Movie theater

A movie theater (American English),[1] cinema (British English),[2] or cinema hall (Indian English),[3] also known as a movie house, picture house, picture theater or simply theater, is a business that contains auditoria for viewing films for public entertainment. Most are commercial operations catering to the general public, who attend by purchasing tickets.

The film is projected with a movie projector onto a large projection screen at the front of the auditorium while the dialogue, sounds and music are played through a number of wall-mounted speakers. Since the 1970s, subwoofers have been used for low-pitched sounds. Since the 2010s, the majority of movie theaters have been equipped for digital cinema projection, removing the need to create and transport a physical film print on a heavy reel.

A great variety of films are shown at cinemas, ranging from animated films to blockbusters to documentaries. The smallest movie theaters have a single viewing room with a single screen. In the 2010s, most movie theaters had multiple screens. The largest theater complexes, which are called multiplexes—a concept developed in Canada in the 1950s—have up to thirty screens. The audience members often sit on padded seats, which in most theaters are set on a sloped floor, with the highest part at the rear of the theater. Movie theaters often sell soft drinks, popcorn and candy, and some theaters sell hot fast food. In some jurisdictions, movie theaters can be licensed to sell alcoholic drinks.

Terminology

[edit]

A movie theater might also be referred to as a movie house, film house, film theater, cinema or picture house. In the US, theater has long been the preferred spelling, while in the UK, Australia, Canada and elsewhere it is theatre.[4]

However, some US theaters opt to use the British spelling in their own names, a practice supported by the National Association of Theatre Owners, while apart from Anglophone North America most English-speaking countries use the term cinema /ˈsɪnɪmə/, alternatively spelled and pronounced kinema /ˈkɪnɪmə/.[5][6][7] The latter terms, as well as their derivative adjectives "cinematic" and "kinematic", ultimately derive from Greek κίνημα, κινήματος (kinema, kinematos)—"movement, motion". In the countries where those terms are used, the word "theatre" is usually reserved for live performance venues.

Colloquial expressions, mostly applied to motion pictures and motion picture theaters collectively, include the silver screen (formerly sometimes sheet) and the big screen (contrasted with the smaller screen of a television set). Specific to North American term is the movies, while specific terms in the UK are the pictures, the flicks and for the facility itself the flea pit (or fleapit). A screening room is a small theater, often a private one, such as for the use of those involved in the production of motion pictures or in a large private residence.

The etymology of the term "movie theater" involves the term "movie", which is a "shortened form of moving picture in the cinematographic sense" that was first used in 1896[8] and "theater", which originated in the "...late 14c., [meaning an] open air place in ancient times for viewing spectacles and plays". The term "theater" comes from the Old French word "theatre", from the 12th century and "...directly from Latin theatrum [which meant] 'play-house, theater; stage; spectators in a theater'", which in turn came from the Greek word "theatron", which meant "theater; the people in the theater; a show, a spectacle", [or] literally "place for viewing". The use of the word "theatre" to mean a "building where plays are shown" dates from the 1570s in the English language.[9]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]Movie theatres stand in a long tradition of theaters that could house all kinds of entertainment. Some forms of theatrical entertainment would involve the screening of moving images and can be regarded as precursors of film.

In 1799, Étienne-Gaspard "Robertson" Robert moved his Phantasmagorie show to an abandoned cloister near the Place Vendôme in Paris. The eerie surroundings, with a graveyard and ruins, formed an ideal location for his ghostraising spectacle.

When it opened in 1838, The Royal Polytechnic Institution in London became a very popular and influential venue with all kinds of magic lantern shows as an important part of its program. At the main theatre, with 500 seats, lanternists would make good use of a battery of six large lanterns running on tracked tables to project the finely detailed images of extra large slides on the 648 square feet screen. The magic lantern was used to illustrate lectures, concerts, pantomimes and other forms of theatre. Popular magic lantern presentations included phantasmagoria, mechanical slides, Henry Langdon Childe's dissolving views and his chromatrope.[10][11]

The earliest known public screening of projected stroboscopic animation was presented by Austrian magician Ludwig Döbler on 15 January 1847 at the Josephstadt Theatre in Vienna, with his patented Phantaskop. The animated spectacle was part of a well-received show that sold out in several European cities during a tour that lasted until the spring of 1848.[12][13][14][15]

The famous Parisian entertainment venue Le Chat Noir opened in 1881 and is remembered for its shadow plays, renewing the popularity of such shows in France.

Earliest motion picture screening venues

[edit]The earliest public film screenings took place in existing (vaudeville) theatres and other venues that could be darkened and comfortably house an audience.

Émile Reynaud screened his Pantomimes Lumineuses animated movies from 28 October 1892 to March 1900 at the Musée Grévin in Paris, with his Théâtre Optique system. He gave over 12,800 shows to a total of over 500,000 visitors, with programs including Pauvre Pierrot and Autour d'une cabine.[16][17]

Thomas Edison initially believed film screening would not be as viable commercially as presenting films in peep boxes, hence the film apparatus that his company would first exploit became the kinetoscope. A few public demonstrations occurred since 9 May 1893, before a first public Kinetoscope parlor was opened on 14 April 1894, by the Holland Bros. in New York City at 1155 Broadway, on the corner of 27th Street. This can be regarded as the first commercial motion picture house. The venue had ten machines, set up in parallel rows of five, each showing a different movie. For 25 cents a viewer could see all the films in either row; half a dollar gave access to the entire bill.[18]

The Eidoloscope, devised by Eugene Augustin Lauste for the Latham family, was demonstrated for members of the press on 21 April 1895 and opened to the paying public on 20 May, in a lower Broadway store with films of the Griffo-Barnett prize boxing fight, taken from Madison Square Garden's roof on 4 May.[19]

Max Skladanowsky and his brother Emil demonstrated their motion pictures with the Bioscop in July 1895 at the Gasthaus Sello in Pankow (Berlin). This venue was later, at least since 1918, exploited as the full-time movie theatre Pankower Lichtspiele and between 1925 and 1994 as Tivoli.[20] The first certain commercial screenings by the Skladanowsky brothers took place at the Wintergarten in Berlin from 1 to 31 November 1895.[21]

The first commercial, public screening of films made with Louis and Auguste Lumière's Cinématographe took place in the basement of Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris on 28 December 1895.

Early dedicated movie theatres

[edit]

During the first decade of motion pictures, the demand for movies, the amount of new productions, and the average runtime of movies, kept increasing, and at some stage it was viable to have theaters that would no longer program live acts, but only movies.

