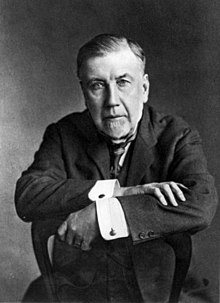

John Ross Robertson

John Ross Robertson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Canadian Parliament for Toronto East | |

| In office 1896–1900 | |

| Preceded by | Emerson Coatsworth |

| Succeeded by | Albert Edward Kemp |

| Personal details | |

| Born | December 28, 1841 Toronto, Canada West |

| Died | May 31, 1918 (aged 76) Toronto, Ontario |

| Political party | Independent Conservative |

John Ross Robertson (December 28, 1841 – May 31, 1918) was a Canadian newspaper publisher, politician, and philanthropist in Toronto, Ontario.

Career

[edit]Born in 1841, in Toronto, the son of John Robertson, a Scottish wholesale merchant, and Margaret Sinclair, Robertson was educated at Upper Canada College, a private high school in Toronto.[1] As a young man, he started a newspaper at UCC called Young Canada and a satirical weekly magazine, The Grumbler. The Grumbler was published in 1864 in a building on the corner of King Street and Toronto Street in Toronto. The Grumbler was one of Robertson's more well known publications.

He was hired as a reporter and then city editor at The Globe in Toronto, but left The Globe to found The Toronto Daily Telegraph in 1866. That paper lasted five years,[2] and Robertson went to England as a reporter for The Globe.[1] He returned to Toronto in 1876 and convinced his friend and former colleague, Goldwin Smith, to loan him $10,000 to enable him to launch the Toronto Evening Telegram.[3] In the Toronto Evening Telegram he wrote a recurring column on Toronto landmarks. The Evening Telegram was a success from the start and Robertson was soon a wealthy man. Eventually these columns were published in a book called Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto which consists of six volumes.[4]

He was elected to the House of Commons of Canada for the electoral district of Toronto East in the 1896 federal election defeating the incumbent Conservative MP, Emerson Coatsworth. An Independent Conservative, he did not run for re-election in 1900.[citation needed]

The world of sports was also a focus for Robertson’s public-spiritedness. A fervent advocate of amateur sport, he served as president of the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA) from 1899 to 1905, which was a critical time period in the history of the sport.[1] His battle to protect hockey from the influence of professionalism caused him to be called the "father of Amateur Hockey in Ontario."[5] During his term as president, the OHA was able to set rules defining professionalism in hockey. He worked especially hard to rid hockey of increasing violence both on and off the ice.[6] Robertson donated three similarly named trophies to the OHA for its annual playoffs champions, which included the first J. Ross Robertson Cup for the senior division, the second J. Ross Robertson Cup for the intermediate division, and the third J. Ross Robertson Cup for the junior division.[7][8] His donation of silver trophies to hockey, cricket, and bowling further encouraged amateur competition.[citation needed] He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947.[9]

Robertson was also one of Toronto's great historians and his home was filled with thousands of books and pictures of early Toronto. In his will, Mr. Robertson left to the citizens of Toronto his extensive collection of historical maps and paintings. He also helped fund The Hospital for Sick Children.[citation needed]

In 1881, Robertson’s daughter Helen and niece Gracie died of scarlet fever on the same day.[10] As a result, his wife Maria Robertson and his wife were profoundly affected by the death of Goldie and as soon as Mrs. Robertson recovered from her grief she began working as a volunteer at a new hospital which had been started by Elizabeth McMaster and a group of ladies.[citation needed] One day, Maria persuaded her husband to visit the hospital. Robertson was appalled at what he saw. Because the hospital had little money, the children were sleeping on torn mattresses in rooms so dilapidated they couldn't be scrubbed clean. The next day, Robertson sent a cartload of beds and bedding and began a new career that would dominate the rest of his life.[citation needed]

In 1883, Robertson, at his own expense, build The Lakeside Home for Little Children, on Toronto Island.[11] The Lakeside Home was a convalescent hospital usually occupied from June 1 to September 30.[citation needed] The Lakeside Home was demolished in a fire in 1915 and temporary buildings were used until 1928. In 1921, John Ross Robertson Public School donated $100 to Lakeside Home to maintain a cot. It was common practice for schools to donate money to maintain the cots on an annual basis.[citation needed]

