy woodpecker, and white-headed woodpecker. Jays such as the Steller's jay and Canada jay are common and the Canada jay is an especially familiar character, as they will boldly investigate campers and hikers. Another familiar character of the higher elevation forests is the Clark's nutcracker with its distinctive call. Swallows and swifts are frequently seen flying just above the water of lakes and some larger streams. Common mergansers and several other species of water birds can be found on many of the lakes as well. The American dipper with its unique way of bobbing about along streams and then ducking into the water is a common sight. Several grouse species, the sooty, spruce, and ruffed grouse and the white-tailed ptarmigan, call the forests and the lower slopes of the mountain home.[116][127][129]

The streams and lakes around Adams offer a number of fish for the angler to seek out. The two most common species, eastern brook trout and rainbow trout (Columbia River redband trout), are in nearly every lake and stream. Brown trout and cutthroat trout appear in most of the lakes in the High Lakes Area and three lakes are home to tiger trout. All the lakes in the High Lakes Area are periodically replanted with varying species of trout.[130] Bull trout can be found in the upper reaches of the Klickitat and Lewis Rivers.[131][132] Westslope cutthroat trout can be found the Klickitat and cutthroat trout are found in the Lewis River and upper reaches of the Cispus River. Whitefish can be found in the Klickitat, Lewis, and Cispus Rivers.[131][132] Because of barriers to fish passage (dams on the Lewis and Cowlitz Rivers, falls on the White Salmon River), the only river where anadromous fishes can reach the streams around Adams is the Klickitat River. Chinook salmon, coho salmon, and steelhead, in several different runs, make for the upper reaches of the Klickitat, including those around Adams, every year.[132]

The Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge lies at the base of Mount Adams. The refuge covers 6,500 acres (2,600 ha) and contains conifer forests, grasslands, and shallow wetlands. Protected wildlife includes deer, elk, beaver, coyote, otter, small rodents, bald eagle, greater sandhill crane, and the Oregon spotted frog.[133] It and the lands nearby are home to several rare and threatened species of plants and animals including the previously mentioned Oregon spotted frog and greater sandhill crane, Suksdorf's milk vetch, rosy owl's-clover, Oregon coyote thistle, Mardon skipper, peregrine falcon, and Western gray squirrel.[134]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Mount Adams". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ a b "Mount Adams, Washington". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ "Adams". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- ^ USGS Volcanoes (February 14–15, 2019). "Mount Adams, also known by the Native [...]". U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.5066/P9Z1HF1K – via Facebook.

Mount Adams, also known by the Native American names "Klickitat" or "Pahto" [...]

- ^ a b Wright, T.L.; Pierson, T.C. (1992). Living With Volcanoes. The U.S. Geological Survey's Volcano Hazards Program: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1073 (Report). USGS. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ "Washington's 100 highest Mountains". Cascade Alpine Guide. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ a b c d Scott, W.E.; Iverson, R.M.; Vallance, J.W.; Hildreth, W. (1995). Volcano Hazards in the Mount Adams Region, Washington. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 95-492 (Report). USGS. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (1990). Volcanoes of North America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

- ^ a b c d e "Mt. Adams Wilderness". Gifford Pinchot National Forest. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Official Site of the Yakama Nation". Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ "Pacific Northwest Region Viewing Area - Mt. Adams Wilderness, Pacific Crest Trail, Adams Creek". Celebrating Wildflowers. USFS. 2008-06-24. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ^ "Washington Segment". Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail Website. USFS. Retrieved 2008-08-06.

- ^ a b c "Description: Mount Adams Volcano, Washington". Cascades Volcano Observatory. USGS. Retrieved 2008-12-21.