The first building built for the dedicated purpose of showing motion pictures was built to demonstrate The Phantoscope, a device created by Jenkins & Armat, as part of The Cotton State Exposition on September 25, 1895 in Atlanta, GA. This is arguably the first cinema in the world.

Claimants for the title of the earliest movie theatre include the Eden Theater in La Ciotat, where L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat was screened on 21 March 1899. The theatre closed in 1995 but re-opened in 2013.[22]

L'Idéal Cinéma in Aniche (France), built in 1901 as l'Hôtel du Syndicat CGT, showed its first film on 23 November 1905. The cinema was closed in 1977 and the building was demolished in 1993. The "Centre Culturel Claude Berri" was built in 1995; it integrates a new movie theater (the Idéal Cinéma Jacques Tati).[23][24]

In the United States, many small and simple theaters were set up, usually in converted storefronts. They typically charged five cents for admission, and thus became known as nickelodeons. This type of theatre flourished from about 1905 to circa 1915.[citation needed]

The Korsør Biograf Teater, in Korsør, Denmark, opened in August 1908 and is the oldest known movie theater still in continuous operation.[25]

-

A small still-active Kino Juha movie theatre in Nurmijärvi, Finland, opened in 1958

-

Regent Theatre in Hokitika, New Zealand

Design

[edit]

Traditionally a movie theater, like a stage theater, consists of a single auditorium with rows of comfortable padded seats, as well as a foyer area containing a box office for buying tickets. Movie theaters also often have a concession stand for buying snacks and drinks within the theater's lobby. Other features included are film posters, arcade games and washrooms. Stage theaters are sometimes converted into movie theaters by placing a screen in front of the stage and adding a projector; this conversion may be permanent, or temporary for purposes such as showing arthouse fare to an audience accustomed to plays. The familiar characteristics of relatively low admission and open seating can be traced to Samuel Roxy Rothafel, an early movie theater impresario. Many of these early theaters contain a balcony, an elevated level across the auditorium above the theater's rearmost seats. The rearward main floor "loge" seats were sometimes larger, softer, and more widely spaced and sold for a higher price. In conventional low pitch viewing floors, the preferred seating arrangement is to use staggered rows. While a less efficient use of floor space this allows a somewhat improved sight line between the patrons seated in the next row toward the screen, provided they do not lean toward one another.

"Stadium seating", popular in modern multiplexes, actually dates back to the 1920s. The 1922 Princess Theatre in Honolulu, Hawaii featured "stadium seating", sharply raked rows of seats extending from in front of the screen back towards the ceiling. It gives patrons a clear sight line over the heads of those seated in front of them. Modern "stadium seating" was utilized in IMAX theaters, which have very tall screens, beginning in the early 1970s.

Rows of seats are divided by one or more aisles so that there are seldom more than 20 seats in a row. This allows easier access to seating, as the space between rows is very narrow. Depending on the angle of rake of the seats, the aisles have steps. In older theaters, aisle lights were often built into the end seats of each row to help patrons find their way in the dark. Since the advent of stadium theaters with stepped aisles, each step in the aisles may be outlined with small lights to prevent patrons from tripping in the darkened theater. In movie theaters, the auditorium may also have lights that go to a low level, when the movie is going to begin. Theaters often have booster seats for children and other people of short stature to place on the seats to allow them to sit higher, for a better view. Many modern theaters have accessible seating areas for patrons in wheelchairs. See also luxury screens below.

-

Cinema Odeon auditorium in Florence

-

Interior of Hoyts cinemas auditorium in Perth, Australia, with stadium seating with cup holders, acoustic wall hangings and wall-mounted speakers.

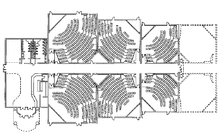

Multiplexes and megaplexes

[edit]

Canada was the first country in the world to have a two-screen theater. The Elgin Theatre in Ottawa, Ontario became the first venue to offer two film programs on different screens in 1957 when Canadian theater-owner Nat Taylor converted the dual screen theater into one capable of showing two different movies simultaneously. Taylor is credited by Canadian sources as the inventor of the multiplex or cineplex; he later founded the Cineplex Odeon Corporation, opening the 18-screen Toronto Eaton Centre Cineplex, the world's largest at the time, in Toronto, Ontario.[26] In the United States, Stanley Durwood of American Multi-Cinema (now AMC Theatres) is credited as pioneering the multiplex in 1963 after realizing that he could operate several attached auditoriums with the same staff needed for one through careful management of the start times for each movie. Ward Parkway Center in Kansas City, Missouri had the first multiplex cinema in the United States.

Since the 1960s, multiple-screen theaters have become the norm, and many existing venues have been retrofitted so that they have multiple auditoriums. A single foyer area is shared among them. In the 1970s, many large 1920s movie palaces were converted into multiple screen venues by dividing their large auditoriums, and sometimes even the stage space, into smaller theaters. Because of their size, and amenities like plush seating and extensive food/beverage service, multiplexes and megaplexes draw from a larger geographic area than smaller theaters. As a rule of thumb, they pull audiences from an eight to 12-mile radius, versus a three to five-mile radius for smaller theaters (though the size of this radius depends on population density).[27] As a result, the customer geography area of multiplexes and megaplexes typically overlaps with smaller theaters, which face threat of having their audience siphoned by bigger theaters that cut a wider swath in the movie-going landscape.

In most markets, nearly all single-screen theaters (sometimes referred to as a "Uniplex") have gone out of business; the ones remaining are generally used for arthouse films, e.g. the Crest Theatre[28] in downtown Sacramento, California, small-scale productions, film festivals or other presentations. Because of the late development of multiplexes, the term "cinema" or "theater" may refer either to the whole complex or a single auditorium, and sometimes "screen" is used to refer to an auditorium. A popular film may be shown on multiple screens at the same multiplex, which reduces the choice of other films but offers more choice of viewing times or a greater number of seats to accommodate patrons. Two or three screens may be created by dividing up an existing cinema (as Durwood did with his Roxy in 1964), but newly built multiplexes usually have at least six to eight screens, and often as many as twelve, fourteen, sixteen or even eighteen.

Although definitions vary, a large multiplex with 20 or more screens is usually called a "megaplex". However, in the United Kingdom, this was a brand name for Virgin Cinema (later UGC). The first megaplex is generally considered to be the Kinepolis in Brussels, Belgium, which opened in 1988 with 25 screens and a seating capacity of 7,500. The first theater in the U.S. built from the ground up as a megaplex was the AMC Grand 24 in Dallas, Texas, which opened in May 1995, while the first megaplex in the U.S.-based on an expansion of an existing facility was Studio 28 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which reopened in November 1988 with 20 screens and a seating capacity of 6,000.