Realizing the desperate need for a larger hospital for children in the city, Robertson embarked on an extensive tour of children's hospitals in Europe and the United States. He wanted the hospital for sick children in Toronto to become one of the finest institutions of its kind in the world. Finally, Mr. Robertson saw his ideal - the recently opened hospital for sick children in Glasgow, Scotland. He asked the Scottish architect who had drawn up the plans of the hospital to draft blueprints for the proposed hospital in Toronto and placed these plans in the hands of Toronto Architects Darling and Curry. The new building became a reality and on June 10, 1889, Mr. Robertson's seven-year-old son turned over the first sod. The building was on College Street between LaPlante Avenue and Elizabeth Street.[citation needed]

Robertson raised money for the new hospital through publicity in his newspaper by gaining support of influential citizens in the city and with the aid of a $20,000 grant from Toronto Council.[citation needed]

When Robertson first heard of pasteurized milk in the early 1900s, he sent his sister off to New York City to learn the new process. The hospital was provided with a fully equipped plant to provide pasteurized milk for the babies in the in and outpatient departments with the goal of reducing the infantile death rate. If the families were unable to afford the milk, it would be provided for them. To make sure the bottles would be returned and not kept for flower vases or any other purposes, they made rounded bottom bottles, which could not stand, on a flat surface.[citation needed]

In 1902, Robertson was appointed Grand Junior Warden of England.[12] He also became president of the inaugural Canadian Copyright Association.[13] A few years later, he refused Knighthood honour and chose to remain a companion.[14]

Robertson became Chairman of the Hospital in 1891 and remained Chairman until he died in 1918. In 1951, the hospital moved to its present building on University Avenue.

He bequeathed his considerable book collection to the Toronto Public Library, founded a children's home, and left a large annuity to the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children. The John Ross Robertson Public School, an elementary school of the Toronto District School Board is named after Robertson, and is located at 130 Glengrove Avenue West in Toronto.[citation needed]. Construction of the school started shortly after his death.

References

[edit]General

- "John Ross Robertson". Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. 1979–2016.

- John Ross Robertson – Parliament of Canada biography

Specific

- ^ a b c "John Ross Robertson". Brandon Daily Sun. Manitoba. May 5, 1955.

- ^ Hopkins, J. Castell (1898). An historical sketch of Canadian literature and journalism. Toronto: Lincott. p. 227. ISBN 0665080484.

- ^ Dickie, Allan (October 30, 1971). "Tely officially dead today". Brandon Sun. Manitoba.

- ^ Peppiatt, Liam. "About". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Archived from the original on September 14, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

- ^ "John Ross Robertson". heritagetrust.on.ca. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Young, Scott (1989). 100 Years of Dropping the Puck. Toronto, Ontario: McClelland & Stewart. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-7710-9093-5.

- ^ "Robertson, John Ross—Biography—Honoured Builder". Legends of Hockey. Hockey Hall of Fame. 1947. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Podnieks, Andrew; Hockey Hall of Fame (2005). Silverware. Bolton, Ontario: Fenn Publishing Company. pp. 8–9. ISBN 1-55168-296-6.

- ^ "John Ross Robertson". hhof.com. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Wright, David (January 6, 2017). SickKids: The History of The Hospital for Sick Children. University of Toronto Press. pp. 50–57. ISBN 9781442667570. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ Young, Judith (1994). "A Divine Mission: Elizabeth McMaster and the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 11 (1): 73–81. doi:10.3138/cbmh.11.1.71. PMID 11639375.

- ^ "Honors for Canadian Mason". Winnipeg Free Press. Manitoba. July 29, 1902.

- ^ "Copyright Association". Winnipeg Tribune. Manitoba. July 8, 1902.

- ^ "The Progress of War". Lethbridge Herald. Alberta. February 20, 1917. p. 4.

External links

[edit]- Biographical information and career statistics from Legends of Hockey

- Works by John Ross Robertson at Faded Page (Canada)

- John Ross Robertson Public School

- 1841 births

- 1918 deaths

- 19th-century Canadian newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th-century Canadian philanthropists

- 20th-century Canadian philanthropists

- 19th-century members of the House of Commons of Canada

- Burials at Toronto Necropolis

- Canadian journalists

- Canadian newspaper founders

- Canadian sportsperson-politicians

- Hockey Hall of Fame inductees

- Independent Conservative MPs in the Canadian House of Commons

- Journalists from Toronto

- Members of the House of Commons of Canada from Ontario

- Ontario Hockey Association executives

- Politicians from Toronto

- Pre-Confederation Ontario people

- Upper Canada College alumni