Drive-in

[edit]

A drive-in movie theater is an outdoor parking area with a screen—sometimes an inflatable screen—at one end and a projection booth at the other. Moviegoers drive into the parking spaces which are sometimes sloped upwards at the front to give a more direct view of the movie screen. Movies are usually viewed through the car windscreen (windshield) although some people prefer to sit on the bonnet (hood) of the car. Some may also sit in the trunk (back) of their car if space permits. Sound is either provided through portable loudspeakers located by each parking space, or is broadcast on an FM radio frequency, to be played through the car's stereo system. Because of their outdoor nature, drive-ins usually only operate seasonally, and after sunset. Drive-in movie theaters are mainly found in the United States, [citation needed] where they were especially popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Once numbering in the thousands, about 400 remain in the U.S. today. In some cases, multiplex or megaplex theaters were built on the sites of former drive-in theaters.

Other venues

[edit]

Some outdoor movie theaters are just grassy areas where the audience sits upon chairs, blankets or even in hot tubs, and watch the movie on a temporary screen, or even the wall of a building. Colleges and universities have often sponsored movie screenings in lecture halls. The formats of these screenings include 35 mm, 16 mm, DVD, VHS, and even 70 mm in rare cases. Some alternative methods of showing movies have been popular in the past. In the 1980s the introduction of VHS cassettes made possible video-salons, small rooms where visitors viewed movies on a large TV. These establishments were especially popular in the Soviet Union, where official distribution companies were slow to adapt to changing demand, and so movie theaters could not show popular Hollywood and Asian films.

In 1967, the British government launched seven custom-built mobile cinema units for use as part of the Ministry of Technology campaign to raise standards. Using a very futuristic look, these 27-seat cinema vehicles were designed to attract attention. They were built on a Bedford SB3 chassis with a custom Coventry Steel Caravan extruded aluminum body. Movies are also commonly shown on airliners in flight, using large screens in each cabin or smaller screens for each group of rows or each individual seat; the airline company sometimes charges a fee for the headphones needed to hear the movie's sound. In a similar fashion, movies are sometimes also shown on trains, such as the Auto Train.

The smallest purpose-built cinema is the Cabiria Cine-Cafe which measures 24 m2 (260 sq ft) and has a seating capacity of 18. It was built by Renata Carneiro Agostinho da Silva (Brazil) in Brasília DF, Brazil in 2008. It is mentioned in the 2010 Guinness World Records. The World's smallest solar-powered mobile cinema is Sol Cinema in the UK. Touring since 2010 the cinema is actually a converted 1972 caravan. It seats 8–10 at a time. In 2015 it featured in a Lenovo advert for the launch of a new tablet. The Bell Museum of Natural History in Minneapolis, Minnesota has recently begun summer "bike-ins", inviting only pedestrians or people on bicycles onto the grounds for both live music and movies. In various Canadian cities, including Toronto, Calgary, Ottawa and Halifax, al-fresco movies projected on the walls of buildings or temporarily erected screens in parks operate during the Summer and cater to a pedestrian audience. The New Parkway Museum in Oakland, California replaces general seating with couches and coffee tables, as well as having a full restaurant menu instead of general movie theater concessions such as popcorn or candy.[citation needed]

In certain countries, there are also Bed Cinemas where the audience sits or lays in beds instead of chairs.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]

3D

[edit]

3D film is a system of presenting film images so that they appear to the viewer to be three-dimensional. Visitors usually borrow or keep special glasses to wear while watching the movie. Depending on the system used, these are typically polarized glasses. Three-dimensional movies use two images channeled, respectively, to the right and left eyes to simulate depth by using 3D glasses with red and blue lenses (anaglyph), polarized (linear and circular), and other techniques. 3D glasses deliver the proper image to the proper eye and make the image appear to "pop-out" at the viewer and even follow the viewer when he/she moves so viewers relatively see the same image.

The earliest 3D movies were presented in the 1920s. There have been several prior "waves" of 3D movie distribution, most notably in the 1950s when they were promoted as a way to offer audiences something that they could not see at home on television. Still the process faded quickly and as yet has never been more than a periodic novelty in movie presentation. The "golden era" of 3D film began in the early 1950s with the release of the first color stereoscopic feature, Bwana Devil.[38] The film starred Robert Stack, Barbara Britton and Nigel Bruce. James Mage was an early pioneer in the 3D craze. Using his 16 mm 3D Bolex system, he premiered his Triorama program in February 1953 with his four shorts: Sunday In Stereo, Indian Summer, American Life, and This is Bolex Stereo.[39] 1953 saw two groundbreaking features in 3D: Columbia's Man in the Dark and Warner Bros. House of Wax, the first 3D feature with stereophonic sound. For many years, most 3D movies were shown in amusement parks and even "4D" techniques have been used when certain effects such as spraying of water, movement of seats, and other effects are used to simulate actions seen on the screen. The first decline in the theatrical 3D craze started in August and September 1953.

In 2009, movie exhibitors became more interested in 3D film. The number of 3D screens in theaters is increasing. The RealD company expects 15,000 screens worldwide in 2010. The availability of 3D movies encourages exhibitors to adopt digital cinema and provides a way for theaters to compete with home theaters. One incentive for theaters to show 3D films is that although ticket sales have declined, revenues from 3D tickets have grown.[40] In the 2010s, 3D films became popular again. The IMAX 3D system and digital 3D systems are used (the latter is used in the animated movies of Disney/Pixar). The RealD 3D system works by using a single digital projector that swaps back and forth between the images for eyes. A filter is placed in front of the projector that changes the polarization of the light coming from the projector. A silver screen is used to reflect this light back at the audience and reduce loss of brightness. There are four other systems available: Volfoni, Master Image, XpanD and Dolby 3D.

When a system is used that requires inexpensive 3D glasses, they can sometimes be kept by the patron. Most theaters have a fixed cost for 3D, while others charge for the glasses, but the latter is uncommon (at least in the United States). For example, in Pathé theaters in the Netherlands the extra fee for watching a 3D film consists of a fixed fee of €1.50, and an optional fee of €1 for the glasses.[41] Holders of the Pathé Unlimited Gold pass (see also below) are supposed to bring along their own glasses; one pair, supplied yearly, more robust than the regular type, is included in the price.

IMAX

[edit]IMAX is a system using 70 mm film with more than ten times the frame size of a 35 mm film. IMAX theaters use an oversized screen as well as special projectors. The first permanent IMAX theater was at Ontario Place in Toronto, Canada. Until 2016, visitors to the IMAX cinema attached to the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, West Yorkshire, England, United Kingdom, could observe the IMAX projection booth via a glass rear wall and watch the large format films being loaded and projected.[42] The largest permanent IMAX cinema screen measures 38.80 m × 21.00 m (127.30 ft × 68.90 ft) and was achieved by Traumplast Leonberg (Germany) in Leonberg, Germany, verified on 6 December 2022.[43][44]

IMAX also refers to a digital cinema format that uses dual 2K resolution projectors and a screen with a 1.90:1 aspect ratio; this system is designed primarily for use in retrofitted multiplexes, using screens significantly smaller than those normally associated with IMAX.[45] In 2015, IMAX introduced an updated "IMAX with Laser" format, using 4K resolution laser projectors.[46]

The term "premium large format" (PLF) emerged in the mid-2010s to refer to auditoriums with high-end amenities. PLF does not refer to a single format in general, but combinations of non-proprietary amenities such as larger "wall-to-wall" screens, 4K projectors, 7.1 and/or positional surround sound systems (including Dolby Atmos), and higher-quality seating (such as leather recliners). Cinemas typically brand PLF auditoriums with chain-specific trademarks, such as "Prime" (AMC), "BTX" (Bow Tie),[47] "Superscreen" (Cineworld), "BigD" (Carmike, now owned by AMC), "UltraAVX" (Cineplex), "Macro XE" (Cinépolis), "XD" (Cinemark), "BigPix" (INOX),[48] "Laser Ultra" (Kinepolis and Landmark Cinemas), "RPX" (Regal Cinemas), "Superscreen DLX"/"Ultrascreen DLX" (Marcus),[49] "Titan" (Reading Cinemas),[50][51][52] "VueXtreme" (Vue International), and "X-land" (Wanda Cinemas).[53][54][55]

PLFs compete primarily with formats such as digital IMAX; the use of common "off-the-shelf" components and an in-house brand removes the need to pay licensing fees to a third-party for a proprietary large format.[53][54] Although the term is synonymous with exhibitor-specific brands, some PLFs are franchised. Dolby franchises Dolby Cinema, which is based on technologies such as Atmos and Dolby Vision.[56][54] CJ CGV franchises the 4DX and ScreenX formats.[57]

Motion controlled seating

[edit]In some theaters, seating can be dynamically moved via haptic motion technology called D-BOX.

In digital cinema, D-BOX codes for motion control are stored in the Digital Cinema Package for the film. Control data is encoded in a monoaural WAV file on Sound Track channel 13, labelled as "Motion Data".[58] Motion Data tracks are unencrypted and not watermarked.[59]

Programming

[edit]

Movie theaters may be classified by the type of movies they show or when in a film's release process they are shown:

- First-run theater: A theater that runs primarily mainstream film fare from the major film companies and distributors, during the initial new release period of each film.

- Second-run or discount theater: A theater that runs films that have already shown in the first-run theaters and presented at a lower ticket price. (These are sometimes known as dollar theaters or "cheap seats".) This form of cinema is diminishing in viability owing to the increasingly shortened intervals before the films' home video release, called the "video window".

- Repertoire/repertory theater or arthouse: A theater that presents more alternative and art films as well as second-run and classic films (often known as an "independent cinema" in the UK).

- An adult movie theater or sex theater specializes in showing pornographic movies. Such movies are rarely shown in other theaters. See also Golden Age of Porn. Since the widespread availability of pornographic films for home viewing on VHS in the 1980s and 1990s, the DVD in the 1990s, and the Blu-ray disc in the 2000s, there are far fewer adult movie theaters.

- IMAX theaters can show conventional movies, but the major benefits of the IMAX system are only available when showing movies filmed using it. While a few mainstream feature films have been produced in IMAX, IMAX movies are often documentaries featuring natural scenery, and may be limited to the 45-minute length of a single reel of IMAX film.

Presentation

[edit]

Usually in the 2020s, an admission is for one feature film. Sometimes two feature films are sold as one admission (double feature), with a break in between. Separate admission for a short subject is rare; it is either an extra before a feature film or part of a series of short films sold as one admission (this mainly occurs at film festivals). (See also anthology film.) In the early decades of "talkie" films, many movie theaters presented a number of shorter items in addition to the feature film. This might include a newsreel, live-action comedy short films, documentary short films, musical short films, or cartoon shorts (many classic cartoons series such as the Looney Tunes and Mickey Mouse shorts were created for this purpose). Examples of this kind of programming are available on certain DVD releases of two of the most famous films starring Errol Flynn as a special feature arrangement designed to recreate that kind of filmgoing experience while the PBS series, Matinee at the Bijou, presented the equivalent content. Some theaters ran on continuous showings, where the same items would repeat throughout the day, with patrons arriving and departing at any time rather than having distinct entrance and exit cycles. Newsreels gradually became obsolete by the 1960s with the rise of television news, and most material now shown prior to a feature film is of a commercial or promotional nature (which usually include "trailers", which are advertisements for films and commercials for other consumer products or services).

A typical modern theater presents commercial advertising shorts, then movie trailers, and then the feature film. Advertised start times are usually for the entire program or session, not the feature itself;[60] thus people who want to avoid commercials and trailers would opt to enter later. This is easiest and causes the least inconvenience when it is not crowded or one is not very choosy about where one wants to sit. If one has a ticket for a specific seat (see below) one is formally assured of that, but it is still inconvenient and disturbing to find and claim it during the commercials and trailers, unless it is near an aisle. Some movie theaters have some kind of break during the presentation, particularly for very long films. There may also be a break between the introductory material and the feature. Some countries such as the Netherlands have a tradition of incorporating an intermission in regular feature presentations, though many theaters have now abandoned that tradition,[61] while in North America, this is very rare and usually limited to special circumstances involving extremely long movies. During the closing credits many people leave, but some stay until the end. Usually the lights are switched on after the credits, sometimes already during them. Some films show mid-credits scenes while the credits are rolling, which in comedy films are often bloopers and outtakes, or post-credits scenes, which typically set up the audience for a sequel.

Until the multiplex era, prior to showtime, the screen in some theaters would be covered by a curtain, in the style of a theater for a play. The curtain would be drawn for the feature. It is common practice in Australia for the curtain to cover part of the screen during advertising and trailers, then be fully drawn to reveal the full width of the screen for the main feature. Some theaters, lacking a curtain, filled the screen with slides of some form of abstract art prior to the start of the movie. Currently, in multiplexes, theater chains often feature a continuous slideshow between showings featuring a loop of movie trivia, promotional material for the theater chains (such as encouraging patrons to purchase drinks, snacks and popcorn, gift vouchers and group rates, or other foyer retail offers), or advertising for local and national businesses. Advertisements for Fandango and other convenient methods of purchasing tickets is often shown. Also prior to showing the film, reminders, in varying forms would be shown concerning theater etiquette (no smoking, no talking, no littering, removing crying babies, etc.) and in recent years, added reminders to silence mobile phones as well as warning concerning movie piracy with camcorders ("camming").

Some well-equipped theaters have "interlock" projectors which allow two or more projectors and sound units to be run in unison by connecting them electronically or mechanically. This set up can be used to project two prints in sync (for dual-projector 3-D) or to "interlock" one or more sound tracks to a single film. Sound interlocks were used for stereophonic sound systems before the advent of magnetic film prints.[62] Fantasound (developed by RCA in 1940 for Disney's Fantasia) was an early interlock system. Likewise, early stereophonic films such as This Is Cinerama and House of Wax utilized a separate, magnetic oxide-coated film to reproduce up to six or more tracks of stereophonic sound. Datasat Digital Entertainment, purchaser of DTS's cinema division in May 2008, uses a time code printed on and read off of the film to synchronize with a CD-ROM in the sound track, allowing multi-channel soundtracks or foreign language tracks. This is not considered a projector interlock, however.

This practice is most common with blockbuster movies. Muvico Theaters, Regal Cinemas, Pacific Theatres and AMC Theatres are some theaters that interlock films.[63]

Live broadcasting to movie theaters

[edit]Sometimes movie theaters provide digital projection of a live broadcast of an opera, concert, or other performance or event. For example, there are regular live broadcasts to movie theaters of Metropolitan Opera performances, with additionally limited repeat showings. Admission prices are often more than twice the regular movie theater admission prices.

Accessibility

[edit]Several accessibility features can be integrated into a movie theater.

Alternate audio

[edit]A Hearing Impaired (HI) audio track is designed for people who are hearing-impaired to better hear dialog. Audio description is narration for people who are blind or visually impaired.[64] Moviegoers can wear headphones which play one of these alternate audio tracks synchronized with the film.[64] In digital cinema, Hearing Impaired audio is stored in the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) on Sound Track channel 7, and audio description is stored as "Visually Impaired-Native" (VI-N) audio on Sound Track channel 8.[59]

Sign Language Video

[edit]Sign language can be displayed on a second screen device synchronized with the film.[64] In Brazil, Libras accessibility requirements mandate availability of Brazilian Sign Language for films shown in Brazilian movie theaters.[65] This video is stored in the DCP as a Sign Language Video track on Sound Track channel 15.[66]

Pricing and admission

[edit]

In order to obtain admission to a movie theater, the prospective theater-goer must usually purchase a ticket from the box office, which may be for an arbitrary seat ("open" or "free" seating, first-come, first-served) or for a specific one (allocated seating).[67] As of 2015, some theaters sell tickets online or at automated kiosks in the theater lobby. Movie theaters in North America generally have open seating. Cinemas in Europe can have free seating or numbered seating. Some theaters in Mexico offer numbered seating, in particular, Cinepolis VIP. In the case of numbered seating systems the attendee can often pick seats from a video screen. Sometimes the attendee cannot see the screen and has to make a choice based on a verbal description of the still available seats. In the case of free seats, already seated customers may be asked by staff to move one or more places for the benefit of an arriving couple or group wanting to sit together.[citation needed]

For 2013, the average price for a movie ticket in the United States was $8.13.[68] The price of a ticket may be discounted during off-peak times e.g. for matinees, and higher at busy times, typically evenings and weekends. In Australia, Canada and New Zealand, when this practice is used, it is traditional to offer the lower prices for Tuesday for all showings, one of the slowest days of the week in the movie theater business, which has led to the nickname "cheap Tuesday".[69] Sometimes tickets are cheaper on Monday, or on Sunday morning. Almost all movie theaters employ economic price discrimination: tickets for youth, students, and seniors are typically cheaper. Large theater chains, such as AMC Theatres, also own smaller theaters that show "second runs" of popular films, at reduced ticket prices. Movie theaters in India and other developing countries employ price discrimination in seating arrangement: seats closer to the screen cost less, while the ones farthest from the screen cost more. Movie theatres in India are also practicing safety guidelines and precautions after 2020.[clarification needed]

In the United States, many movie theater chains sell discounted passes, which can be exchanged for tickets to regular showings. Some passes provide substantial discounts from the price of regular admission, especially if they carry restrictions. Common restrictions include a waiting period after a movie's release before the pass can be exchanged for a ticket or specific theaters where a pass is ineligible for admission.

Some movie theaters and chains sell monthly passes for unlimited entrance to regular showings. Cinemas in Thailand have a restriction of one viewing per movie. The increasing number of 3D movies, for which an additional fee is required, somewhat undermines the concept of unlimited entrance to regular showings, in particular if no 2D version is screened, except in the cases where 3D is included. Some adult theaters sell a day pass, either as standard ticket, or as an option that costs a little more than a single admission. Also for some film festivals, a pass is sold for unlimited entrance. Discount theaters show films at a greatly discounted rate, however, the films shown are generally films that have already run for many weeks at regular theaters and thus are no longer a major draw, or films which flopped at the box office and thus have already been removed from showings at major theaters in order to free up screens for films that are a better box office draw.[citation needed]

Luxury screens

[edit]

Some cinemas in city centers offer luxury seating with services like complimentary refills of soft drinks and popcorn, a bar serving beer, wine and liquor, reclining leather seats and service bells.[71] Cinemas must have a liquor license to serve alcohol.[72] The Vue Cinema and CGV Cinema chain is a good example of a large-scale offering of such a service, called "Gold Class" and similarly, ODEON, Britain's largest cinema chain, and 21 Cineplex, Indonesia's largest cinema chain, have gallery areas in some of their bigger cinemas where there is a separate foyer area with a bar and unlimited snacks.[73][74]

Age restrictions

[edit]

Admission to a movie may also be restricted by a motion picture rating system, typically due to depictions of sex, nudity or graphic violence. According to such systems, children or teenagers below a certain age may be forbidden access to theaters showing certain movies, or only admitted when accompanied by a parent or other adult. In some jurisdictions, a rating may legally impose these age restrictions on movie theaters. Where movie theaters do not have this legal obligation, they may enforce restrictions on their own. Accordingly, a movie theater may either not be allowed to program an unrated film, or voluntarily refrain from that.

Revenue

[edit]Movie studios/film distributors in the US traditionally drive hard bargains entitling them to as much as 100% of the gross ticket revenue during the first weeks (and then the balance changes in 10% increments in favor of exhibitors at intervals that vary from film to film).[75] Film exhibition has seen a rise in its development with video consolidation as well as DVD sales, which over the past two decades is the biggest earner in revenue. According to The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry, Philip Drake states that box office takings currently account for less than a quarter of total revenues and have become increasingly "front loaded", earning the majority of receipts in the opening two weeks of exhibition, meaning that films need to make an almost instant impact in order to avoid being dropped from screens by exhibitors. Essentially, if the film does not succeed in the first few weeks of its inception, it will most likely fail in its attempt to gain a sustainable amount of revenue and thus being taken out from movie theaters. Furthermore, higher-budget films on the "opening weekend", or the three days, Friday to Sunday, can signify how much revenue it will bring in, not only to America, but as well as overseas. It may also determine the price in distribution windows through home video and television.[76]

In Canada, the total operating revenue in the movie theater industry was $1.7 billion in 2012, an 8.4% increase from 2010. This increase was mainly the result of growth in box office and concession revenue. Combined, these accounted for 91.9% of total industry operating revenue.[77] In the US, the "...number of tickets sold fell nearly 11% between 2004 and 2013, according to the report, while box office revenue increased 17%" due to increased ticket prices.[78]

New forms of competition

[edit]One reason for the decline in ticket sales in the 2000s is that "home-entertainment options [are] improving all the time— whether streamed movies and television, video games, or mobile apps—and studios releasing fewer movies", which means that "people are less likely to head to their local multiplex".[78] This decline is not something that is recent. It has been observed since the 1950s when television became widespread among working-class homes. As the years went on, home media became more popular, and the decline continued. This decline continues until this day.[79] A Pew Media survey from 2006 found that the relationship between movies watched at home versus at the movie theater was in a five to one ratio and 75% of respondents said their preferred way of watching a movie was at home, versus 21% who said they preferred to go to a theater.[80] In 2014, it was reported that the practice of releasing a film in theaters and via on-demand streaming on the same day (for selected films) and the rise in popularity of the Netflix streaming service has led to concerns in the movie theater industry.[81] Another source of competition is television, which has "...stolen a lot of cinema's best tricks – like good production values and top tier actors – and brought them into people's living rooms".[81] Since the 2010s, one of the increasing sources of competition for movie theaters is the increasing ownership by people of home theater systems which can display high-resolution Blu-ray disks of movies on large, widescreen flat-screen TVs,[81] with 5.1 surround sound and a powerful subwoofer for low-pitched sounds.

Ticket price uniformity

[edit]

The relatively strong uniformity of movie ticket prices, particularly in the U.S., is a common economics puzzle, because conventional supply and demand theory would suggest higher prices for more popular and more expensive movies, and lower prices for an unpopular "bomb" or for a documentary with less audience appeal.[82] Unlike seemingly similar forms of entertainment such as rock concerts, in which a popular performer's tickets cost much more than an unpopular performer's tickets, the demand for movies is very difficult to predict ahead of time. Indeed, some films with major stars, such as Gigli (which starred the then-supercouple of Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez), have turned out to be box-office bombs, while low-budget films with unknown actors have become smash hits (e.g., The Blair Witch Project). The demand for films is usually determined from ticket sale statistics after the movie is already out. Uniform pricing is therefore a strategy to cope with unpredictable demand. Historical and cultural factors are sometimes also cited.[83]

Ticket check

[edit]In some movie theater complexes, the theaters are arranged such that tickets are checked at the entrance into the entire plaza, rather than before each theater. At a theater with a sold-out show there is often an additional ticket check, to make sure that everybody with a ticket for that show can find a seat. The lobby may be before or after the ticket check.

Controversies

[edit]

- Advertising: Some moviegoers complain about commercial advertising shorts played before films, arguing that their absence used to be one of the main advantages of going to a movie theater. Other critics such as Roger Ebert have expressed concerns that these advertisements, plus an excessive number of movie trailers, could lead to pressure to restrict the preferred length of the feature films themselves to facilitate playing schedules. So far, the theater companies have typically been highly resistant to these complaints, citing the need for the supplementary income. Some chains like Famous Players and AMC Theatres have compromised with the commercials restricted to being shown before the scheduled start time for the trailers and the feature film. Individual theaters within a chain also sometimes adopt this policy.[84]

- Loudness: Another major recent concern is that the dramatic improvements in stereo sound systems and in subwoofer systems have led to cinemas playing the soundtracks of films at unacceptably high volume levels. Usually, the trailers are presented at a very high sound level, presumably to overcome the sounds of a busy crowd. The sound is not adjusted downward for a sparsely occupied theater. Volume is normally adjusted based on the projectionist's judgment of a high or low attendance. The film is usually shown at a lower volume level than the trailers. In response to audience complaints, a manager at a Cinemark theater in California explained that the studios set trailer sound levels, not the theater.[citation needed]

- Copyright piracy: In recent years, cinemas have started to show warnings before the movie starts against using cameras and camcorders during the movie (camming). Some patrons record the movie in order to sell "bootleg" copies on the black market. These warnings threaten customers with being removed from the cinema and arrested by the police.[citation needed] Some theaters (including those with IMAX stadiums) have dogs at the doors to sniff recording smugglers. At particularly anticipated showings, theaters may employ night vision equipment to detect a working camera during a screening. In some jurisdictions this is illegal unless the practice has been announced to the public in advance.[85]

- Crowd control: As movie theaters have grown into multiplexes and megaplexes, crowd control has become a major concern. An overcrowded megaplex can be rather unpleasant, and in an emergency can be extremely dangerous (indeed, "shouting fire in a crowded theater" is the standard example of the limits to free speech, because it could cause a deadly panic). Therefore, all major theater chains have implemented crowd control measures. The most well-known measure is the ubiquitous holdout line, which prevents ticket holders for the next showing of that weekend's most popular movie from entering the building until their particular auditorium has been cleared out and cleaned. Since the 1980s, some theater chains (especially AMC Theatres) have developed a policy of co-locating their theaters in shopping centers (as opposed to the old practice of building stand-alone theaters).[86] In some cases, lobbies and corridors cannot hold as many people as the auditoriums, thus making holdout lines necessary. In turn, ticket holders may be enticed to shop or eat while stuck outside in the holdout line. However, given the fact that rent is based on floor area, the practice of having a smaller lobby is somewhat understandable.[87]

- Refunds: Most cinema companies issue refunds if there is a technical fault such as a power outage that stops people from seeing a movie. Refunds may be offered during the initial 30 minutes of the screening. The New York Times reported that some audience members walked out of Terrence Malick's film Tree of Life and asked for refunds.[88] At AMC theaters, "...patrons who sat through the entire film and then decided they wanted their money back were out of luck, as AMC's policy is to only offer refunds 30 minutes into a screening. The same goes for Landmark, an independent movie chain... whose policy states, 'If a film is not what is expected… and the feature is viewed less than 30 minutes a refund can be processed for you at the box office.'"[88]

- Snack prices: The price of soft drinks and candy at theaters is typically significantly higher than the cost of those items at any other place. Popcorn prices can also be exorbitant. It has been "...estimated that movie theaters make an 85% profit at the concessions stand on overpriced soda, candy, nachos, hot dogs and, of course, popcorn. Movie-theater popcorn has been called one of America's biggest rip-offs, with a retail price of nine times what it costs to make."[89]

Cinema and movie theater chains

[edit]

In Africa, Ster-Kinekor has the largest market share in South Africa. Nu Metro Cinemas is another cinema chain in South Africa.

In North America, the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO) is the largest exhibition trade organization in the world. According to their figures, the top four chains represent almost half of the theater screens in North America. In Canada, Cineplex Cinemas is by far the largest player with 161 locations and 1,635 screens.

In the United States, the studios once controlled many theaters, but after the appearance of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Congress passed the Neely Anti-Block Booking Act, which eventually broke the link between the studios and the theaters. Now, the top three chains in the U.S. are Regal Cinemas, AMC Theatres and Cinemark Theatres. In 1995, Carmike was the largest chain in the United States- now, the major chains include AMC Theatres – 5,206 screens in 346 theaters,[90] Cinemark Theatres – 4,457 screens in 334 theaters,[91] Landmark Theatres – 220 screens in 54 theaters,[92] Marcus Theatres – 681 screens in 53 theaters.[93] National Amusements – 409 screens in 32 theaters[93] and Regal Cinemas – 7,334 screens in 588 theaters.[94] In 2015 the United States had a total of 40,547 screens.[95] In Mexico, the major chains are Cinépolis and Cinemex.

In South America, Argentine chains include Hoyts, Village Cinemas, Cinemark and Showcase Cinemas. Brazilian chains include Cinemark and Moviecom. Chilean chains include Hoyts and Cinemark. Colombian, Costa Rican, Panamanian and Peruvian chains include Cinemark and Cinépolis.

In Asia, Wanda Cinemas is the largest exhibitor in China, with 2,700 screens in 311 theaters[96] and with 18% of the screens in the country;[97] another major Chinese chain is UA Cinemas. China had a total of 31,627 screens in 2015 and is expected to have almost 40,000 in 2016.[95] Hong Kong has AMC Theatres. South Korea's CJ CGV also has branches in China, Indonesia, Myanmar, Turkey, Vietnam, and the United States. In India, PVR Cinemas is a leading cinema operating a chain of 500 screens and CineMAX and INOX are both multiplex chains. These theatres practice safety guidelines in each cinema halls. Indonesia has the 21 Cineplex and Cinemaxx (as of 2019, renamed as Cinépolis) chain. A major Israel theater is Cinema City International. Japanese chains include Toho and Shochiku.

Europe is served by AMC, Cineworld, Vue and Odeon.

In Oceania (particularly Australia), large chains include Event Cinemas, Village Cinemas, Hoyts Cinemas and Palace Cinemas.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Movie theater definition and meaning – Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "cinema – Definition of cinema". Oxford Dictionaries – English. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "cinema hall Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Originally spelled theatre and teatre (c. 1380), from around 1550 to 1700 or later, the most common spelling was theater. Between 1720 and 1750, theater was dropped in British English but was either retained or revived in American English (Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition, 2009, CD-ROM: ISBN 9780199563838). Recent dictionaries of American English list theatre as a less common variant, e.g., Random House Webster's College Dictionary (1991); The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, 4th edition (2006); New Oxford American Dictionary, third edition (2010); Merriam-Webster Dictionary (2011) Archived 18 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Merriam-Webster: "kinema" — British variant of cinema Archived 9 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Kinema – a journal for film and audiovisual media Archived 10 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ The Kinema in the Woods Archived 15 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine—name of cinema in Woodhall Spa Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "movie | Etymology, origin and meaning of movie by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ "theatre | Search Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Heard, Mervyn. PHANTASMAGORIA: The Secret History of the Magic Lantern. The Projection Box, 2006

- ^ The Magazine of Science, and Schools of Art – Vol. IV. 1843. p. 410. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ Allgemeine Theaterzeitung und Originalblatt für Kunst, Literatur, und geselliges Leben (in German). im Bureau der Theaterzeitung. 1847. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Rossell, Deac. "The Exhibition of Moving Pictures before 1896". Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "ANNO, Die Gegenwart. Politisch-literarisches Tagblatt, 1847-01-18, Seite 4". anno.onb.ac.at. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "ANNO, Österreichisches Morgenblatt; Zeitschrift für Vaterland, Natur und Leben, 1847-02-03, Seite 2". anno.onb.ac.at. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Le Théâtre optique". Archived from the original on 11 November 2008.

- ^ Myrent, Glenn (1989). "Emile Reynaud: First Motion Picture Cartoonist". Film History. 3 (3): 191–202. JSTOR 3814977.

- ^ The machines were modified so that they did not operate by nickel slot. According to Hendricks (1966), in each row "attendants switched the instruments on and off for customers who had paid their twenty-five cents" (p. 13). For more on the Hollands, see Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895–1939 (Montreal and Kingston, Canada; London; and Buffalo, New York: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1978), pp. 6–7. Morris states that Edison wholesaled the Kinetoscope at $200 per machine; in fact, as described below, $250 seems to have been the most common figure at first.

- ^ Streible, Dan (11 April 2008). Fight Pictures: A History of Boxing and Early Cinema. University of California Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780520940581. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "BERLIN Tivoli". www.allekinos.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "Who's Who of Victorian Cinema". www.victorian-cinema.net. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.

- ^ "World's oldest cinema to reopen in France's La Ciotat". France 24. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Aniche – le Jacques Tati". De la suite dans les images (in French). 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ Dubrulle, Benjamin (26 January 2020). "On vous refait le film de l'Idéal-cinéma Jacques-Tati d'Aniche". La Voix du Nord (in French). Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Guinness". Korsør Biograf Teater (in Danish). Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Nat Taylor | Historica – Dominion". Historica. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ Marich, Robert (2013) Marketing To Moviegoers: Third Edition (2013), SIU Press books, p.295

- ^ "Welcome to the Crest Theatre". Thecrest.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Open air cinemas". Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "You Can Watch Movies in Bed at This Theater in Switzerland". Travel + Leisure.

- ^ "9 Movie theaters with bed seats around the world – Movies In Theater". 27 December 2019.

- ^ "We visited The Bed Cinema by Omazz and absolutely loved it". 8 December 2020.

- ^ "Movie Theater With Beds Reinvents The Movie Experience". 4 December 2021.

- ^ "Outdoor pop-up theater featuring actual beds coming to Houston". ABC13 Houston. 25 February 2020.

- ^ Han-na, Park (7 September 2022). "Movie theaters offer a new experience". The Korea Herald.

- ^ "Bed Cinema – San Francisco's Most Comfortable Cinema". explorehidden.com.

- ^ "The Bed Cinema". Time Out Los Angeles. 3 April 2019.

- ^ Gunzberg, M.L. (1953). "What is Natural Vision?", New Screen Techniques. 55–59.

- ^ "Just Like 1927." BoxOffice 7 February 1953: 12.

- ^ Walters, Ben. "The Great Leap Forward." Sight & Sound, 19.3. (2009) pp. 38–41.

- ^ "Je eigen 3D-bril". Pathe.nl. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "IMAX". National Science and Media Museum. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Inside Darling Harbour iMax Theatre – Sydney – Australia". YouTube. 17 May 2016.

- ^ "IMAX to be demolished, reborn as the Ribbon". 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Maintaining The IMAX Experience, From Museum To Multiplex". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Verrier, Richard (15 April 2015). "Imax premieres new laser system at TCL Chinese Theatre in Hollywood". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ "Bow Tie to Open New PLF Theatre". Digital Cinema Report. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "INOX launches Goa's Largest Cinema Screen BIGPIX at Old GMC Panaji". Adgully. 17 December 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Riccioli, Jim. "Four big reasons why today's experience is so much better in Marcus Theatre's local cinemas than years ago". Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ^ jimjin (4 June 2021). "Get the popcorn, cinema opening in Altona North". Maribyrnong & Hobsons Bay. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ "These are 19 of the most unusual Southern California movie theaters". Pasadena Star News. 12 March 2018. Archived from the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Wilson, Christie (18 June 2010). "Audiences prepare for splash of this Titan". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ a b "How Premium Large Format Auditoriums Are Helping Welcome Audiences Back to the Movies". Boxoffice. 29 July 2021. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Going Big: More and more circuits invest in Premium Large Format brands". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (12 April 2014). "Battle for the Bigger Screen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Dolby Launches Dolby Cinema". Digital Cinema Report. 3 December 2014. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ "About Us". CGV Cinemas. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ "Recommended Guidelines for Digital Cinema Source and DCP Content Delivery" (PDF). Deluxe Technicolor Digital Cinema. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ a b D-Cinema Packaging — SMPTE DCP Bv2.1 Application Profile. The Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. 18 May 2020. doi:10.5594/SMPTE.RDD52.2020. ISBN 978-1-68303-222-9. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "The love and loathing of cinema ads" Archived 14 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News website, 23 February 2005

- ^ "Boom Chicago : Real-Amsterdam : Tuschinksi Reopens". Archived from the original on 20 April 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Boorstin, Jon (25 March 2016). "On Its 40th Anniversary: Notes on the Making of All the President's Men". Los Angeles Review of Books. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Cover Your Eyes! How Harry Guerro Brought the Wildest Old 3-D Movies to the Quad Cinema". www.villagevoice.com. 12 October 2017. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ a b c "Accessibility & The Audio Track File". Cinepedia. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Deluxe Launches First Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) Localization Service Outside Brazil". Cision PR Newswire. Deluxe Entertainment Services Group Inc. through Cision PR Newswire. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Recommended Guidelines for Digital Cinema Source and DCP Content Delivery" (PDF). Deluxe Technicolor Digital Cinema. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "FAQs – Vue Cinemas". Vue Cinemas. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Cinema Statistics for 2013". MarketingMovies.net. Archived from the original on 30 March 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ "First the accusatory vignettes that air before the movie, and now this". Skirl – Dan Dickinson. 2 April 2004. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Fine Arts Group". Archived from the original on 20 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Surround Sound? IMAX? Chardonnay? Movie Theaters Look to Alcoholic Beverages". Wine Spectator. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "Licence types and trading hours". sitefinitycms-staging. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Swindale, Rachael (8 June 2019). "Want to save money at the movies? Here's the full picture". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Young, Graham (2 June 2018). "First look around Britain's biggest luxury cinema in Birmingham". birminghammail. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Filson, Darren; Switzer, David; Besocke, Portia (April 2005). "At The Movies: The Economics Of Exhibition Contracts". Economic Inquiry. 43 (2): 354–370. doi:10.1093/ei/cbi024.

- ^ McDonald, Paul; Wasko, Janet (2008). The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. 126.

- ^ "Statcan.gc.ca" (PDF). Statcan.gc.ca. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ^ a b Erich Schwartzel and Ben Fritz (25 March 2014). "Fewer Americans Go to the Movies". WSJ. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Spraos, John (2013). The Decline of the Cinema: An Economist's Report. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-72675-7.[page needed]

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c "Could Netflix Kill the Movie Theater Industry?". Screen Rant. 5 October 2014. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "·" (PDF). stanford.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ McKenzie, Richard B. (2008). Why Popcorn Costs So Much at the Movies: And Other Pricing Puzzles. pp. 166–174. ISBN 978-0-387-76999-8.

- ^ "Movie theater". www.drhdmi.eu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "ILLEGAL RECORDINGIN CINEMAS" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Calimbahin, Samantha (22 February 2017). "Next Tenant for The Shops at Clearfork is AMC Theatres". Fort Worth Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ FADEN, ERIC S. (2001). "Crowd Control: Early Cinema, Sound, and Digital Images". Journal of Film and Video. 53 (2/3): 93–106. ISSN 0742-4671. JSTOR 20688359.

- ^ a b "'Tree of Life' walk-outs - EW.com". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Tuttle, Brad (19 March 2012). "Why Does Movie-Theater Popcorn, Soda, Candy Cost So Much? - TIME.com". TIME.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ "Learn about the " IT" Factor at AMC". AMC Entertainment. 16 March 2009. Archived from the original on 9 September 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "About Us". Cinemark. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "About Landmark Theatres". Landmarktheatres.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Top Ten U.S. & Canadian Circuits". Natoonline.org. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ^ "Regal Movie Theaters | About Us". Regmovies.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ a b Rahman, Abid (12 June 2016). "Shanghai Film Festival: China to Top U.S. Screen Total by 2017, Says Wanda Cinema Chief". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 13 June 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (22 June 2016). "Wanda Opens Asia's First Dolby Cinema Theater". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (15 June 2016). "Is 'Warcraft's Outsized China Box Office A Game-Changer For Hollywood?". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cinemas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cinemas at Wikimedia Commons- Movie theaters early users of air conditioning – Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois newspaper)